In the movie that catapulted him to big-screen stardom, "White Men Can't Jump" (1992), Woody Harrelson showed he had the imaginative zing to take audiences to unexpected places and the emotional depth to satisfy them once they got there. Playing Woody Boyd, the transcendently naive bartender on TV's "Cheers," had made him famous; it also threatened to typecast him. (Sharing the same first name with his beloved fictional alter ego didn't help.) Even in the advance press coverage for "White Men," journalists depicted the playground basketball whiz Harrelson portrayed for writer-director Ron Shelton ("Bull Durham") as a twist on his lovable "Cheers" hick.

Yet as the hoops hustler in "White Men," Harrelson embodied dimensions he'd never suggested before. Billy was a romantic idealist with mischievous impulses. When he teamed up with Wesley Snipes' streetwise showboat for playground cons and tournament action, he brought a hopped-up, homegrown, improbably aggressive kind of Zen to their synergy. At his peak, he was able to get into a "zone" -- a psychic state in which he couldn't miss -- and to put Snipes in one, too. Their surprising push-pull chemistry helped make the film a smash.

Snipes, not Harrelson, became the breakaway box-office phenomenon, cashing in with a series of now-forgotten action films like "Passenger 57," "Demolition Man" and "Drop Zone." Most of the time, Harrelson has gone the opposite route, working on one controversial or ambitious production after another, from Oliver Stone's "Natural Born Killers" (1994) and Milos Forman's "The People Vs. Larry Flynt" (1996) to Terrence Malick's "The Thin Red Line" (1998). Often, as in Stephen Frears' neo-western "The Hi-Lo Country" (also 1998), he's the best part of a movie. Yet despite an Oscar nomination for his sly, empathic portrayal of Flynt and the respect he has won for taking small roles in worthy films like "Welcome to Sarajevo" (1997), Harrelson hasn't gotten his full due as an actor.

His off-screen life too often overshadows his on-screen accomplishment. Coverage has never ceased about the father he barely knew growing up, a professional gambler and convicted hit man currently serving two life sentences for the 1979 murder of a federal judge. (Harrelson supports his father's appeal for a retrial.) And Harrelson has been an outspoken activist on diverse causes -- from opposition to the Gulf War to legalization of marijuana. He even climbed the Golden Gate Bridge to protest the devastation of California's redwoods.

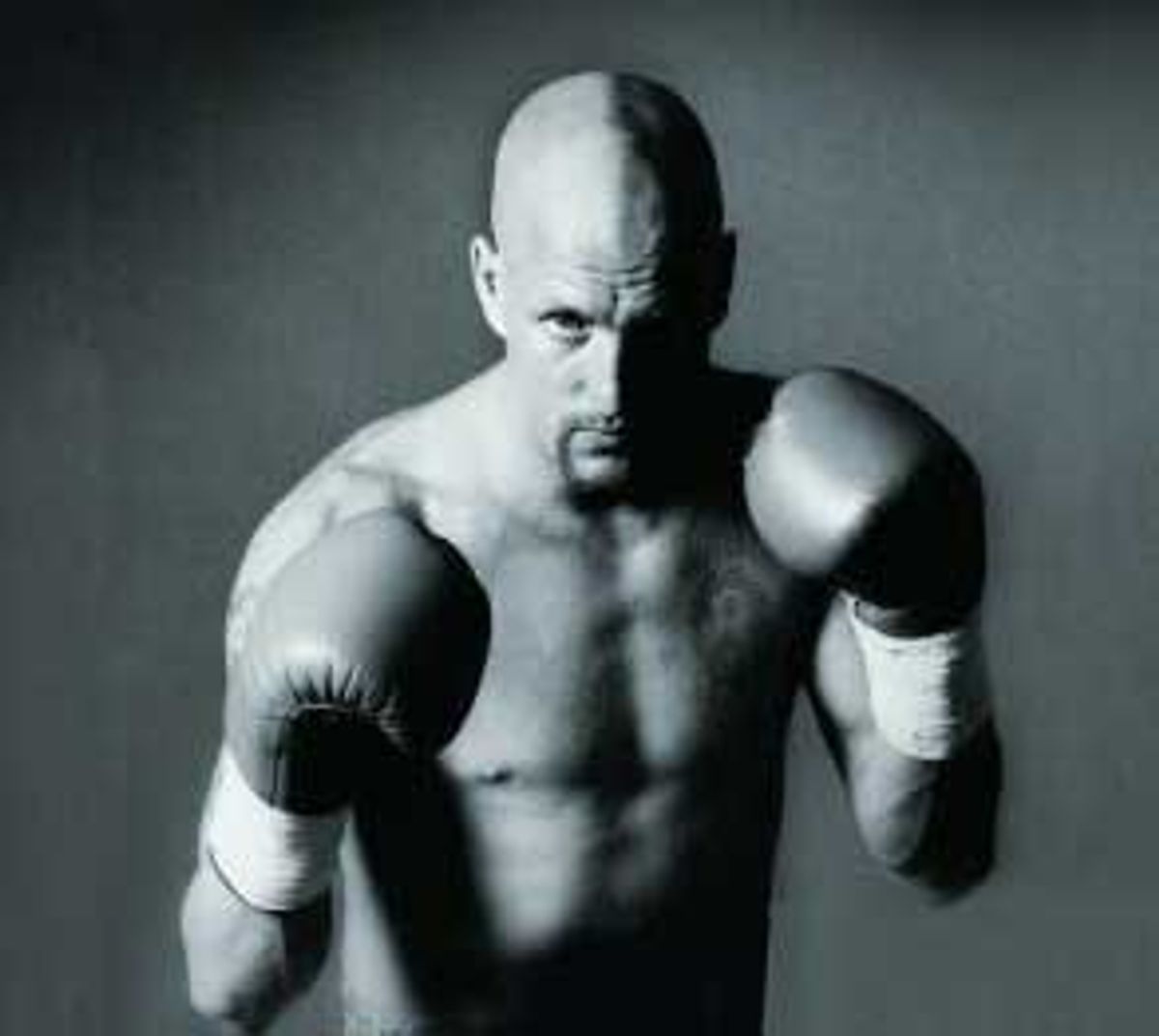

Harrelson's narration of the pro-marijuana documentary "Grass" has received more publicity than his reunion with Shelton in last winter's "Play It to the Bone," a juicy piece of vernacular poetry about the life and art of boxers. After an early screening in Hollywood, director Roger Spottiswoode ("Tomorrow Never Dies") told me he thought it was Shelton's best movie and potentially his biggest hit; the executives at Touchstone Pictures agreed, positioning it as an Oscar picture.

But the strategy backfired: "Play It to the Bone" tanked commercially and critically. Maybe with the Oscar-season pressure off, audiences will discover the rambling pleasures of a film that joins the lowdown charms of road movies to a boxing sequence unlike any other in its mix of ferocity and emotion. Harrelson plays Vince Boudreau, a womanizing Jesus freak who could have been a contender, and can get one more shot at a title if he defeats his best friend (Antonio Banderas) -- who also happens to be the current lover of his ex-girlfriend (Lolita Davidovich). One associates this kind of visceral, askew role with Sean Penn. Harrelson embraces this daunting challenge with a comic sympathy so intense that you can't imagine anyone else playing Vince Boudreau.

With "Play It to the Bone" now out on home video and DVD, Harrelson stole an hour to talk with me about his fondness for that movie. Although the actor has no film in the works, his schedule hasn't been easy: Early last week he was in Denver, attending his father's hearing for a new trial. Later in the week he was in Winnipeg, Canada, conferring on the establishment of the first nonwood paper mill in North America. He called me from Winnipeg by cellphone. Whenever he started to talk about the ecological necessity of finding substitutes for wood pulp (including industrial hemp), he would catch himself and say, "I don't want to get into my preaching mode."

What he did want to talk about is why he has done some of his best acting for Shelton. "I really do feel like we have a rapport," he said. "He's like the best example of a benign dictator. He's open and flexible, and if I give him 10 ideas he'll tell me nine of them stink -- and that's great. I love his movies because I think they have qualities of heart and humanity and are funny at the same time. Which is the best way for movies to be -- you don't want them to be hitting you over the head with ideas and concepts. And Ron always comes up with interesting characters who create a combustion when you put them together."

But what drew him to Vince, a gnarly eccentric who hasn't been a force in boxing for years? "I always connect to something about the heart of a character, and I love the fact that he's a guy who had more than one shot and never got to be a champion." Does Harrelson think that being a "loser" has more to do with the common man than being a "winner"? "That's definitely part of it. All I know is, if Vince were successful he wouldn't be nearly as interesting for me. I like the fact that he and Antonio take this journey, and it's all in one day, and at the beginning of the day they don't know they're going to have this opportunity to box in Las Vegas, which is ultimately the opportunity to be contenders again. And I liked Vince's passion for religion as well as for boxing -- this was a part unlike any other that I'd read."

Harrelson has his own primal connection to religion. His mother, who divorced his dad and brought up him and his two brothers alone, was deeply religious and saw to it that he never skipped church. "I grew up very religious myself," says Harrelson, "so it was important to me that Vince's religion be based in reality and also have some potency." Harrelson went to Hanover College in Hanover, Ind., on a Presbyterian scholarship; Shelton graduated from Westmont, an evangelical Baptist college in Santa Barbara, Calif. Harrelson says, "Things shifted in the script as Ron and I were discussing it from the first draft to what we ended up with." Such as? "Some of the sensibilities that the character was after, or that we were after for the character. For example, when Vince says that Jesus was a rebel and that if he came back today he wouldn't just be throwing the moneylenders out of the temple, he'd be torching the Vatican, you hope that will be funny, because it's so extreme, but to a lot of people it's not funny at all."

What's hilarious about Vince is his combination of irreverence and utter sureness in his vision. One of the film's funniest touches is that the savior Vince sees in the flesh is a white-skinned, white-robed, long-haired Christ, straight out of a Christmas card or a Hollywood Bible epic. Yet we never doubt for a second that Vince is a true believer. "Speaking of belief," Harrelson says, "this may be hard to believe. But when I was younger I actually gave two sermons -- one when I was 17, one when I was maybe 19. And both of them had to do with the same subject: faith. And that is what we are talking about: believing. I consider it more important than anything, because when you believe in something, that's when the forces of the universe seem to line up behind you. But the believing comes first. That's a very important part of what Vince is all about."

And isn't believing an important part of what Woody Harrelson is about? "That's true! I believe in a lot of things that people may not see the full merits of, like industrial hemp. I just see the economy destroying the ecology as well as being unsustainable." At that point his cellphone broke up, and when we reconnected Harrelson said, "That's good -- I was going into my preaching phase, and now I'm going to get out of that."

In both his movies with Shelton, Harrelson has shown crack timing with his costars. "That's something that develops in the conversations we have together. The relationship is there on the page; there are obviously parameters, but we get a feel for how we interact." Harrelson acted with Snipes before and after "White Men," and they remain good friends. But only in Shelton's basketball movie does Harrelson think they had a director who let them display the "nature of our relationship -- it was a heightened version of the way we interact."

In the miserable 1995 action spectacle "Money Train," Harrelson says, he and Snipes "were just cogs in a wheel, literally and figuratively." The talented Joseph Ruben ("The Stepfather") directed this fiasco; he failed to strike the "Wesley and Woody" spark promised in the ads. "Too much money, too much train" -- that's how Harrelson sums up "Money Train." But in "White Men Can't Jump," Harrelson says, "Wesley and I did a lot of improvising and that's kind of who we are, at least in relation to each other. I talked to Wes a week ago; he had seen 'White Men' again the night before and he was saying we got some funny stuff there. I really would like to do something else with Wesley."

As for Banderas in "Play It to the Bone," who has the role of Cesar, a Madrid boxer who ends up in Los Angeles by way of Philadelphia: "I never met anyone so professional who could at the same time keep it really loose and fly with things. I guess you could say that he has all the qualities that a good actor can have, in that he can be spontaneous yet still prepare like you rarely see anyone prepare. He is still self-conscious about his accent -- I don't think he should be -- and he would study his lines by recording them on tape and listening to them through the night. But he is a consummate pro and just a good guy."

Harrelson doesn't share Vince's horror at Cesar's experiments with homosexuality. But he turns Vince's feelings of disbelief and aversion into a comic primal scene, epitomized in the way Vince screams out, "No details!" Harrelson says, "That was definitely one of my favorite scenes. I don't know what I was drawing on because I don't feel that way in life, but it's definitely the way Vince would react -- he would not take that very well. And that to me is another example of the way Ron can work really important themes into what is essentially a comedy -- although I should say Ron was not liking it when I was just calling it a comedy. I think the whole issue of homosexuality is extremely important, and when Vinnie goes from being really not cool with it to, at the end, being cool with it, I think he may bring someone watching it to a better place, too. In that way, it's like 'White Men Can't Jump' -- there was a real powerful message there about the relationship between black and white, and you never saw it coming at all."

That casual profundity is also a tribute to Harrelson's skill at embodying characters without condescension and instinctively shaping their trajectories. Whether as a swashbuckling journalist in "Welcome to Sarajevo" or a cantankerous cowboy in "The Hi-Lo Country," he gradually reveals inner dimensions and tender edges to ultra-extroverted men. Nowhere is that more true than in "Play It to the Bone." But Harrelson gives much of the credit to Shelton: "There's always an arc to the character, and that first impression is important; in that first scene in 'Play It to the Bone,' where we get the phone call in the gym -- at that time I didn't know what I was doing. I feel like I may have wanted to play the comedy of it more, with me struggling for the phone with Antonio, and other choices I was making there. Ron kept urging us to make it more real; I appreciated Ron keeping me tethered to reality."

This director-conscious actor has been willing to take supporting roles for men whose track records and talent he respects. Harrelson was unnervingly nutty as the psycho soldier that Robert De Niro and Dustin Hoffman transform into a pseudo war hero in Barry Levinson's "Wag the Dog." Levinson "has this great feel for actors and for comedy," Harrelson says. "He doesn't have to say much -- and a lot of the best directors don't say much. Instead of saying, 'Do it this way,' they say a few words that trigger something in you and inspire you to do it this way. There was definitely some nervousness the first day, working with all those great people. But Levinson had this great rapport with Dustin and old Bobby D. there. They made you feel pretty comfortable. I was able to relax -- and if you don't relax, you can't act. You can come off with whatever intensity you want, but first you have to be relaxed."

Harrelson also scored in Malick's "The Thin Red Line" as a sergeant who makes the rookie mistake of pulling a grenade out by the pin and, as the character puts it, blowing up his own butt. The actor crafted it into a tragicomic cameo. Malick is not known as an actor's director, but Harrelson says, "I liked him as a person immensely; he has a tremendous spirit about him. He comes across as a bit of an idiot savant -- well, lose the idiot part, because he's brilliant, but there's definitely something of the savant about him. He's got this little-boy quality: He'll look off and see the wind blowing and the way the light is shining and say, 'Let's line up the camera here.' It's hard to pin down what genius is all about, I suspect."

Harrelson says, "When I do direct, I might get carried away with the comedy." At this point, Harrelson's directorial ambitions are centered on the stage. He's collaborating with an old friend, Frankie Hyman, on a play called "Furthest From the Sun," which Harrelson staged in L.A. in 1993, revived six years later in Minneapolis and continues to hone with an eye toward a new production. Hyman, Harrelson and another buddy of the actor's, Clint Allen, were close pals during Harrelson's early years as a New York actor; their experiences back then form the basis for "Furthest From the Sun," which Harrelson describes as "kind of a relationship play about two white guys and a black guy [Hyman is black] living together and the relationships they have with these women ... Gee whiz, I've never been able to encapsulate it into a sentence."

Harrelson sounds thrilled about acting on the stage these days, too. Last fall he appeared as Starbuck in a Broadway revival of "The Rainmaker," and though he says, "I must confess, only one time out of 10 did I think, 'Yes, that was it,'" he also calls it "a great learning experience." This fall he'll appear in a new Sam Shepard play, "The Late Henry Moss," for San Francisco's Magic Theatre, with Sean Penn, Nick Nolte, Cheech Marin and James Gammon. Shepard himself will direct.

"I was hanging out with Sean one night," Harrelson explains, "and he mentioned it to me a couple of times. He said I should look into it. I think they'd offered the part I took to Billy Bob Thornton, but Billy Bob's schedule wouldn't permit it. So I just called and it worked out. I play this character 'Taxi' -- I'm really only in the second act of a three-act play. We're all trying to figure out the circumstances of Sean's father's death. Nick and Sean play brothers; I was one of the last people their father was with. I gave him a taxi ride when he was on a fishing excursion, and I have to explain it to Sean, who is not very happy. But it's funny. It's classic Sam Shepard. Just the thought of doing a new Sam Shepard play with Sam Shepard directing is more exciting than I can tell you. Add to that this talented group of actors, and I feel lucky to be a part of it. It's going to be cool."

Shares