Sir Thomas Crapper did not really invent the flush toilet. The word "gringo" was not inspired by the American troops who sang "Green grow the grasses-o," during the Mexican-American War -- the word was in use 100 years previously. Still, those popular misconceptions and countless others survive through constant repetition, and someday they will be joined by new linguistic fables even now being born.

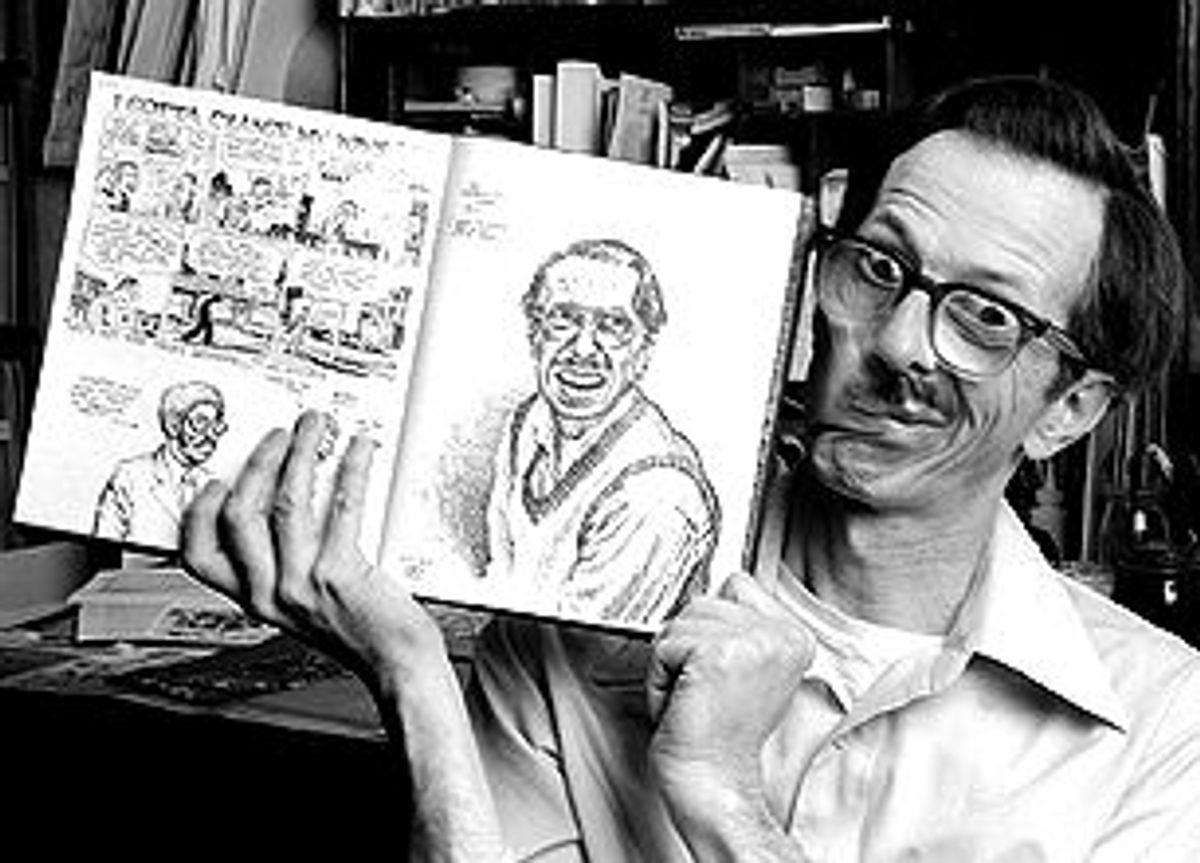

Here's a likely candidate -- years from now it will be widely circulated that the word "crummy" derives from the work of cartoonist Robert Crumb, a world-class malcontent of the late 20th century. Crumb surveyed the urban landscape of his era and pronounced his verdict: Everything sucks big time, including humanity and, most especially, Robert Crumb. "At least I hate myself as much as I hate anybody else," Crumb once said. Coming from the author of "Self-Loathing Comics," you can take that to the bank.

Crumb certainly did. His status as the bull-goose legend of underground cartooning meant that in the early '90s he was able to trade six of his sketchbooks for a house in the South of France. But Crumb's career has never been about maximizing financial possibilities -- that would mean signing on with mainstream pop culture, which Crumb, of course, despises. In fact, Crumb's repeated rejection of commercial opportunities (he once turned down an offer to do a Rolling Stones album cover because he hated the band) marks him as one of the last remaining exemplars of the egalitarian '60s hippie ethos he came to represent for so many people.

There's only one problem with this -- Crumb despised the '60s hippie ethos he came to represent for so many people. And the '70s sucked even worse and he's not that enthused about drawing and he really hates Bruce Springsteen. "The only burning passion I'm sure I have," he once said, "is the passion for sex."

Robert Crumb was born in Philadelphia on Aug. 30, 1943, to a Marine father and a devout Catholic mother. His first cartooning efforts were inspired not by love of the art form but by sibling dynamics -- as the third of five children young Robert inevitably fell under the sway of his oldest brother. "Charles forced me to draw comics," Crumb recalled in "The R. Crumb Coffee Table Art Book" (Back Bay Books). "If I didn't draw comics I was a worthless human being. It was tedious labor, so I worked fast to get it over with."

Crumb and his brothers soon became experts on the comic form, treasuring late '40s work like Little Lulu and, later, Walt Kelly's Pogo. The 1995 documentary "Crumb," directed by the cartoonist's friend Terry Zwigoff, unforgettably details the Crumbs' suburban gothic world -- a father described as a "sadistic bully" who broke Robert's collarbone at age 5, a mother hooked on amphetamines and, down in the trenches, a fierce three-way fraternal rivalry dominated by the increasingly reclusive and unbalanced Charles.

Crumb's burgeoning misanthropy was stoked, as is so often the case, by adolescence. "I realized I was a geek and I wasn't going to make it with the girls," Crumb wrote. "I felt so painfully isolated that I vowed I would get revenge on the world by becoming a famous cartoonist."

In the late '50s young Robert discovered Mad magazine and later Humbug, which introduced him to the work of Harvey Kurtzman. "I lived, breathed and ate the pages of his magazines," Crumb recounted in a 1989 cartoon called "Ode to Harvey Kurtzman." "I was truly in love."

In 1962 Crumb got his first real job as an illustrator at American Greetings in Cleveland. The tedious grunt work had him on the brink of quitting until he was elevated to the role of illustrator for the slightly edgier Hi-Brow line. (Crumb's boss was future Ziggy creator Tom Wilson, who encouraged Crumb to make his drawings "less grotesque." Crumb claims it took years to expunge the resulting "cuteness" from his work.) After sending an early Fritz the Cat cartoon to Kurtzman at Help! magazine, Crumb received the following note from his boyhood idol: "We really liked the cat cartoon, but we're not sure how we can print it and stay out of jail."

But print it they did. Soon Crumb was working as Kurtzman's assistant at the short-lived Help! (where the staff included future Monty Python animator and filmmaker Terry Gilliam).

"My dad always said I'd marry the first one who came along," Crumb remarks ruefully in one autobiographical strip. That turned out to be Dana Morgan. "Big mistake," Crumb later wrote -- the new husband was just 21 years old and chronically broke. Nearly destitute, the couple traveled in Europe while Crumb continued to do work for Kurtzman and American Greetings. Dana stole food.

The turning point in Crumb's career came in 1965 -- specifically, it came in a little glass vial. "LSD was legal the first time I took it," Crumb wrote. "The first trip was a completely mystical experience ... It was the Road to Damascus for me. It completely knocked me off my horse and altered the way I drew. I stopped drawing from life."

With the exception of Fritz the Cat, all of Crumb's best-known creations date from his post-acid phase, including his most inspired character, Mr. Natural. Crumb's bearded little guru is no con man -- he's too unapologetic for that. A straight-talking sybarite (booted out of heaven for telling God it's "a little corny" in "Mr. Natural Meets God"), Mr. Natural is chronically plagued by tight-ass neurotics like Flakey Foont and Schuman the Human, and may be the only Crumb creation who can genuinely be described as likable.

Zap Comics, consisting entirely of Crumb art, debuted in 1967, with the artist and his wife selling the first issue on San Francisco street corners. Underground comics are now remembered as an indispensable part of the era, but it was Zap that blazed the trail. "The people who ran the hippie shops looked at Zap and said, 'Comic book? What do we want with a comic book?'" Crumb recalled.

They figured it out fairly quickly. Crumb's rambling, hallucinogenic, sexually explicit cartoons became the visual expression of the Haight-Ashbury scene. Particularly potent was his "Keep on Truckin'" image from Zap #1. Inspired by the language of the '20s- and '30s-era blues recordings that Crumb collects obsessively, the famous cartoon depicts a goofy parade of big-footed pedestrians doing an exaggerated strut down the city streets. It was soon regurgitated onto posters, T-shirts and head-shop memorabilia, mostly without Crumb's permission or participation. (Eventually the cartoon caused legal and financial headaches for the artist -- in 1976 a judge ruled that the image did not belong to him, and subsequently the IRS pursued Crumb for unpaid taxes stemming from royalty payments.)

As an unpopular kid, Crumb had longed for the sweet revenge of fame. As a gawky adult in San Francisco, he longed for a little of that free love supposedly floating around. And suddenly, it happened -- the candy store was open. Keep on Truckin', along with Fritz the Cat and his cover art for Big Brother and the Holding Company's "Cheap Thrills" album, helped make Crumb famous, an icon of the hippie scene and a babe magnet.

He reacted with contempt. Crumb felt scorn for the hippies, the women, the commercial exploitation, even the work itself. Keep on Truckin' in particular inspired his disdain, a theme that he revisited more than once. In a 1990 cartoon about the creation of the iconic image, Crumb described pop music as "the rhythms of cultural death. In my own spaced-out, inarticulate way, I tried to draw the images I saw in my mind when I heard modern pop music on LSD ... clownish fools boppin' and jivin' in the garbage heap they were making out of the Earth. ... I was fooled by my own drawings. Other people thought they were happy images of relaxed cartoon characters just havin' a good ol' time ... so I did too! I forgot what they really were. Photographs of the dance of death!"

Well, fair enough -- but as Crumb points out elsewhere in the same cartoon, "I guess I don't like to see people having a good time." Most of Crumb's work is suffused with the sullen attitude of the high school loser who has never escaped the cloud of early rejection. "The instant I realized I was an outcast I became a critic," Crumb has said, "and I've been disgusted with American culture from the time I was a kid. I started out by rejecting all the things that the people who rejected me liked, then over the years I developed a deeper analysis of those things."

In an essay from "The R. Crumb Coffee Table Art Book," the artist describes his passion for old 78s that began when he heard "Happy Days and Lonely Nights," a 1928 record by Charlie Fry's Million Dollar Pier Orchestra. Enthusiastically, Crumb avows his love for this old music and other artifacts of the era. The essay is titled: "To Be Interested in Old Music Is To Be a Social Outcast!"

There's probably some pleasure to be had from it, too, but I suppose that can't be helped.

By late 1969 Crumb had hooked up with S. Clay Wilson, Victor Moscoso, Rick Griffin, Gilbert Shelton, Spain Rodriguez and Robert Williams to create the seven-member Zap Collective, which published copies of the magazine sporadically for the next two decades. Crumb also turned out voluminous work in publications with titles like "Weirdo," "Black and White," "Big Ass Comics" and "People's Comics," in which he killed off Fritz the Cat in 1972. (Not surprisingly, Crumb loathed "Fritz the Cat," the Ralph Bakshi

animated film that starred his randy feline.)

Crumb is neither a gag writer nor a yarn-spinner. Aside from occasional flights of fancy and the visions dredged from his subconscious with an acid shovel, most of his work is autobiographical. Crumb cartoons are typically marked by a painful, neurotic honesty -- also, women with shelflike asses and legs like telephone poles. "My personal obsession for big women interferes with some people's enjoyment of my work," Crumb wrote in "The Coffee Table Art Book." "I knew it was weird and disturbing and even offensive to a lot of people, particularly women. But I couldn't keep it out of the comics. I would always try to give it some sort of metaphorical sense because I derived such masturbatory pleasure out of drawing these women in bizarre situations with these little guys doing stuff to them. Similarly, using racist stereotypes -- it's just boiling over out of my brain, and I just have to draw it ... All this stuff is deeply embedded in our culture and our collective subconscious, and you have to deal with it."

To reveal your own dirty laundry is one thing -- to have it exposed onscreen is something else, as Crumb and his second wife, Aline Kominsky, discovered in 1995 with the release of Zwigoff's documentary. The director was an old friend and fellow member of the Cheap Suit Serenaders, the group Crumb formed in the '70s to play his beloved old music. Winner of the grand jury prize at the '95 Sundance Film Festival, "Crumb" was a revelation -- a sometimes creepy and always fascinating journey that did far more than simply enumerate the artist's renowned peccadilloes. Robert may be a seething cesspool of misanthropy and sexual neuroses, but after a couple of scenes with older brother Charles and younger brother Maxon, Mr. and Mrs. Crumb's second boy begins to look positively mundane.

Maxon is the film's purest comic relief -- a late-blooming artist of genuine talent, his other hobbies include attempting to molest Chinese women on the street, pulling women's pants down in department stores, sitting on nails for hours on end and eating long cords of rope that take three days to shit out. "It gratifies the intestines," Maxon explains.

Charles, made passive and easygoing by tranquilizers and antidepressants, evokes more complex reactions. A benign, housebound Buddha ("Can you give me one good reason for leaving the house?" he asks rhetorically), Charles' mild manner and toothless grin belie the darkness he describes. Late in the film he calmly reveals that, in his teens, he struggled with the powerful urge to stab Robert to death in his sleep. Sitting cross-legged on his bed, Charles reviews his life with the bemused detachment of a fired coach recalling a championship game lost years ago. "Believe me," he chuckles about his morbid solitude, "it's nothing to envy."

Charles developed an early fixation on the 1950 Disney movie "Treasure Island," starring Robert Newton as Long John Silver and Bobby Driscoll as young Jack Hawkins, filling reams of paper with variations on the story. In one scene, Robert reveals that the source of Charles' Treasure Island obsession -- a sexual fascination with Driscoll -- emerged only years later. Young Robert, dutifully slaving away at their pirate comic serials, had no clue as to the true nature of Charles' inspiration. In that way at least, their intense fraternal relationship was fairly typical -- big brother's actual motivations are rarely perceived by slavishly imitative little bro. It's a religion, and as with any religion, you don't ask questions.

The film's most disquieting moments record the contents of Charles' old sketchbook. With each page the "Treasure Island" characters become smaller and smaller, pushed to the bottom of the frame by an increasing torrent of words. Then there is nothing but writing and finally, terrifyingly, page after page of cursive lines -- like the CAT scan of a brain's descent into madness. It's eerily reminiscent of the "All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy" scene in Kubrick's "The Shining," but with the considerable added impact of reality.

Perhaps saddest of all is Robert's memory of how the unpopular and prematurely embittered Charles spread the virus to his siblings. Any display of enthusiasm on Robert's part would be squelched by Charles' trademark sneer: "How perfectly goddamn delightful it all is, to be sure." Charles, the closing credits reveal, committed suicide a year after being interviewed for the film. Robert's life and career begin to look heroic by comparison. (Art and writings from Charles and Maxon can be found in "Crumb Family Comics," published in 1997 by Last Gasp of San Francisco. The collection also features work by son, Jesse -- born to Robert and Dana in 1968 -- daughter, Sophie, and Aline Kominsky-Crumb. Although Kominsky's best-known work has, not surprisingly, involved collaboration with her legendary husband, the native of Long Beach, N.Y., was already cartooning when they met in the early '70s. Kominsky's characters include Blabette Yakowitz, based on her mother. She and Crumb married in 1978. Sophie was born in 1981.

The documentary also neatly summarized the opposing critical camps that have formed around the artist's work. Leading the cheering section is Time magazine art critic Robert Hughes, who calls Crumb "the Breughel of the last half of the 20th century," and also compares him to Goya. For the prosecution, Deirdre English, former editor of Mother Jones, examines Crumb's 1969 epic "Joe Blow" (the target of obscenity busts at comic stores), a gleeful tale of incest in a picture-perfect Eisenhower-era family. She sees something other than satire. "You sense that Crumb is getting off on it himself," English says, "and I think this theme is omnipresent in his work. It's part of an arrested juvenile vision."

Crumb himself pleads ignorance. "I don't work in terms of conscious messages," he tells Zwigoff. "I can't do that. It has to be something I'm revealing to myself as I'm doing it."

Crumb had mixed feelings about "Crumb," which, naturally, he expressed in cartoon form. "Head for the Hills" was published in the New Yorker in 1995 and contains Robert and Aline's ruminations on Zwigoff's project: "He was kind of creatively at a loss and we felt responsible for his well-being," Crumb says in the strip. "So we let him film the intimate details of our life." "He kinda used us to push his own ideas," says Aline.

Zwigoff doesn't disagree. "People don't seem to understand that 'Crumb' is a very subjective film," he later wrote in the collection "Family Album." "What the film reveals about me is as much a part of the equation as what the film reveals about Robert."

Whatever Crumb's feelings about the film, it frequently paints a more sympathetic portrait of the artist than the one presented by his own published work. Reading collections of Crumb cartoons can be an enervating experience. It's true that for someone like Crumb, who possesses the required taste and discernment to appreciate folk traditions, today's trash culture can seem like the sixth pot of tea from the same withered bag. Regardless, Crumb frequently comes off as a determinedly miserable sod. He wanted fame, got it and despised it. He wanted women, got them and hates them. Crumb's anti-consumerist ideals are definitely '60s vintage, but he can't seem to decide whether he misses the decade or loathes its memory.

But Crumb's saving grace is Crumb himself. There is virtually no criticism you can make of him that he hasn't already made -- his most merciless gaze is usually directed into the mirror. The same 1990 cartoon that contains his attack on those who love his most famous image -- "So Keep on Truckin', Shmucks!" Crumb jeers in the final panel -- also features a postscript by Mr. Natural: "Don't forget, Bob, that it was the compassion, the loving forgiveness, that they found so appealing in your cartoons, that made you so popular, that got you laid, that earned you a living. Keep it in mind!"

Well said, Bob -- er, Mr. Natural.

Moreover, Crumb's critics depend on Crumb for their ammunition. Attacking the man as a misogynist? Sure -- you know it because he told you so in cartoons like My Trouble with Women, Parts I and II. The cartoonist's commitment to brutal honesty is the most consistently admirable aspect of his work. Casual readers, too, need to remember that their information about Crumb comes largely from the source. "We only tell 'em what we want them to know," says Crumb in "Head for the Hills." "An' they assume it's all true," adds Aline.

Zwigoff's documentary also highlights a man who, whatever his failings, is certainly no hypocrite. Big money deals, the Rolling Stones, the chance to host "Saturday Night Live" (in 1976 when it would have meant something) -- Crumb spurned it all. Fellow cartoonist Bill Griffiths (Zippy the Pinhead) says admiringly, "This is not something you see every day in America, where selling out is everybody's ambition."

"Crumb, like all great satirists, is something of an outcast in his own country," Hughes remarks in the film. Father of Mr. Natural, murderer of Fritz the Cat -- Crumb's repudiation of modern America will remain trenchant, particularly for the underground culture that has always been his natural home.

But if you choose to immerse yourself in the collected works of Robert Crumb you might subsequently find yourself with a certain craving -- the urge to draw the drapes, throw "Saturday Night Fever" on the stereo and do the Dance of Cultural Death till you puke. And then thank your lucky stars that you're so easily amused.

Shares