"The Matrix Revolutions" isn't a terrible movie, but it is a tremendous disappointment. It has great things in it: a creepy, semi-mystical subway train that takes people (or entities, or programs, or whatever) from one world to the next; a prodigiously exciting last-stand battle between humans and machines that equals any action sequence in the series. But it feels like a lot less than the sum of its parts. It will certainly be a letdown for anybody who believed, or hoped -- as I did -- that the Wachowski brothers were capable of producing an epic for the digital era, a combination of pomo philosophy and old-fashioned storytelling that could simultaneously enthrall a mass audience and question the very system of enthrallment, the society of the spectacle, that had produced it.

In fairness, I believe the Wachowskis got two-thirds of the way there, plus a little more. I'm sticking to my guns on the subject of "The Matrix Reloaded," which broadened and deepened the entire "Matrix" saga, adding new layers of political and cultural commentary while raising the action-movie stakes. Critics who didn't like it, I suspect, had their signal-to-noise ratio confused: They missed the hypermodern fashion and design sensibility of the 1999 original (and maybe the technophile, boom-market world it signified). The cumulative effect in "Reloaded" of Cornel West, that multiculti rave scene, and all those black people with dreadlocks seemed to provoke some kind of kneejerk anti-p.c. backlash. Oh, no -- an optimistic, even egalitarian social vision! Please don't serve us that with our black leather, our wraparound shades and our sci-fi apocalypse!

You might actually argue that "Reloaded" went too far and did too much, throwing so many narrative and/or thematic challenges and conundrums into the air that in this movie they come crashing to earth with a thud. Think you're going to learn something new about the Merovingian (Lambert Wilson), that aristocratic Francophone piece of software code, and about his impossibly curvaceous and possibly treacherous wife, Persephone (Monica Bellucci)? Uh, think again. (I'm not counting the info all Matrix-heads have now gleaned from the Internet, to wit, that the Merovingians were a dynasty of Frankish kings, descendants of the perhaps mythical Merowech, who ruled much of present-day France and Germany from the 5th to the 8th century A.D.)

Is some light to be shed on the cryptic encounter between Neo (Keanu Reeves) and the Architect (Helmut Bakaitis) in "Reloaded," in which it appears that, yes, Neo may be "the One," but he also may be trapped in a reiterative cycle he can't control or escape? Well, not much, frankly. Is the Architect himself a machine, a flesh-and-blood being, or something else? Hmm. What about the Oracle (still a cookie-baking black lady, but now played by Mary Alice in place of the late Gloria Foster, a transition handled about as well as it could be) -- who is she and what's her relationship to the Architect? Um, well, see ... Why exactly do Neo's powers over time, matter and space begin to assert themselves outside the Matrix? I guess, er, just because they do.

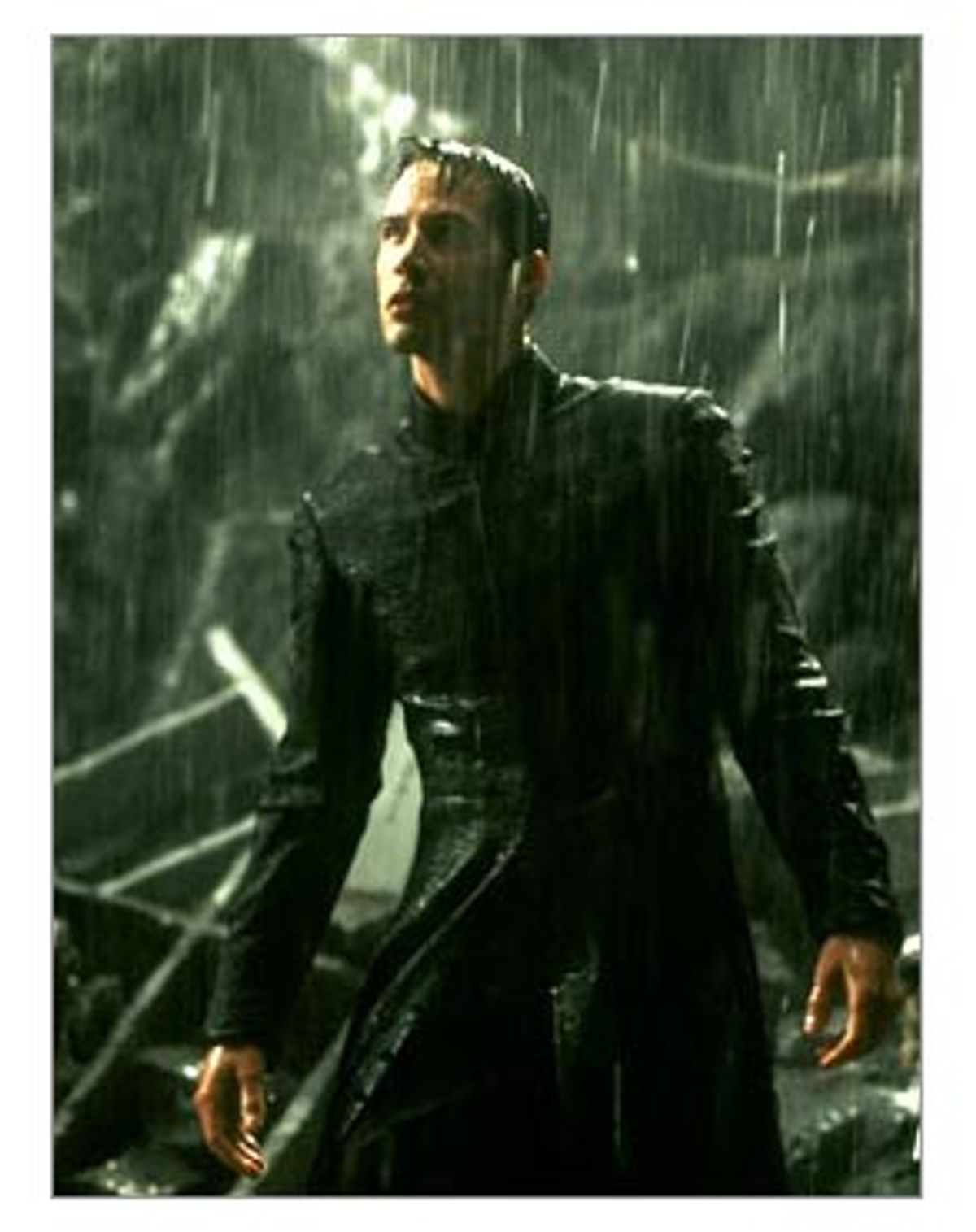

OK, in fairness, the Wachowskis do provide answers to a couple of those questions, in between the shootout scenes that seem longer and slightly more pointless than ever before. But they do so pretty much with the air of two guys desperately checking things off a laundry list. There's just too much plot to untangle, too many semi-naked girls dancing in bogus S/M outfits, too many flying kung fu moves over empty, rain-slicked streets, and that's all this ever narrower, ever more literal-minded movie can handle. "Revolutions" basically jettisons all its plot complexities as it plunges toward its final splashdown, dumping every larger philosophical or epistemological or whateverological question that's been hanging over the series. In the end, this is neither more nor less than a solid action-adventure flick (with some vague New Age ideology in the margins), maybe the third- or fourth-best one I'll see this year.

As you may recall, the subterranean human city of Zion (home to that burgeoning multiculti rave scene) will soon be under attack from 250,000 of those horrible squidlike bug-eyed robots, tunneling their way down from Earth's uninhabitable surface, where machines rule. Meanwhile, in the dream world of the Matrix, where 99 percent of humanity lives its tranquilized existence, the nefarious Agent Smith (Hugo Weaving, whose hambone acting supplies some badly needed levity) is multiplying like a virus or an unstoppable algorithm, threatening to overrun the place and turn the whole universe (both Matrix and non-) into a smirking, LBJ-era singularity.

To complicate matters further, Neo is stuck somewhere in the Matrix -- or, more accurately, in one of those interstitial, "backstage" spaces we learned about in "Reloaded" that lie in between the Matrix and the real world. (I keep being reminded of how startled I was as a child to grasp that Disneyland was full of underground tunnels and half-concealed passageways.) A dazzling early scene in which Neo wakes up in a mysterious train station and is befriended by a charming South Asian family (it's a borderline-offensive joke: they are not programmers but programs) is almost the best thing in the whole movie.

Confronted with the evidence that these software parents love their little girl and are trying to save her from what is becoming of the Matrix, Neo says, "But love is a human emotion." Sweetly, shaking his head, the girl's father says, "No. It is a word." It's just a moment of the sort of good-natured grad-school puzzler that, for better or worse, lifted the entire "Matrix" enterprise head and shoulders above its genre.

Of course, Neo's lover Trinity (Carrie-Anne Moss) and his guru Morpheus (Laurence Fishburne) must go into the Matrix, break up the Merovingian's S/M club scene with a half-comical John Woo guns-'n'-ammo showdown and force him to set Neo free. (He simpers: "It is remarkable how similar the path of love is to the path of insanity." Trinity, with many guns pressed to her head and hers pressed to his: "What's it gonna be, Merv?") Once rescued, though, Neo doesn't stay in Zion long; even as the machines are breaking through the outer walls of the city, he has to take one of the scarce human ships and set out on his lonely, heroic quest to save the world.

Neo is mostly out of the picture while Zion is fighting its apocalyptic battle against the invading calamari machines, and if that makes a certain amount of narrative sense, it's also just one of the ways this movie feels miscalculated. At no point in "Revolutions" do Neo, Trinity and Morpheus -- the trio so central to this series -- ever join forces to kick some virtual ass. In fact, Fishburne is barely a presence in this film, besides showing up before the Zion Council of Elders to issue more loony-sounding proclamations, and Moss (who plays arguably the most charismatic character of all) is only slightly more visible.

The Wachowskis undeniably have a structure at work; they're trying to resolve all the unresolvable questions of this series through a system of doubling, or echoing. If Neo is this world's savior, then Agent Smith is his opposing and equivalent force. The Oracle (with her yin-yang earrings) is in some sense paired with the Architect. The crunchy rave scene in "Reloaded" is matched with the Merovingian's overly theatrical perverts' ball, and the second film's memorable love scene between Neo and Trinity is answered by a tragic version near the end of "Revolutions." As the machines invade Zion, Neo is undertaking his own solitary voyage to the machines' home city, a phantasmagorical landscape no human has seen for centuries.

But saying that these filmmakers are ambitious, and that they're trying to do great things -- trying to manage some vast cultural-mythical core dump that encompasses the New Testament, J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, "The Wizard of Oz," contemporary critical theory, left-wing politics and "Tristan und Isolde" -- doesn't mean much of it works in the end. The best stuff in "The Matrix Revolutions," after those early, provocative train scenes, involves a bunch of characters we've basically never seen before fighting against impossible odds for the survival of the human race, while Neo wanders through his cartoony "2001"-goes-to-Mordor search for the Big Answers (which turn out to be nearly as goofy as those in Brian De Palma's ill-fated "Mission to Mars").

Neo and Agent Smith are of course heading toward a final martial-arts showdown amid Bill Pope's perpetual-gloom cinematography (which seemed so desperately contemporary four years ago), but nothing they can do, no building-site destruction, no slo-mo face pummeling, can erase the sense that the "Matrix" series has simply dragged on for too long. It would have been better left unresolved, left dangling forever over our so-called real world as a tantalizing realm of postmodern polymorphous possibilities. Now we have to live with the fact that it was never more than a cool idea for a movie.

Shares