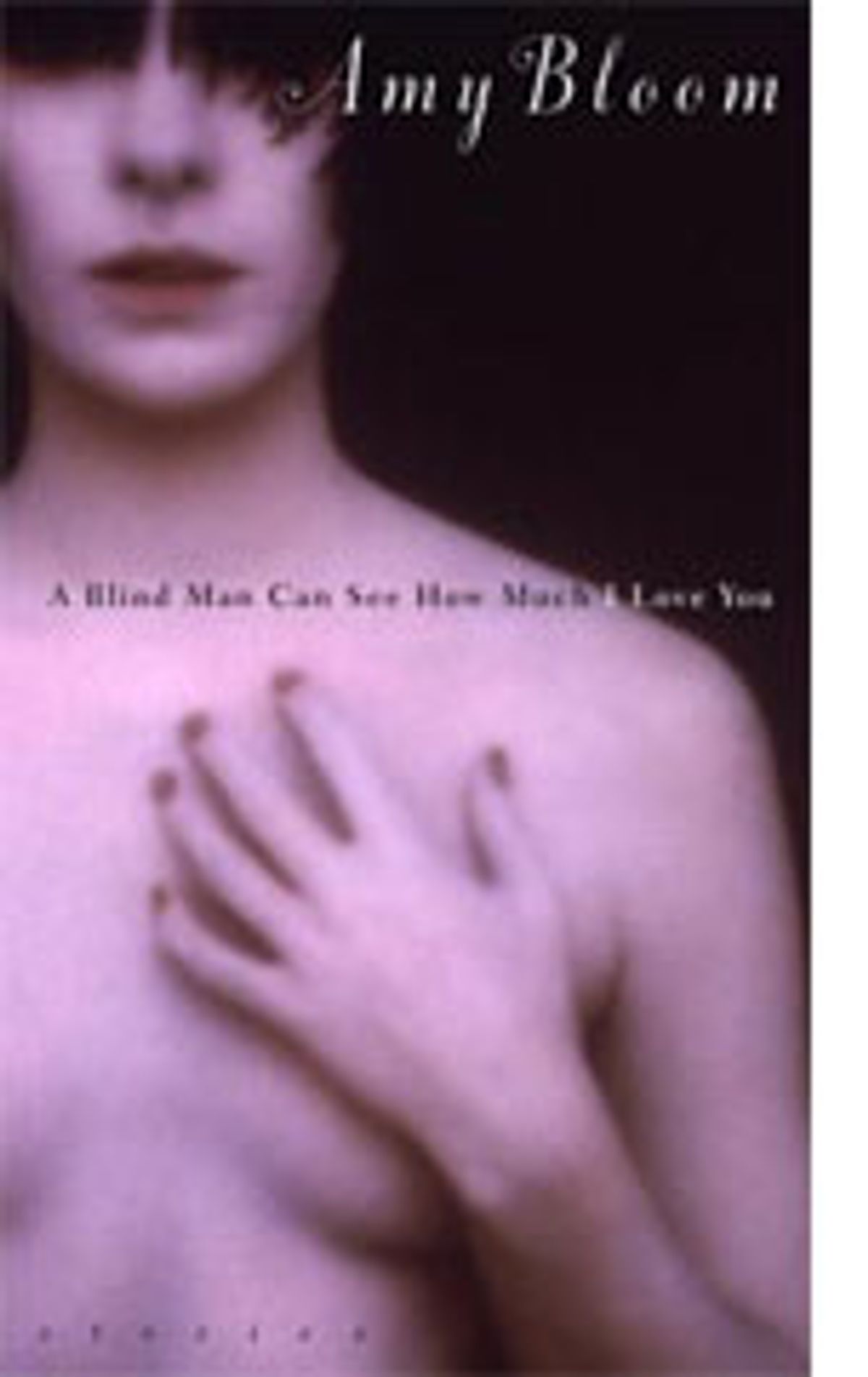

At first, reading Amy Bloom's second collection, her third book of fiction, you might feel lost among the stereotypes, as Jane does in the title story: "Once you know there are transsexuals, you see them everywhere. ... When you walk out of the waiting room of the North American Gender Identity Clinic, everyone looks peculiar. You flip through magazines and think, Hmmm, Leo DiCaprio? There's something about him." Characters in every one of the book's eight stories are ... not afflicted, precisely; with one exception, their situations are too nearly taken for granted to be called affliction. But they're "living with" not only pre- and post-op gender adjustment but breast cancer, adultery, step-incest, alcoholism, orphanhood, widowhood, Holocaust survival and Parkinson's, sometimes in combination:

He shakes. Mostly at rest. Mostly when he is making an effort to relax. And sometimes, after we've made love, which he does in a wonderfully unremarkable, athletic way, his whole right side trembles, and his arm flutters wildly, as if we've set it free.

He is married, and not to the narrator, we learn in "The Gates Are Closing," after we've seen them making love in synagogue -- two lone parishioner-volunteers on an off-hours paint job. These two are long-term lovers, and know how to take advantage of circumstance.

Though Bloom's situations are striking, and not simple, her tone is often one of cool, deadpan explication as her characters rehearse their new realities to themselves: "Jess knows that Jane will want a cigarette before they go choose what kind of penis Jess will have." It's a tone that half-parodies all those TV-mag popularizations that have come to dominate how we learn about other people's differences and misfortunes. And yet the stories' interior rhythm itself suggests a swinging, headlong rush at a brick wall: They end so soon you've barely adjusted.

It isn't that Bloom thinks affect is detectable only in the cancer ward. She is a practicing psychotherapist, and the smallest movements of emotion -- emotional thought, too -- have been a specialty in all her fiction. When Jess's mother, Jane, watches Jess sunbathing two days before surgery -- "watches her, watches him, until Jess falls asleep, a lock of black hair falling forward" -- Jane's thought train is a high-definition EKG of quietly willed goodwill.

A woman who's been having chemo treatments catches herself time after time in her irritation at her well-meaning husband's sickroom incompetence, in her wish to say to him, "Do you think, would thinking at all lead you to believe that it would somehow please me to have you now be kind about my appearance?"

Bloom's voice soars when it hits the range that includes hostility. A woman whose baby was recently stillborn, on her first visit back to her college department:

A girl is waiting for me in the hall. I don't mind girls too much, and I can even feel sorry for them, since I know what's in store for them and they don't. When I was her age, I'd look at women like me with just that same disgusted disbelief. Their stomachs billowed out, their asses dragged, their hair hung in limp strands or was sprayed up into alien shapes. Why did they do that to themselves? They must all have been ugly girls and never recovered. But I was not an ugly girl, I put this young thing in the shade when I was her age. ... My body defied gravity, defined lush perfection. Peach juice would run out if I was bitten. I was fucking perfect for three years of my life, and not too shabby until the recent past.

It isn't until the sixth story, "Hold Tight" -- the shortest in the book, 10 pages narrated by a teenager whose senior year has just been ruined by her mother's last illness -- that we get a sustained, page-after-page run of pure, all-blanketing fury, and realize that in fact Bloom's theme throughout has been our reflexive, scattershot adolescent selfishness when faced with loss and grief not to mention our helplessness before the pathology of a near-Biblical ill will, in ourselves and others. The stories' outsize subjects have been Bloom's grateful, necessary occasions for getting to the outsize point.

In 1997, Bloom's one novel, "Love Invents Us," launched itself from a story in her first collection; the story was reprinted whole -- with merely a name change and minuscule alterations -- as Chapter 1. The poor, simple, pitiable girl of the story -- undressing for a middle-aged man so she can see his bedazzled gaze (until he realizes what he's been doing and the story abruptly stops) -- grew up in the novel. By the book's end, Bloom had razed pity. It's interesting to wonder which story she might choose here, should she do such a thing again. (There's "The Gates Are Closing," for instance, with its transgressive lovers, one of the often-angry ones, which gets still sharper later: "Hell, yes. A whole new Hallmark line: Happy Day of Atonement. Thinking of You on This Day of Awe.") Whichever story she picked, she'd surely take it far beyond anything resembling stereotype, except perhaps to the eye of the most unregenerate blind man.

Shares