Sally bounds up the stairs two at a time. She fumbles with the key, then bursts into the lab. With fingers still frozen from the morning air, she takes a tray of hockey-puck-size clear plastic cups out of an incubator. The cups contain fish embryos and water. She drops some of the fluid onto a slide and looks through the microscope. There they are, little spheres with dark paisley inlays.

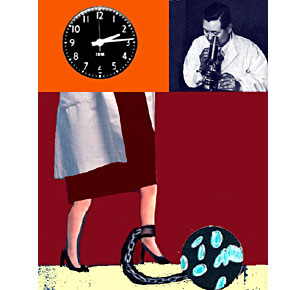

These particular fish are growing without hearts because Sally knocked out a gene fish need to grow hearts. She can now study this missing gene by watching what doesn’t happen in its absence. She had to get the fish out of the incubator at exactly this stage of development — just as the organs are forming, but before these fishlings die when they discover they have no hearts. Having not left the lab until midnight, Sally overslept the 6 a.m. alarm.

Poor Sally. With wan skin and greasy hair, she looks like a drowned mouse in bed-rumpled clothing. Sally repeatedly scratches her left underarm. Sally (not her real name) is a post-doctorate, one of 40,000 scientists in America caught between graduate school and professorship. They are science’s slaves, indentured to the promise of an academic job and whipped by the fear of not getting that job. So they toil like Sally: 80 hours a week for less than $30,000 a year, running her advising professor’s lab, doing his research and writing papers that redound to his greater glory as much as her own: It used to be that Ph.D. candidates and post-docs would do the work while the professor hogged the credit; these days they share the credit, though not the work.

Sally likes her advisor. He always acknowledges her efforts, and he is doing his best to get her a faculty position somewhere. But he also relies on her sweat. These fish-embryo trials have to be completed before he gives a presentation at a summer conference. He’s not the one getting up at 6 every morning, and he won’t really be writing the presentation. But Sally must “keep up the good work” until she herself becomes a professor.

According to Eleanor Babco of the Commission on Professionals in Science and Technology, no one tallies how many science faculty positions are vacated every year, but it is clearly not enough to hire each year’s group of science Ph.D.’s, because the pool of in-limbo post-docs keeps growing. Non-science Ph.D.’s don’t have such a formalized system. They can be lucky enough to get a professorship right away, they can jump to another line of work before returning to the academy or they can drive a taxi.

Science Ph.D.’s are not allowed to leave if they ever want a professorship. They are put into this bottleneck, this holding pattern called the post-doc where they must work as hard as they absolutely can in order to stand out and be chosen. Sally cannot afford to sleep in. She cannot afford to take time off. She cannot afford to give her real name to the press because complaining is looked down upon. All she can do is hope hope hope that some department somewhere will someday hire her on as an assistant professor of genetics at $42,000 a year.

Sally is single, lover-less and 32 years old.

Among a number of “Far Side” cartoons about eccentric scientists, she has posted a news clip over the lab table: “Law firm raises starting salaries to $150,000.” “Those kids are 24,” Sally says. “They did three years of grad school. Are they worth that much more than me?”

Academic science, especially in the biological fields, has grown healthily in the past decade. But the research and the lab work have become more complex, requiring more worker-hours to run a scientist’s lab. The overproduction of Ph.D.’s provides science professors a source of cheap, high-quality labor. Most post-docs find they have no alternative. What could they do? Drop out after eight years of education? Leave the august halls of Newton, Einstein, Pasteur and Gould?

“It’s unthinkable to most,” says Sally as she scribbles some numbers into a lab book. “Unthinkable for two reasons: One, you say to yourself: ‘Here I am, I have been growing fish embryos for eight years. I am very good at it. Who else in the world cares?’ You have dedicated your life to something so narrow, so inconsequential, that you have to see it through to consequence. You wait it out and publish with the hope that your work is someday cited by some researcher who discovers something else that a decade later leads to a new drug to cure cancer.”

Sally scratches her armpit and checks to see if I noticed. The second reason dropping out is so hard, she continues, “is the science-is-an-elite-club mentality. Maybe it’s that scientists were always geeks and so when we succeed, we say non-scientists are a second class of intellect. Whatever the reason, most career-track scientists think that people who go another direction are failures, pure and simple.”

Indeed. In mid-February, I attended a “Career Alternatives for Scientists” workshop at the annual conference of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) in Washington, D.C. A room full of post-docs heard from a panel of former career-trackers who had jumped the rails. One is now a program officer for a philanthropic foundation. Another works at the U.S. Patent Office. One is a science writer. For all of them, life has improved: They are using their scientific training, working sane hours and making more money than most professors. Just as importantly, they joined the real working world — people at cocktail parties understood what they did.

Was this a battle cry of freedom? No. It was an I’m-OK-you’re-OK therapy session designed to exorcise the Goliath guilt they all felt over the very thought of leaving the traditional track: “Scientists stop talking to you — you cease to exist,” one panelist exclaimed, ” “How dare you squander your Ph.D.!’ And normal people say, ‘So why’d you do the Ph.D. in the first place?'”

“It’s OK, you guys!” another panelist reassured them. “You’ll always be scientists! You’ve done the training. And I promise, you’ll get over the feeling of failure — paychecks help!”

As I sat among these kvetching post-docs, I thought of natural selection, Darwin’s theory of evolution. To simplify (with apologies to Darwin): Nature produces more animals than the environment can support. These animals differ from one another over a wide range of attributes (in nature, we are talking about giraffes with long necks and giraffes with short necks). Nature then takes this overabundance and variability and wipes out those animals with the wrong attributes — it selects for the animals that fit the environment.

I wondered if academic scientists might view these tail-between-the-legs program officers and science writers as having died out — gone extinct from science because they weren’t the best scientists. The academy has room, the reasoning goes, for only the best scientists; the over-production of Ph.D.’s combined with the thinning out process of the post-doc bottleneck is very healthy — it’s Darwinian. It leads to the finest scientists.

I asked one of the panelists, a National Institutes of Health (NIH) official, if he had encountered this argument. “Definitely, there are many who think that,” he said, pointing vaguely to the rest of the AAAS conference. “But they’re wrong. There is a selection, but it’s not a selection for the best. It’s only weeding out the people who don’t want to destroy their lives for the sake of publishing papers on potassium ions in protein folding.”

Aha! A subtle and proper Darwinian distinction: Animals are not selected for the best attributes, they are selected for the fittest attributes, as defined by the environment. In a world with no trees the short-necked giraffes are better adapted. The slavish environment of post-doc-dom doesn’t reward ability as much as it does tenacity.

The program officer, Victoria, had a risumi packed with the right papers in the right publications. Her choice to go into a non-traditional career did not reflect poor promise in science. Rather, she wanted to work normal hours. She wanted a wage that reflected her abilities. There was more to life than studying oyster-hosted bacteria; as she put it, “Since I was planning to die sometime in the next 50 years, I thought I’d vary things a bit.

And if the overproduction of Ph.D.’s leads to intense competition and a hellish lifestyle, but does not end up selecting the best scientists — only the most fiercely competitive — then why run the system that way? The NIH official, who asked not to be named but whose position gives him a systemwide perspective, has an answer:

“Science has become addicted to cheap labor,” he explains. “The established scientists love having people who are going to bust their ass for them 14 hours a day, seven days a week. Post-docs are the life-blood of science: They are up on all the new technologies and techniques, the know the literature, they are good at writing papers and teaching grad students.” He strokes his beard and looks at the floor for a moment, and then adds, “Who wouldn’t want that? It’s a great system for the senior scientists to have all these slaves working for them. Of course, it can’t last. Abusing the middle folks, the post-docs, won’t help in the long run — because you’ll lose them.”

I tell him about my friend Bill, who is fleeing a neuroscience post-doc at Stanford for a Silicon Valley start-up at the end of the academic year. The job description involves computers and neural networks, so he’ll use his neuro background. He’s something of a new man since he made the choice. He talks about the next step with an excitement I have never seen in him. He says the people he’ll be working with are brilliant and the ideas necessary to their company are as complex and challenging as any of his academic work. He will triple his pay. The NIH official is not surprised. “Folks who should be moving up are finding other careers. And so they should. We all did.”

In today’s world, the academy has only indoctrination on its side — the notion that all Ph.D.’s seem to buy into that to be a scientist is to be a member of an elect priesthood. But listen now to that grand sucking sound; I.T. money, the biotech revolution. There’s science to be done and money to be made, regardless of what those who still wear medieval hoods say about selling out. The NIH official fears an over-correction — that too many will drop out of academic science. But if it happens, one could venture, it’s just nature’s way of finding the right balance.