Emmylou Harris has received highbrow press recently for the wrong reasons. The New Yorker and New York Times Sunday Magazine made a big deal of her small musical contribution to the forthcoming Coen Brothers film, "O Brother, Where Art Thou?" but scarcely mentioned Harris' new album, "Red Dirt Girl." It's her first studio record since '95. It sounds like a combination of Bob Dylan's "Blood on the Tracks" and U2's "The Joshua Tree." To hell with "O Brother, Where Art Thou?" "Red Dirt Girl" is a masterpiece.

The maestro herself sits at a tiny table in the basement bar of Rue 57 restaurant in midtown. She is dressed in black slacks and a purple top, with a dark Pashmina shawl wrapped around her shoulders -- it's cold down here, and outside it's storming rain.

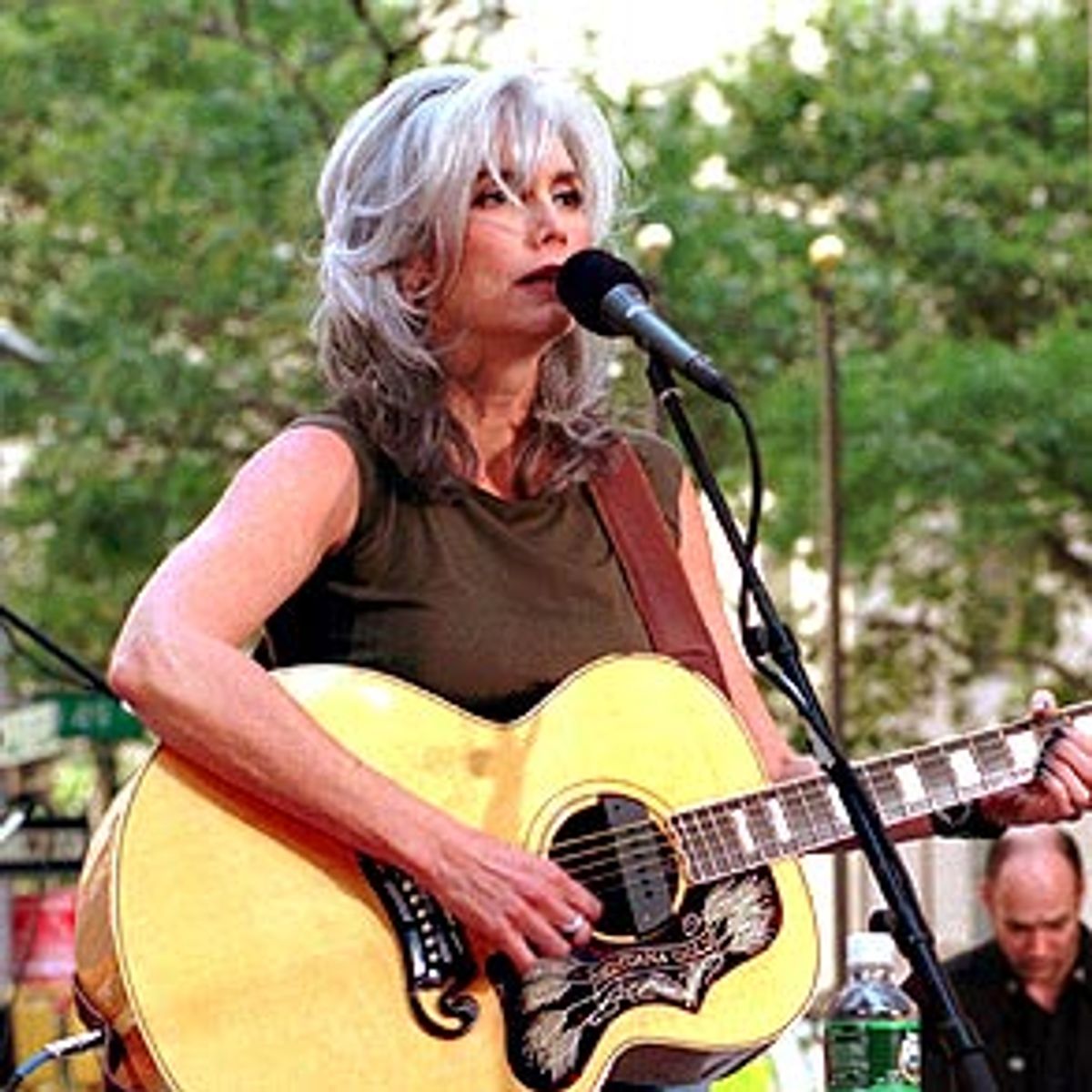

Harris is diminutive in body, and her hair is silver, gray and white. She is smoking a skinny brown cigarette. She doesn't lip the thing seductively, Dietrich style. Instead, she smokes like a woman on the run. This is the second time I've interviewed Emmylou Harris. The first time was five years ago in the lobby of Hollywood's iconic Chateau Marmont. She was sucking on some of those curious slender smokes then, too. She told me they were "herbal cigarettes." Five years later, when I ask her, "What are you smoking?" she says, "They're Indian. Bidis [pronounced Bee-deez]. I have a little tobacconist around the corner from me in Nashville."

A collegiate-looking waiter steps up. "You pay $3 a pack for those things," he says to Harris. "I used to get those all the time and they were only 99 cents. Now all of a sudden ..."

"I know," the singer says sadly. "But there are 25 in a pack."

"Is it hard keeping them lit?" the waiter mutters. He obviously recognizes the greatest country singer since Patsy Cline and wants to play out this moment as long as possible. "Mine go down all the time," he adds.

"I have a tornado lighter," Harris says with a devilish smile. "It will light in a tornado ... or a convertible."

I imagine streaking through the Tennessee countryside in a convertible with Harris, puffing on Turkish cigarettes. The nature of her cigarettes is not important, of course. I'm having lunch with her, not trying to do an exposi. After lunch, she's going to meet the New York Times' Daniel Menaker. Little does she know that he will write a hatchet job on her, calling her "the Queen of Remorse." She might as well be smoking her last cigarette before facing a firing squad.

Before I turn on my tape recorder, she complains about another hatchet job -- the one Bill Buford did on her colleague Lucinda Williams in a recent New Yorker.

"Even if Buford was telling the truth, he didn't have to write certain things," Harris says softly but emphatically. "He took license. He drew certain conclusions that were very one-sided. Hurtful to Lucinda. Detrimental to her person."

"What's the most extensive interview someone has done with you?" I ask.

She thinks a moment and tells me that she let a writer hole up on the bus with her for a tour of Europe. "During that tour I was sick and I had a terrible cold," she tells me. "He was writing a book. I came off as if my career was over and I was at death's door. I'd sunk so low in my life that I was living with my mother. It was a work of fiction." She pauses. "Do you know the book?" I nod. "What was it called?" I tell her. She frowns. "Don't give the title in the interview," she says, grabbing my arm. "Don't give him any publicity. Promise?"

I assure her I won't. When I first interviewed Harris, she seemed understandably aloof, like Greta Garbo playing the reluctant sovereign in "Queen Christina." Five years later, Harris seems vulnerable. "It's probably too soon to say this," I say, "but I think the new record is a masterpiece."

"Oh, I like this man," she says to the waiter, who is still lingering around the table. "I liked him when I first met him, but I like him even better now."

I ask for menus to get rid of the guy, then say, "'Wrecking Ball' was a collection of songs, but 'Red Dirt Girl' really feels like a complete album." I say, "Not to pigeonhole you -- for years you've been this ambassador for country music -- but 'Red Dirt Girl' is like a Lou Reed record."

"Thank you!" Harris says with enthusiasm. "This one is my own songs, so I suppose that's the biggest difference." She thinks a moment. "You know, being a songwriter is still kind of a new thing for me."

"How do you write a song?" I ask. (Dumb question.)

She shrugs. "It's a mystery." (The answer I deserve.)

"You've always had superb taste in the songs that you choose to cover," I say. "Does writing songs come from the same aesthetic place?"

"No. Totally different," she answers, "because all the work is done for you when you're singing someone else's song. All you have to do is find a key. Believe me, the looking is a whole lot easier than writing."

"Can you hear whether a song you wrote yourself is any good?"

"Oh, yeah. That's why it's so hard to write. It's specific and nonspecific. It's poetry. What's left out is as important as what's left in. You just know when it's right -- the same way that I know when someone else's song is good. I suppose that's my criterion. If I want to sing a song, it must mean it's good. Everything you write is not necessarily going to be good. That's scary because it's easy to discard a song by someone else, 'Whoops! I was mistaken. I don't like that after all.'"

"Do you have music always going on in your head?" I ask.

"No. I don't think so. You mean melodies?"

"Like a soundtrack to your life."

"No. I don't think it ever happens. I have to have a guitar sitting around. I sing in the shower. I sing around the house. The music comes secondary. The lyrics come first. The music of words. And the musicality of words that evoke images."

The waiter is back again. "What can I get you?"

I've avoided describing the restaurant because it has an innocuous, airport-bar quality about it. There are a few people milling around, caging drinks. Motown is playing on the sound system. The menu is vaguely French.

"I'm going to go with this grilled cheese sandwich," Harris says to the waiter.

Grilled cheese sandwich in a French bistro? Sounds good. I've never seen it rain so hard in the city. A grilled cheese sandwich and soup are good comfort food. "I'll have what she's having," I say.

The waiter departs. Harris continues: "'Wrecking Ball' reinvigorated me. And brought me into a new musical territory, but not terribly unfamiliar. I knew the only new thing I could bring to the table was my own material. My songwriting friend Guy Clark said, 'You need to write your next record, and I don't care if it takes you five years to do it.' Well, it did take me five years!"

"It's such an eclectic record," I say. Hypnotic guitars snaking above circus marches. It was produced by Malcolm Burn, protigi of Daniel Lanois, who in turn was a protigi of Brian Eno.

"Well, I've always been eclectic," she says. "You know, I'm a fan of Laurie Anderson. One of my favorite records is 'The Ugly One With the Jewels,' a spoken-word record. It's an extraordinary album. Brian Eno is doing all these sound things in the background and she is reading from, I think, her book 'The Nerve Bible.' It's all these songs that are eccentric but ultimately quite moving. Some of them just break your heart. It's very unusual. I never heard anything like it."

Harris lights another slender cigarette and continues, "If you're looking at an overview -- I definitely came in through the country door. It's like saying, 'Where were you born. What are your roots?' I was a folk singer who became totally over the edge with country music. I found my voice and style working with Gram Parsons. I learned how to listen to George Jones records and the Louvin Brothers. Listening to harmonies. Being enthused. I was a woman with a mission after Gram's death, trying to keep his music alive -- and bring what I liked about country music to people like me who came to it without growing up with it. Discovering the beauty and depth of it instead of the caricature." She shakes her head. "This politically incorrect music." She gives a laugh. "I really was on a crusade. Even from my very first record, I think I established a pattern of eclecticism. And I was hoping to encourage other people to go out and buy George Jones records. And discover the music that shouldn't be left behind. There was a power and beauty to it."

She sips some water. "Overseas there is no confusion. If I'm a country artist, whatever record I do is country. They don't pigeonhole it. Here the pigeonholing is rampant." She crosses her arms. "I never followed a pattern. If I had any kind of style it was no style. I could do a traditional record like 'Blue Kentucky Girl,' and people didn't understand it. So we went even further into the traditional with 'Roses in the Snow.' That's considered my 'country' record, but it's really my bluegrass record."

"As different as they are, 'Roses in the Snow' is like 'Red Dirt Girl.' They have the same hermetic feel."

"I think this was done with a small repertoire of people," Harris says. "We cut all these tracks with four musicians -- me, Daryl Johnson, Ethan Johns and Malcolm [Burn]. Except for me -- I always play rhythm guitar -- there was a revolving thing where sometimes Daryl would play bass and sometimes guitar. Ethan played drums on some things, but then would play guitar. Sometimes Malcolm would play keyboards. I love that."

"You weren't in separate booths or anything?"

"No. We recorded this album in Malcolm's house."

"Has technology gotten so you almost don't need a studio anymore?" I ask. As if on cue, Frank Sinatra begins playing in the restaurant. It sounds like something from the late 1950s.

She nods. "You don't need a studio if you've got people who know what they're doing and they're fearless." (Ha! You can bet Sinatra never recorded an album in any damn living room.) "There's bleed on everything," she continues. "We had a bit of a baffle around the bottom of the drums. We were just all sitting in the living room. We were live pretty much on everything."

"When you started working with Lanois, did you start listening to more electric things, like Laurie Anderson?" I ask.

"I've never just done acoustic," Harris says. "I love a blend of acoustic and electric. You have to explore all the different possibilities not only in your voice but in the things that excite you and pump you. 'Orphan Girl' [on 'Wrecking Ball'] was beautiful, almost generic-sounding, but the groove that Daniel came up with -- I didn't realize how much power that song was going to have for me, how inspired I was going to be through the actual process of singing. I got turned on. You're always getting turned on to different kinds of music. I've never just listened to one kind of music."

The waiter comes with our sandwiches. For some inexplicable reason, hers has a salad. She takes a bite and exclaims, "God, this salad is one of the best things I've ever eaten. It has really tart apples. And pecans."

My cheese sandwich is good. Who would have guessed the children of Robespierre could perfect Wisconsin cuisine? We're both silent a moment over our food. I then mention encounters I've had with Merle Haggard and Hank Williams' grandson. Both of these hardcore country musicians complained with bitterness of being squashed creatively by Nashville suits. "Do you have relative freedom from the Nashville establishment?" I ask.

"I don't have anything to do with the Nashville establishment," she says with determination. "It's a recording-industry, whatever's-gonna-sell kind of town. And there is this town underneath the town. It's songwriter based. Very creative. In Nashville you have Steve Earle and Gillian Welch, Lucinda Williams. And you're never going to hear them on country radio. I've always had the freedom to do whatever I wanted from the beginning. I lucked into that."

"I have this vision of Nashville executive wives with beehive hairdos," I say, "and little white purses around their wrists."

"Tony Brown [the king of Nashville] is an old friend," she tells me. "He used to play piano for me. We meet socially. He's a bright guy. I don't have anything to do with him creatively. But even Tony in the early days -- when he was first gaining power -- put out records with Albert Lee and Jerry Douglas. He was really trying to make a difference. So I don't know where the resistance to roots country is coming from. Radio blames the record companies. Record companies blame radio. You have all these millions of people buying the flavor of the month. It is what it is. Ultimately you have to have the courage to do what you want to do." She puts her fork in her salad, then leaves it. "I do want to say this: I think it's a shame that Merle Haggard would even have to complain. When I think about this man and what he has done and the body of work he has done and is still doing as a writer, as a bandleader, as a singer, the fact that he isn't on the charts is a travesty. There are new country music fans who don't even know who he is. Same thing with George Jones. That's just not right."

"Your new label, Nonesuch, is millions of miles from a Nashville label, isn't it?" I ask.

"I'm finding out that they are a bunch of people who love all kinds of different music," she answers. "They believe that there is life beyond radio. I believe Nonesuch signs the artists they believe in, not the ones that they think are going to sell 6 million records. I love what they did with the Buena Vista Social Club. I think they do things for the right reasons." Then she says, "This is fantastic," again about her sandwich.

I notice a plate of little white nuggets beside her salad bowl. "What are those?"

"That's to dunk in the soup," she laughs. "They're garlicky things and then you dunk them in the soup." She catches the waiter: "I think I'm finally done. I'll have a cup of coffee, please."

I choose this moment to ask the one personal thing I've heard about Harris. I know guitarist Chris Whitley, who in turn knows Lanois, the producer of "Wrecking Ball." Whitley told me Lanois and Harris were an item.

"I made a record with him," she says.

"Were you romantically involved?"

"No," she answers. "We knock around together a lot."

I drop it. The waiter brings the dessert menu. "Banana burrito," she says. "That sounds interesting."

She makes no move to order one. So I do.

"Are you a fan of anybody who intimidates you?" I ask.

She answers immediately. "Aretha Franklin. I met her once backstage." Pause. "She's just ... it."

"Do you still feel normal around Bob Dylan?" I ask. (She duetted with him on his mid-'70s album "Desire.")

"Does anybody?" Harris answers with a laugh. "I've only hung around with him when we were making a record. And one other time -- a TV show for Willie Nelson. I actually sang on that record they did for Jimmy Rodgers, and the track was already done. And he decided he wanted to re-sing it and I wasn't available to do the harmony." She pauses. "Boy, he's a tough one to sing with. You think it's the most convoluted thing. But then after you actually figure out what he's done, you realize the genius. His phrasing. What he does with a lyric is just astonishing. He comes up with things that are totally unique, and serve the song. It's not like he's showing off."

The coffee comes. The banana burrito as well.

"It's beautiful," she says, peering at it. "Lovely color."

It looks like a cross between a fish and a petal from a ginger plant. I push the plate toward her and hand her a fork. "Take a nip."

She doesn't. I feel like Satan tempting Harris, so I look away. Maybe she'll take a bite. "How conscious are you about your private life?" I ask.

"I avoid that," I hear her answer me. "What I have to offer to the world is music and my take on it. I'm not here to talk about my personal life. I find music so fascinating and am so completely obsessed with it, that really is what I'm like. That's what I end up talking about." I ask if she feels like she's carrying the torch for Parsons, who died among groupies and drugs in a Mojave Desert motel in 1973. "I don't know if that's still the case," she says. "He was my mentor. He was the person who I felt I was going to work with. And we were just beginning a musical journey together. That was a hard thing to give up. I didn't really know what I had to sing myself. It's been a lot of years now, a lot more things have happened. I've lived twice as long as Gram. That's an odd thing to think about. A lot of water under the bridge."

"How often does he come up in your head?"

"Oh, I don't know. Like anyone who's been important in your life, he becomes part of the fabric of your life. He's there. He's always going to be there as someone who shaped you. There are a whole lot of other things crowded in."

I sneak a glance at the banana burrito. She hasn't touched it. "I've always loved 'Sally Rose,'" I tell her, referring to her 1985 vinyl roman ` clef about Parsons. "Was 'Sally Rose' a disappointment saleswise?"

"It didn't sell many records, so it was a commercial disappointment," she answers, hunting for another of her slender Indian smokes. "But you know, it was just so amazing that I finished that record, that I actually set out to do what I said I'd do. I had to do that record for myself. That was a point where I had something to say. I had the bits and pieces. I had to finally sit down and complete it and go with it, whether anybody got it or not. I never thought of the record as a failure. It made me realize that one's career definitely has peaks and valleys. You have to surf them. If you just keep escalating on and on until infinity, you're not going to survive in this business."

I ask her if she has helped any of Parsons' biographers.

"No," she says quietly. "I was asked to once and I just thought I had my own history, my own take. I still have opinions forming on autobiography and biography. I'm not so sure I believe the books because I think there is so much fiction even in an autobiography -- even when you think you're absolutely telling the truth. It's very hard to say, This was who that person was. Even if you watched a video on someone's life from the moment they were born until their death, you still don't get the inner life, do you?" She pauses and adds, "I'm not saying that I won't ever do one, but if I ever did, it would probably be to counteract other things that have been written."

"Do you have to worry about your kids writing books?"

"I'm not going to worry about it," she says, lighting a Bidi. I can see the ghost of Cary Grant shaking his head at me over her shoulder. Should I have offered to light it for her? Humphrey Bogart appears along with Sydney Greenstreet wearing a fez. They both shake their heads. Dames like to light their own Indian cigarettes. "If my kids want to, they can write one," she continues. "But I don't think so. In fact they're very, very protective of me. They also are really sensitive about us being in a social situation, when everybody zones in on me and kind of dismisses them. And then they find out that these girls are my daughters, and all of a sudden they get attention. My kids just dismiss those people. It's not like, 'Oh, mom gets all the attention.' It's, 'That person is a jerk because they're being rude.' It's an interesting thing to see. My kids are pretty savvy. But they are very protective of me."

"How small as a small town is Nashville?"

"The smallest. But it's so small that it's very comfortable. In all the years I've lived smack-dab in the middle of Nashville, I've never had any of those tour buses drive by. For one thing, I'm not on the charts anymore, so nobody is really interested, which is great. And everybody is in the business and everyone is a songwriter. Even your plumber! My road manager, Bill, has this thing about, 'Are you an ASCAP plumber or a BMI plumber?'" I ask Harris if a plumber ever came to fix her sink and left a song. "I remember a plumber was doing some work and couldn't believe I was me. Finally he said, 'You mean, you're her?' So ever since then I have this whole thing about how I have to become 'her' -- 'I have to leave now. I have to become her.'"

"That's a great way to describe it," I laugh.

"I've always just thought of myself as myself," Harris says. "I don't do anything special. I know there are times when I'm buying groceries and if the sun is out, no matter what time of year it is, I wear sunglasses because I have very sensitive eyes. A lot of time I wear a hat because I like to put my hair up. Somebody will go, 'I know who you are. You're incognito.' You feel like saying, 'But I'm not!'"

Suddenly Italian music begins playing in the restaurant, as if this is the soundtrack to a Fellini movie.

"I don't have to ever worry about camouflaging myself," she continues. "I've never had that. I just don't elicit that in people. I'm not a household name. I'm not a star, you know what I mean? Gratefully, whatever normal is (besides being a cycle in a washing machine), I have that kind of life."

And with that, I signal for a check.

Shares