One of the central questions of contemporary American Indian literature — indeed, perhaps the central question — is how to live in the floaty interstice between two cultures: one trampled and impounded, sequestered into arid corners, and the other, that of the tramplers, bigoted and unwelcoming. How to live, as Chickasaw poet Linda Hogan once wrote, with “your hands in the dark of two empty pockets.”

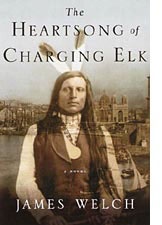

It’s the question N. Scott Momaday probed in his shattering masterwork, “House Made of Dawn,” and it’s one visited frequently in the work of Sherman Alexie, Indian lit’s most visible current exponent. It’s also a question that 60-year-old James Welch, a poet and novelist of Blackfeet and Gros Ventre descent, has been quietly brooding over for four decades now, most notably in the novels “Indian Lawyer” and “The Death of Jim Loney.” Now comes “The Heartsong of Charging Elk,” in which Welch poses that same question in more exotic terrain — in Marseille, France, where in 1889, history tells us, an Oglala Sioux named Charging Elk, hospitalized with broken ribs and influenza while on tour with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, found himself stranded after the show moved on without him.

Using that historical predicament for his springboard, Welch launches an ambitious, moving and altogether nourishing narrative of Charging Elk’s displaced existence following his abandonment. Charging Elk speaks neither French nor English, having joined Buffalo Bill’s troupe as a teenager only 12 years after his band of Sioux surrendered to the government, and thus he can’t explain to the nurses at the hospital who he is or where he belongs. He escapes into Marseille, hoping to find Buffalo Bill at the spot where he last saw him, but “there was nothing there,” as Welch writes, “not one sign that the Indians, the cowboys, the soldiers, the vaqueros, the Deadwood stage, the buffaloes and horses had acted out their various dramas on this circle of earth.” Arrested as a vagabond, Charging Elk is imprisoned, but with the aid of a splashy journalist, who makes the “Peau Rouge” a minor cause cilhbre, and the American vice-consul, he is released into the custody of a charitable family of fishmongers; his stay is supposed to be brief, but bureaucratic bungling weaves months into years. Flattened by loneliness and nostalgia, Charging Elk falls for the only woman who’ll seem to have him, a moody prostitute who betrays him to a fiendish gay chef with a yen for exotic-skinned lovers. More transpires — much more, actually, with less contrivance than it may sound — but eventually Welch returns to that essential question, forcing Charging Elk, in a moving if inevitable coda, to choose between past and present, between his old culture and his new culture, between what has been lost and what has been gained.

Welch’s novel moves with sensual grace — slow but never sluggish, and always seeming, with its plain measured cadences, to be building toward something, to be growing inside itself. Brief quoting won’t do it justice; Welch may be a poet, but “The Heartsong of Charging Elk” isn’t constructed with the kind of fevered language and punchy phrasings typical of what are considered “poetic” novels. Instead, the effect is cumulative, like a voyage across the plains: You don’t know the enormity of what you’ve seen until you’ve seen it all. What James Welch has produced, ultimately, is a novel with an expansiveness of heart and mind, an intimate analogue of Indian estrangement worthy of any readerly voyage.