"Look scared. Look more scared," says a mother to her young son as he poses by an open grave in a cellar dungeon. The two are on a visit to the "Ackermansion," in the hills near Griffith Park in Hollywood, Calif.

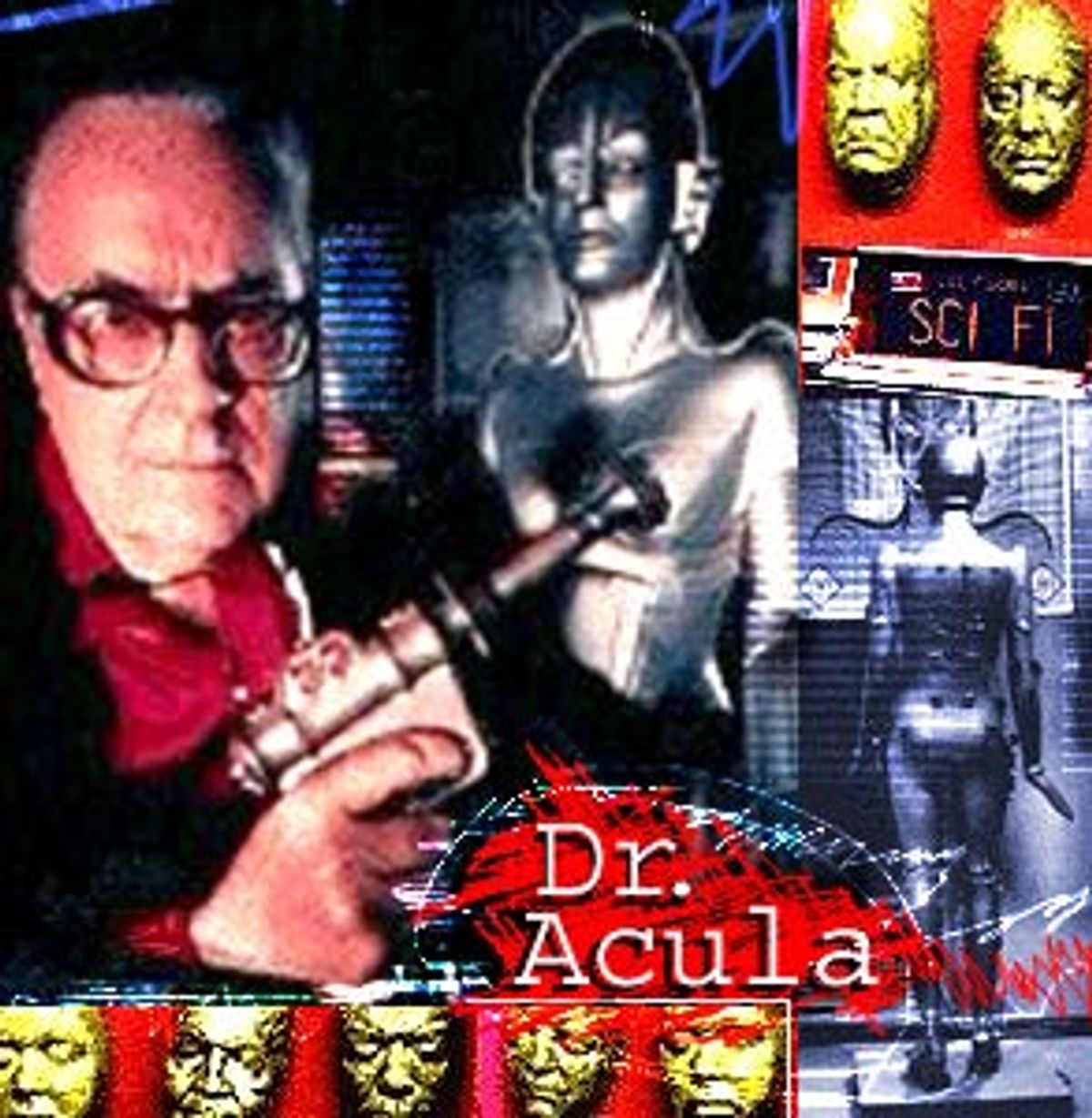

The proprietor of the Ackermansion is Forrest Ackerman, 84, otherwise known as Forry, as 4e or by his pen name, Dr. Acula. He has amassed the world's largest collection of horror and science fiction memorabilia -- more than 300,000 books, magazines, posters, paintings and relics of all kinds. Ackerman, who keeps the collection in his home, is a writer and editor who founded the original Famous Monsters of Filmland magazine, a literary agent who has represented Ray Bradbury, Ed Wood, L. Ron Hubbard, Isaac Asimov and Hugo Gernsback, and an unabashed fan who got to know the pantheon of horror greats: Bela Lugosi, Boris Karloff and Vincent Price. Ackerman has also inspired generations of writers and filmmakers including John Landis, Steven Spielberg and Joe Dante.

In the late 1950s when "hi-fi" was all the rage, Ackerman coined and helped popularize the term "sci-fi." He also managed to find time to create the buxom, bloodthirsty, red-vinyl-bikini-clad comic book heroine Vampirella. Says Spielberg, "Forry is a hero in his own time."

Ackerman's collection includes the ring worn by Lugosi in "Dracula"; the cape and suit Lugosi wore for the original Broadway production of "Dracula," which preceded the movie; German film director Fritz Lang's monocle; the top hat and teeth worn by Lon Chaney in his lost silent-film classic "London After Midnight"; a first edition of Bram Stoker's "Dracula," given to Ackerman by Lugosi and inscribed by Stoker and every actor to play Dracula in the 20th century; a piece of the Death Star model from the original "Star Wars"; a Tribble from the original "Star Trek" series; a gremlin from Joe Dante's 1984 movie "Gremlins"; Mr. Spock's pointy ears; Ray Harryhausen stop-motion models; and original models of the sexy robotrix from Lang's 1927 "Metropolis," which Ackerman has seen 93 times.

From floor to ceiling, the house is filled with the horrific and the sublime, the grotesque and the fanciful, and one begins to worry that someday the place will implode upon itself like Edgar Allan Poe's House of Usher.

On any given Saturday when Ackerman's in town, he opens his home and collection to visitors, and you're likely to find a small group of hipsters and geeks, fans and cognoscenti gathered at 11 a.m. outside the rather innocuous facade of 2495 Glendower Ave.

One young man, a first-time visitor, says, "I'm a virgin," and then after a moment of reflection adds, "I don't mean in that sense." The awkward silence that follows is disrupted by a metallic loudspeaker voice, "Leave the gate open for the next victim." A side gate is buzzed open that leads down an overgrown stairway to a back patio, where a dapper Dr. Acula meets his visitors. Ackerman, with his slicked-back hair and pencil mustache, looks like a cross between Martin Landau playing Lugosi in "Ed Wood" and Price in "House of Wax."

For connoisseurs of horror and science fiction, a visit to the Ackermansion is the equivalent of visiting Mister Rogers' neighborhood, albeit a nightmarish and fantastical version populated with aliens and vampires, plasma and bloodstains. "I've been doing this since 1951," Ackerman explains. "I've had 50,000 people visit me. A couple of weeks ago I had my first visitor from Tibet. Recently, a man and a woman helped celebrate their honeymoon by coming here," he recalls as he leads visitors into the basement rooms of his house, every wall covered with sagging bookshelves or memorabilia.

"It all started in October 1926 with one magazine, at the corner of Santa Monica and Western. This magazine jumped off the newsstand and grabbed hold of me. You're too young to know, but in those days magazines spoke, and this one said, 'Take me home little boy, you will love me,' and everything grew from this." Ackerman pulls the first issue of Amazing Stories from one of the overloaded shelves, the very issue that he picked up at age 9. "This is still my favorite piece in my collection," he says. On the wall next to his complete collection of Amazing Stories pulps is a painting that re-creates that first issue cover, into which artist Frank Paul has inserted a young Ackerman as a man in a spacesuit facing off a bug-eyed Martian.

The illustration is neatly emblematic of Ackerman -- who clearly wants nothing more than to insert himself into the different realms of fantasy that cover his walls and comprise his collection. One enlarged photo shows him sitting in George Pal's time machine with the inscription "For Pal's Pal Forry from Pal's Pal's Pal Ray [Bradbury]." Another photo shows Ackerman made up as Frankenstein's monster accompanied by a scantily clad lass. On his bedroom door, an 8-by-10 photo of Marlene Dietrich is inscribed "Congratulations Forry." For Ackerman, every piece of memorabilia is a fantasy realized.

As he crowds the visitors into a tiny room, he asks, "Did some of you see the film 'Ed Wood'? Here's a genuine flying saucer from 'Plan 9 From Outer Space.'" A UFO made of paper plates and cardboard dangles on a string from the ceiling. With a nudge of his finger, Ackerman launches the handcrafted spaceship into a wobbling circular movement.

"At one point I became Ed Wood's il-literary agent," he tells us. "He was talking about making a Bela Lugosi film, and I suggested that he call Bela Dr. Acula, and so he began giving me his short stories. I'm afraid for the most part he was just a drunken voice on the phone to me at 2 o'clock in the morning, babbling things that were incomprehensible."

In the center of the room, on a pedestal, is the last of the Martian saucer ship models from Pal's "War of the Worlds," a metallic manta ray with a head on a long stalk. In another corner sits a model of the pteranodon that tried to fly away with Fay Wray in "King Kong." Ackerman remarks, "I got it from the brother of Rod Serling and it arrived in a shoe box in the mail. I had to jump in the car and rush over to the first friend who would appreciate my treasure, but his wife came to the door and she didn't appreciate anything about pteranodons. She went screaming to her husband and said, 'I think Mr. Ackerman is here with a dead crow.'"

As we walk through the basement library, he points out 600 or so books about the lost city of Atlantis, and asks if we have ever heard of Esperanto. "There are 6,016 languages in the world and 2,000 people got the idea that we should start over again and make one so simple that everyone could understand it. I learned it when I was a kid." Like a sculptor, he reaches out and touches the chin of one of the young lady visitors, and in fluent Esperanto romantically expounds, "For example, regard this beautiful visage with the long brown hair, red lips, white teeth. What a beautiful visage." After he translates, the young woman blushes and says, "Thank you."

Twelve rooms later, the tour ends in the living room. Ackerman sits down in a wingback chair, his left hand -- with Lugosi's Dracula ring -- hanging over the armrest, and talks about Lugosi to the visitors who have gathered in a semicircle around him. "I was with Bela Lugosi just two weeks before his death, at a premiere in Santa Monica for his film 'The Black Sleep.' He was a very vain man and would not be seen in public with his glasses, so as we were coming down from the mezzanine everything was a big blur to him in the lobby, but I could see that they were all set up to interview him on TV. We reached the bottom of the stairs and I said, 'They want you there,' and he said, 'Point me in the right direction.' 'Take about six steps forward,' I replied, 'and you'll be there.' This was a minor miracle to behold. Here was this dear old man, who looked like a concentration camp case. He was drying out from the drugs he had to take for the incredible sciatic pains. The world wanted him one more time, and right before our very eyes this dear old man straightened up and filled out and became the tall proud figure of Count Dracula as he strode toward the waiting TV cameras."

On his right hand Ackerman wears Karloff's ring from 1932's "The Mummy." "Boris Karloff was making his final four films in five weeks down in a little hellhole in Santa Monica," he reminisces. "I don't know where they got the nerve to even call it a studio. But he would get directly out of the chauffeured limousine into a wheelchair, and he would have to sit with a tank of oxygen by his side, metal braces on his legs and half a lung, but he was such a consummate actor that some of us on the set, not being familiar with the script, almost ruined a scene. He was busy being the mad doctor working in his laboratory, and suddenly clutched his heart and fell against a wall so realistically that we really thought he was having a heart attack, and almost rushed in to give first aid.

"Fifteen years after Boris Karloff died," Ackerman continues, "Vincent Price was flying over to Rio de Janeiro to meet up with me for a Fantasy Film Festival, and he said during the night a middle-aged lady came to him and said, 'Could I have your autograph? I can't tell you how many years I've enjoyed your films ... Mr. Karloff.' So Vincent Price brought Boris Karloff back to life, the only autograph he wrote years after he died."

Ackerman can't stop. He tells about how he befriended a 17-year-old science fiction fan named Ray Bradbury and came to edit and publish his lifelong friend's first story in 1938. On another occasion, he met a young writer named L. Ron Hubbard in a bookstore and was to later represent the Scientology founder's early science fiction writings. Ackerman talks about acting as Basil Rathbone's sidekick in a low-budget film, seeing Isaac Asimov bite a young model on the bottom at a Fantasy Convention and getting a phone call from director John Landis late one night to come out and make a cameo appearance in Michael Jackson's "Thriller" video. At the end of the stories there is silence, and Ackerman says, "Well, gang, I'd be happy to autograph anything, have my picture taken, answer any questions you might have."

A young special-effects man from Venice Beach, Calif., shakes his hand, and says, "When I was growing up there was nothing else around ... Famous Monsters was it. It was wonderful to grow up with that kind of magazine." Another man presents Ackerman with a plastic foam tombstone upon which "Dr. Acula" is emblazoned in large letters.

A 7-year-old girl comes up to him and says, "I've never seen so much weird stuff before." Ackerman says, "I started out when I was 9 years old collecting all these things."

"How old are you now?" the girls asks.

"Eighty-four."

"That's old."

"Well, I'm heading for 100," he says, and the little girl walks away in awe.

An attractive brunet asks to have her photo taken with Ackerman, and he whispers to her, "You'd have to run from Isaac Asimov." As she walks off, a Dr. Acula fan says to her, "He likes you because you remind him of the model that Vampirella's look is based on."

On the baby grand piano in the living room there's a one-page original manuscript of a story, "The Killer," by Stephen King. I ask about it. "Thirteen-year-old Stephen King sent that to me. I held onto it and finally published it several years ago when I was reviving the Famous Monsters of Filmland magazine."

I ask if he has any plans for preserving his collection after he is gone. "I've been trying for 25 years to find a final resting place for all this. Over in Berlin, they were going to house the collection inside of a $42 million hotel, but when the Berlin Wall went down the economy went down. Right now, in Las Vegas, they're talking about building a hotel and wrapping up this whole house and moving it into it. If I were a vegetarian, I could've survived on the giant carrots that have been dangled in front of my nose for 25 years."

I have a couple of final questions before I leave. "Why?" I ask. Ackerman caresses his Dracula ring for a moment before replying. "If a man is dying of thirst in the desert, every drop of water is precious to him. And when I was 9 years old we didn't have pocketbooks and hardcovers and videocassettes. Each magazine was like a drop of water to a man dying of thirst, so I treasured them. I didn't know then that my collection would get to this point."

And with such a large collection, I wonder, what does he covet that he does not have? "Well," he answers matter-of-factly, "like everyone else, I'd like the bolts in Frankenstein's head."

Shares