On one level, the universe of the Matrix movies is the same as it ever was: For most viewers, most of the time, "The Matrix Reloaded" will be nothing more or less than the coolest action movie of the summer, an ultra-high-tech blend of Hollywood black magic and jaw-dropping martial arts expertise, with Keanu Reeves as the baddest Shaolin monk ever to kick ass. But on another level, the level of dense and intense geekdom -- the level of Philip K. Dick references and Jean Baudrillard quotations and the apocryphal teachings of a noted Jewish heretic prophet born in Bethlehem 2,000-odd years back -- all has changed, changed utterly.

So what do we learn in Andy and Larry Wachowski's second installment about the war between the human race and the machines that keep 99 percent of humanity imprisoned and enslaved, keep it living out "real life" in a highly sophisticated set of software programs whose simulated world strongly resembles, well, Western civilization circa right now? Of course I shouldn't tell you anything at all about what we learn, or even drop any hints -- and the Wachowskis have made that task easier, because the real answer to the question is: not all that much.

"The Matrix Reloaded" is a defiant middle-chapter movie, maybe even more so than Peter Jackson's "The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers." It begins with no prologue or back-story whatsoever and ends on a virtual cliffhanger. (If you're new to the series, take the red pill and watch the first movie first. Remember: There is no spoon.) In between -- and in between the mind-blowing action scenes and special-effects set pieces, which, if they can't possibly match the revolutionary impact of the 1999 original, outdo it in terms of sheer spectacle -- the Wachowskis give us a hell of a lot more questions than they do answers.

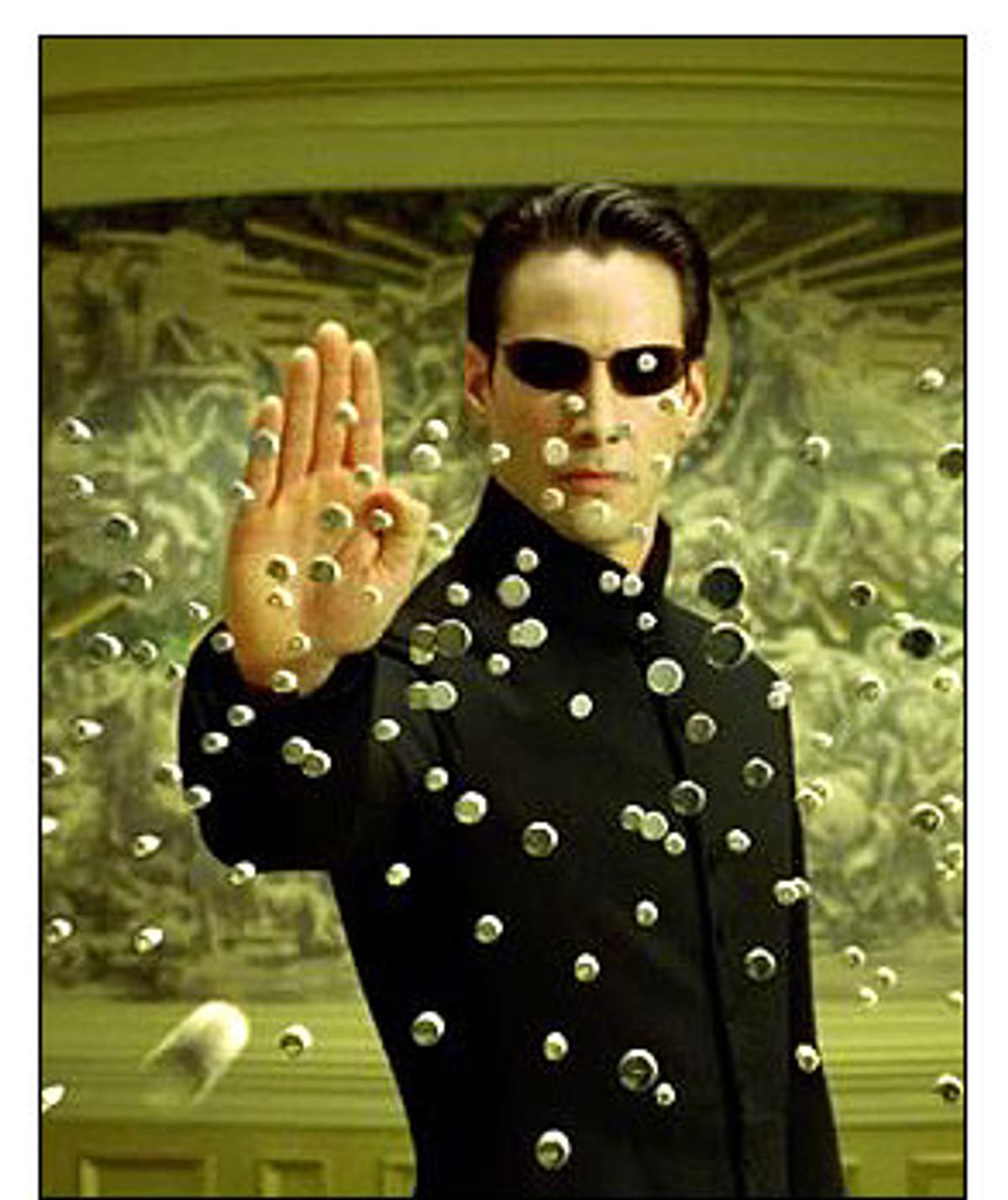

In other words, at least some fanatics will be disappointed in "The Matrix Reloaded," despite the freeway chase sequence that lasts almost a quarter of an hour, the awesome teahouse fight scene that pays homage to all the classic kung fu movies the Wachowskis have undoubtedly absorbed or the hand-to-hand combat between Neo (Keanu Reeves) and a clone army generated by the nefarious, and increasingly mysterious, Agent Smith (Hugo Weaving). On the whole, the Matrix saga seems to be moving in the direction of doubt rather than quasi-religious certainty, toward becoming a metaphysical puzzler rather than a clear-cut fable of salvation and redemption.

Maybe that's why I found "The Matrix Reloaded" so exhilarating. It's a sadder, wiser, more grown-up movie than its predecessor. It was made, one might almost say, for a sadder, wiser, more grown-up world. (Remember that in the first film Agent Smith refers to the band of renegades led by Laurence Fishburne's Morpheus as "the world's most dangerous terrorists.") More than that, it introduces a startling new sense of humanity and passion into the Matrix saga. It's not fair to suggest the Wachowskis ever seemed like cold filmmakers, exactly; their passion for moviemaking and storytelling, their desire to thrill an audience without condescending to it, were always obvious. But in "The Matrix Reloaded" they take the time to show us what Neo and his tough-babe squeeze Trinity (Carrie-Anne Moss) and über-cool guide/guru Morpheus and the rest of the human rebels battling against the technocratic enslavement of the Matrix are fighting for. It's not the awesome designer leathers and sunglasses, the Porsches and Ducati bikes; as cool as those things may seem, they exist in the Matrix, which is to say they don't really exist at all.

Early on in the film, Morpheus whips the inhabitants of Zion, the underground city where the last band of human rebels have their stronghold, into a frenzy. The agents of the Matrix have finally located Zion, and a dreadful army of 250,000 Sentinels -- those scary, dreadlocked killing machines from the first film -- is burrowing down through the earth, on its way to destroy the city and annihilate the free survivors of the human race. But Morpheus does not rouse the citizens of Zion for battle, although a final battle is close at hand. He wants them to party. The machines have been trying to kill them for years, decades, he reminds them, longer than anyone living can remember: "But we are still alive!"

What follows is a thunderously exciting all-night multicultural rave, an ecstatic dance party the likes of which I've never seen on film before -- intercut with a hot 'n' sweaty interlude between Neo and Trinity, who've been struggling to find some Q.T. together amid the impending apocalypse and hordes of strangers who want Neo to bless their babies. One of the marks of genuine genius in the Matrix films, I think, is the way the Wachowskis manage to have it both ways so much of the time: They can make a box-office-busting action spectacular that is also an explicit critique of media-age capitalism and a lefty-Christian parable. They can turn a sex scene between two movie stars with fabulous bodies into a celebration of the sheer sensuous delight we all share (or should share, anyway) just at being alive, experiencing the world with our own bodies and our own minds.

Hey, as political visions of the human future go, half-naked bodies of many races movin' and groovin' together is a hell of a lot better than most. As anarchist foremother Emma Goldman reputedly said -- and I wouldn't be at all surprised if the Wachowskis had this in mind -- "If I can't dance, I don't want to be part of your revolution."

(Actually, this oft-repeated and oft-altered line is apocryphal, as feminist scholar Alix Kates Shulman makes clear in an article on the subject. What Goldman really wrote, although less succinct, might be even better as a maxim for fighting the Matrix: "I did not believe that a Cause which stood for a beautiful ideal, for anarchism, for release and freedom from conventions and prejudice, should demand the denial of life and joy. If it meant that, I did not want it. 'I want freedom, the right to self-expression, everybody's right to beautiful, radiant things.' Anarchism meant that to me, and I would live it in spite of the whole world -- prisons, persecution, everything.")

No one who watched "The Matrix" with even 10 percent of his or her brain engaged could have missed the fact that, at least potentially, it was a social and political allegory of tremendous resonance. Predictably, the major media coverage of the film, in 1999 and subsequently, has focused on its technological marvels and understood its more radical, even dialectical dimension as some kind of smug, ironic gamesmanship. The Wachowskis' real innovations, conventional wisdom holds, came in the "Bullet Time" sequence or in their appropriation and expansion of John Woo's action-movie vocabulary. The apparently contradictory fact that this same big-budget action movie, distributed by a gigantic infotainment conglomerate, suggested that our entire culture was an illusion and that we had been hopelessly enslaved and cut off from real life by our own technology was conveniently overlooked.

In "The Matrix Reloaded," with its affectionate but faintly satirical portrait of the ruling council of Zion -- a collection of robe-wearing crones and stately older men and nattily attired people of color that reminded me of a school board meeting in Berkeley, Calif., where I grew up -- the Wachowskis come ever closer to outing themselves as lefties. OK, they're lefties with a sense of humor and a capacity for self-criticism and an intellectual bent that sometimes gets them tied in knots. But, hey, those are the best kind.

One of the most striking aspects of this film's depiction of Zion is its racial composition; more than half the population seems to be black or brown, and the community's leaders are predominantly black men. (Don't miss radical African-American scholar Cornel West, in a brief role as a member of the council! Or boxer Roy Jones Jr., as a hovercraft captain!) No one ever mentions the racial dynamics of Matrix-resistance, and it's not directly germane to the plot in any way, but it makes the standard "integration" of the science-fiction future, as pioneered by "Star Trek," look like the tokenism it really is. Inside the world of the Matrix, on the other hand -- which is to say our world -- we hardly ever see nonwhite people, except for Morpheus himself and the cryptic Oracle (the late Gloria Foster), whose Matrix identity is that of an older woman in an inner-city housing project. The "agents" of the Matrix, of course, are all white men in narrow-lapel suits with little earphones and sunglasses; they look like LBJ's Secret Service detail, with a dash of Blues Brothers.

The Wachowskis have also put relationships between their black characters front and center in "The Matrix Reloaded," perhaps frustrating those who'd like to see more screen time for Neo and Trinity. Morpheus has a rival in Zion, the by-the-book Commander Lock (Harry Lennix), whose girlfriend, Captain Niobe (Jada Pinkett Smith), keeps making eyes at Morpheus, who's in fact her ex. A new member of Morpheus' crew, Link (Harold Perrineau), seizes the Homeric opportunity to replace his lover's two brothers, slain in the first film, even though she'd rather he stayed home. Seen against the backdrop of Zion society, Morpheus himself becomes a far more complicated character; charismatic and unflappable as ever, he's also something of a hothead outsider whose evangelical obsession with Neo may be interfering with his better judgment. There isn't a ton of room for nuanced acting in these overcrowded films, but Fishburne remains the standout, supplying depth and melancholy alongside the almost architectural beauty of Reeves and Moss.

What we don't know -- and aren't likely to figure out, at least not until the final chapter of this trilogy, "The Matrix Revolutions," reaches theaters in November -- is whether the crunchy, liberated, polysexual and anti-racist society of Zion is really as free from the all-consuming software code of the Matrix as it thinks it is. (Reportedly, the filmmakers wanted the unusually brief interlude between sequels to be even shorter, no more than a couple of months, but the honchos at Warner Bros. refused.) As I say, between the show-stopping fight scenes in "The Matrix Reloaded" the Wachowskis are almost relentlessly devoted to muddying the waters. For one thing, there's a widening schism among the rebel population, between the small group led by Morpheus who believe that Neo (the liberated human formerly known in the Matrix as computer programmer Thomas Anderson) is the One -- as in, you know, The One -- and a skeptical majority who aren't convinced. (Let the historians figure out how closely this stuff mirrors the split between Jews and early Christians living under the Roman Empire.)

What's that you say? Of course Neo is the One, right? (I mean, easiest anagram ever, dude!) It sure looked like that way at the end of "The Matrix," when he had developed powers heretofore only known to Superman, the deities of various religions and super-enlightened monks in Hong Kong movies. Remember, however, that he had developed such powers within the Matrix, which complicates matters more than a little, since nothing in the Matrix is what we would call real and the very existence of the Matrix, as Morpheus is all too eager to point out, destabilizes the nature of reality so much that it never quite seems stable again.

(Is now a good time to bring up the fact that a line spoken by Morpheus to Neo in the first film -- "Welcome to the desert of the real," which itself draws on a trademark Baudrillard phrase -- was borrowed by Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Zizek for the title of a brilliant, troubling essay about Sept. 11 and its aftermath? And the fact that, in the scene where Morpheus speaks the line, as he shows Neo the all-too-real ruins of 21st century civilization, destroyed in the losing war against the machines, the burned-out hulks of the twin towers are clearly visible in the background? There is no spoon.)

So yeah, Neo appears to be the One. When Neo, Morpheus and Trinity, along with a new supporting crew, plunge back into the cool, blue-lit realm of the Matrix -- carefully distinguished, by cinematographer Bill Pope, from the ruddy earth tones of Zion -- and pay a return visit to the Oracle, she more or less tells them so. (Mind you, she more or less told Neo he wasn't the One in "The Matrix," but let's keep moving.) The Wachowskis, true to their nature, want to grapple with bigger questions than that one. What does being the One really mean -- and is it such a good thing? Where does the powerful myth of messianic salvation come from? Isn't it, in its own way, just another system of control?

Along the way to these quandaries, of course, Neo must confront a baroque array of Matrix-villains. Something very strange has happened to Agent Smith, who thanks Neo for "setting him free" from the Matrix but clearly has his own, highly unfriendly agenda and can replicate himself like, well, a virus. In perhaps the movie's wittiest scene, the Oracle sends Neo and company to visit a decadent rogue entity called the Merovingian (Lambert Wilson), who amuses himself with orgasmic-chocolate software programs and is guarded by dreadlocked demonic albino twins (Neil and Adrian Rayment) whose nifty superpowers almost match Neo's. (The Merovingian's disgruntled wife is played by the pulchritudinous Monica Bellucci, who gets a small but seductively significant moment.)

It seems the Merovingian -- and I promise I'll stop short of giving away anything major here -- has under his control a guy called the Keymaker (Randall Duk Kim), who can offer Neo and friends access to secret back passages that lead outside the Matrix but aren't in the so-called real world either. (I was reminded, perhaps inevitably, of the institutional-looking corridors beneath and behind Disneyland.) Then there are Neo's troubling dreams, and the promise he extracts from Trinity that she won't come into the Matrix after him if he's in trouble. (Will she keep it? Duh!)

Keanu Reeves is regularly abused for his granite-faced acting, and I understand what people mean, but I actually find his presentational style in the Matrix movies highly effective. Neo is a guy who has gone in some relatively brief timespan from being a disaffected computer geek, awkward around other people, to a near-omnipotent superhero with a wicked-hot girlfriend who wears vinyl catsuits. His amazement at the pilgrims camped outside his door in Zion, or at the alarming, almost exponential expansion of his powers (I'm not telling!), or even at watching the "little death" of Trinity's orgasm as they make love feels completely legitimate.

That moment of orgasm, coming at the end of the extraordinary dance-sex sequence described earlier, essentially made "The Matrix Reloaded" for me. In fact, I trusted the Wachowskis after that, in a way I've never quite trusted them before. No, I'm not sure where they're going or quite how they're going to get there, but I know I want to take the ride. I've lost all sympathy for the flocks of chicken-robots who will gather around this franchise trying to peck holes in it, complaining about this or that problematic stunt scene or red-herring character. They are the agents of the Matrix; ignore them. Finally I understand that the Matrix movies are striving for a massively contradictory epic about love and hope, a grand and maybe impossible vision of living in a world of technology and escaping it at the same time, of being truly alive in a dead or dying society. They kick major ass, and they show us a future worth fighting for.

Shares