Children are natural philosophers, perhaps because they have so much to resolve if they’re to have any hope of getting along in the world. Such as: Why do things fall when I drop them? Do they always? How can my mother tell when I’m lying? Is she? Will it be morning again tomorrow? How do I know whether I’m awake or dreaming? And a mind that’s building a philosophy to live by doesn’t stop at the practical questions. Where does the moon go in the day? Did the world really exist before I was born? When will I get to be older than my big sister? How do I know I’m really me?

When I was 7, I used to lie awake at night wondering about infinity. I would imagine myself swimming up from my bed into the darkness of space, on and on, out and out. It had to stop somewhere, I thought, so I imagined a brick wall marking the end. But what was beyond the brick wall? Sometimes I broke through into more darkness, miles of it, hours of it, until the emptiness made me panic and I added another wall — only to break through it into more space. Sometimes, to stave off the darkness, I would imagine the wall extending in its red-brown solidity, filling the space beyond it with bricks and mortar, until that, too, became oppressive. Eventually, unnerved, I’d crawl into bed with my parents.

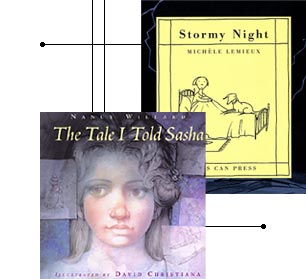

The narrator of Michéle Lemieux’s fascinating “Stormy Night” has an uncannily similar experience. “I can’t sleep,” she tells us. “Too many questions are buzzing through my head. Where does infinity end? If someone made a hole in the sky, would we see infinity? And if we made a hole in that hole, what would we see?”

Like a cosmonaut moving from hole to hole, the book takes its readers through one simple but profound query after another, each illustrated with a pen-and-ink drawing — over 200 pages of them. It’s an unusual yet satisfying format, inviting young philosophers to dwell, or, if they prefer, to dip in and duck out. There are several months’ worth of bedtime koans here.

In her drawings — gentle cartoons with a surrealist flavor — Lemieux extends the text, rather than giving literal illustrations. For example, the comment “Sometimes I feel as if my eyes can see inside me” faces a sketch of a boy sketching; the top of his head is transparent, and inside we see a man holding aloft a lantern. At his feet, a staircase leads down, possibly into the boy’s nose. “I’m scared of being separated from everyone I love” shows a cake decorated with a village — houses, poplars, a church. A slice is being carried away on a cake server, topped with a tiny figure that stretches its arms toward the village. And Lemieux illustrates the question “What about me — do I have an imagination?” with a picture of her heroine looking through a spyglass pressed to a mirror. Can she see her own eye in the darkness?

The narrator of “Stormy Night” worries a lot about the future and her place in it. “Will my name be in the encyclopedia?” she wonders. “If we could switch bodies, would someone choose mine?” “Will I always make the right decisions? And how will I know if they’re right?” But while these questions may seem personal, the narrator is a kid with a speculative mind; they always open out into broader inquiries. Her journey is a little scary perhaps, but she has a dog, Fido, to keep her company through her philosophical night. At the book’s end, after peeking through that hole in the sky at possible afterworlds, she falls asleep at last. Readers who have followed her twisting path to sleep can amuse themselves imagining what she finds there.

Sleep is likely the setting for another philosophers’ treat, “The Tale I Told Sasha.” At any rate, the author, Nancy Willard, seems to hint as much by taking her epigraph from “Through the Looking Glass,” that great philosophical dream. Like Lewis Carroll’s Alice books, this tale is about a voyage through a quasi-nonsensical landscape riddled with dreamlike logic. The narrator, a little girl about the same age as Lemieux’s heroine, chases a yellow ball through the shadow cast by a mantel clock (more shades of Alice, who climbs up on her mantelpiece to go through the looking glass), then follows it through a fantastical world. She encounters a boy with a red balloon, then a golden fish. She passes through the place where lost objects congregate: a dropped needle, puzzle pieces, that card that’s been missing from the deck for years. At last she finds a farmer, the King of Keys, who helps her with her quest.

Willard is one of the most musical poets around, and only my respect for copyright law keeps me from quoting this lovely lyric in its entirety. It begins with deliberately modest restraint:

Mother gave me a yellow ball

because the day was wet and dull.

Our dining room was dark and plain.

Our living room was plain and small.

When the narrator passes through the clock’s shadow, however, her plain words soon take on a chiming richness. She meets a guide, who tells her:

“All winged travelers must walk.

All those with wheels get to ride.”

He did not warn me of the web

that shimmered on the other side.

Though Willard’s “twilight sherbet, pansy creams, /and starlight-covered jellybeans” may be too sweet for some tastes, she undercuts them with sleeping tigers, roses astonished by the frost, and creeping shadows.

David Christiana’s illustrations — bright, muddy watercolors — amplify the text they illustrate; too bad they didn’t go further. The King of Keys plays a guitar with birds and houses for tuning pegs — a nice addition. And when he throws the yellow ball home for the narrator, he first opens a wall between worlds by undoing an enormous zipper. It’s an absurd, appropriate image. Christiana also makes some wise choices about what not to illustrate (“a hundred pencils, swift as rain” are much better left to the imagination). But I wish he hadn’t given the characters such cute faces. An illustrator with a darker vision — such as Barry Moser, who collaborated with Willard on several earlier books — might have done a better job of keeping the occasional sweetness of the text from cloying.

What does it all mean? Like a dream, it’s impossible to know, but its atmosphere will linger, full of portent and promise, all through the day. How lucky readers are that Willard’s publishers trust her enough to let her get away with such beautiful nonsense.