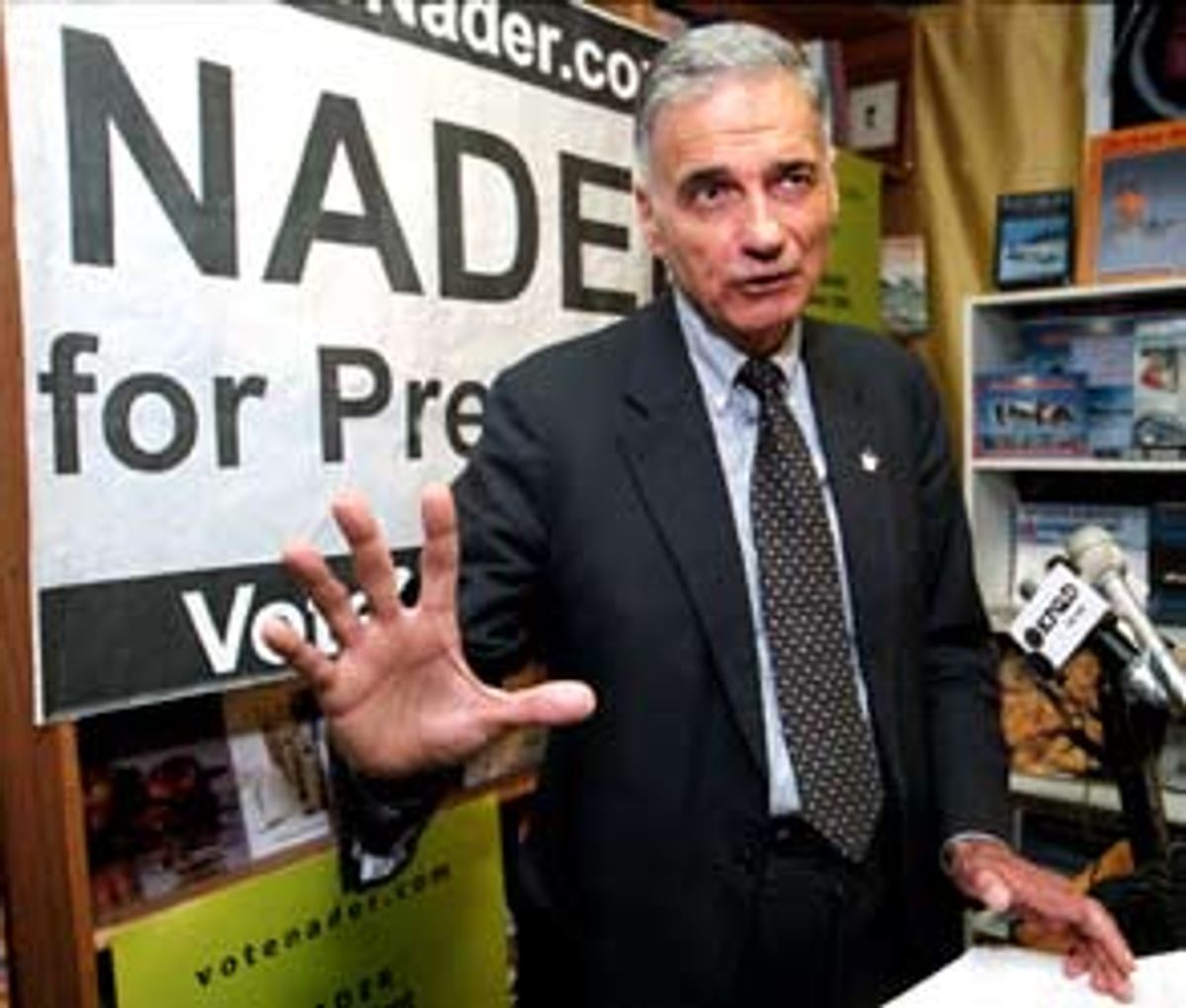

Should we think any less of consumer advocate Ralph Nader when we find out he's a multimillionaire?

Over the weekend several publications, including the Washington Post, published interviews with Nader, the soon-to-be-nominated Green presidential candidate, in which, for the first time, he details his own not-inconsiderable personal wealth. Nader told the Post he believes he's made between $13 million and $14 million over the course of his career; and according to his just-released financial disclosure statement he is worth at least $3.8 million. Even more striking, much of that wealth is invested in a small group of high-flying tech stocks such as Cisco Systems, Comcorp, Iomega and Ziff-Davis.

Because he has heretofore refused to discuss his personal wealth, Nader's conservative critics have long claimed that he has used his various books, speaking engagements and other activities to amass a vast personal fortune. And in his interview with the Post, Nader was clearly eager to preempt any criticism that there is anything inconsistent or hypocritical about his being worth some 4 million dollars. "The question should almost be, 'Why is it so little?' If it was in any way comparable to what these corporate executives are getting, we could've done a lot more," he said.

So is Nader a hypocrite for amassing a personal fortune while advocating consumer rights and railing against corporate power?

In a word, no. To think otherwise would be to buy into the common but thoroughly fallacious argument that pursuing public service and advocacy is somehow incompatible with making a good living. Under this reasoning, someone with no social conscience can make millions upon millions of dollars and still be in the clear, but someone with a social conscience is a hypocrite unless he or she lives like a monk. That's a ridiculous standard. Nader has made countless enemies over the years and the strong and uncompromising stand he has taken on many issues has made many of those enemies eager to catch him out in some instance of hypocrisy.

But even with the fortune Nader has managed to accumulate, he also appears to have donated enough of his personal wealth to the various public advocacy organizations he's founded to get around any charge of hoarding. Nader told the Post he gives away more than 80 percent of his after-tax income and noted, as an example, the fact that he used $500,000 of his own money to fund the Congress Project in 1972.

But if Nader is in the clear for the amount of personal wealth he has accumulated, his choice of stock-holdings is a good deal more questionable. In defending his choice of stocks to own Nader told the Post, "No. 1, they're not monopolists and No. 2, they don't produce land mines, napalm, weapons."

But that's a problem. Because, by many definitions, the company in which Nader owns most of his stock, Cisco Systems Inc., is a monopoly.

The computer industry has three companies which have monopoly or near-monopoly control over their various industry sectors: Microsoft, which controls the PC operating system and much of the applications market; Intel, which controls the PC microprocessor market; and Cisco, which controls a dominant share of the "router" market, basically the plumbing that makes up the Internet and various other computing networks. Cisco controls a bit more than half of the overall data-networking market but has, for example, 89 percent of the market for high-end routers.

Cisco has also been investigated by several government agencies for possible anti-competitive or monopolistic practices. In fairness, none of these investigations have led to charges against the company. But Cisco does pursue many policies aimed at locking in its dominance of the router market and freezing out other competitors. Its market power is so great that three of its strongest competitors have simply dropped out of the running in the last year and Cisco has dealt with many of its smaller competitors by simply buying them and folding them into the Cisco empire. (In one particularly striking move, Cisco entered into an agreement with IBM in which the latter agreed to drop out of the computer-networking business in exchange for payments from Cisco.)

In fact, one of the reasons Cisco has been able to evade serious antitrust scrutiny is that the company goes to such lengths to train employees to avoid Microsoft's mistakes. As the Wall Street Journal reported earlier this month, Cisco's training for its new employees warns employees to avoid inflammatory language in written communications and reminds them that "e-mail, notebooks and hard disks can be looked at by lawyers."

None of this means Cisco is a bad company, but it is an odd choice for Nader. And there's more. As with many other high-tech giants, Cisco's Washington lobbying has been concentrated on objectives like making it harder for disgruntled shareholders to sue their companies -- something Nader and his various groups have vociferously opposed. It has also focused on passing legislation to issue more H1-B visas to foreign workers, while Nader has taken a strong stand against the visas.

So what does the Nader campaign have to say about all this? When I raised the charges of Cisco's monopolistic practices with Nader spokesman Teresa Amato, she asked whether any of the government inquiries into Cisco's behavior had resulted in sanctions or prosecutions. They hadn't, but then that's setting the bar rather low, isn't it? And what about Cisco's lobbying for legislation that Nader has strenuously opposed? "We don't know anything about that," she told me. "Send us whatever information you have. I am sure if we found out anything about that, Ralph would take appropriate action."

Shares