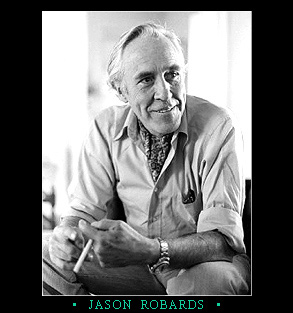

In the appreciations of Jason Robards that appeared when he died of cancer at age 78 on the day after Christmas, he was lauded as our greatest stage interpreter of Eugene O’Neill and the winner of back-to-back supporting Oscars for playing Washington Post executive editor Ben Bradlee in “All the President’s Men” (1976) and novelist Dashiell Hammett in “Julia” (1977). Apart from his brilliant replay of James Tyrone Jr. in Sidney Lumet’s movie version of O’Neill’s “Long Day’s Journey Into Night” (1962), I think he will be remembered on film primarily as our greatest interpreter of Jonathan Demme and Sam Peckinpah, in a pair of parts that together defined a rough-hewn and ornery kind of American heroism.

Robards got his third Oscar nomination in what remains Demme’s finest film to date: “Melvin and Howard” (1980). Bo Goldman’s screenplay took a story out of the headlines — centering on the purported Howard Hughes will that left Melvin Dummar, a young Utah gas station operator, one-sixteenth of the Hughes estate — and transformed it into a lyrical comic fable about the American Dream viewed from top to bottom. Demme and his cast, headed by Robards as Hughes and Paul Le Mat as Dummar, brought it off with sublime good humor, turning a slice of life into a piece of cake. In the opening sequence, Robards’ Hughes races on his motorcycle through the desert outside Las Vegas — a landscape that looks as barren and cratered as the moon. He’s rabidly gleeful, seizing on speed and motion as if they were his only remaining pleasures. Then he crashes, and takes on the aspect of a moon man who landed head-first in the desert.

Robards’ Hughes is an otherworldly figure not simply because he’s dazed, but also because he’s ferociously suspicious, selfish and cantankerous. Yet so potent is Robards’ acting that you still see Hughes’ vestigial humanity in the corner of his eyes; his facial expressions shift in layers, like the sand. When he stares askew at Le Mat’s goodhearted, open-faced Dummar, who doesn’t recognize him and wants only to rescue him, Hughes betrays his distance from the salt of the earth. Dummar gives Hughes a ride back to Vegas even though, woozy and bloody-eared, the tycoon looks and acts like the vilest drunken bum. And Dummar won’t let Hughes out of his pickup truck without befriending him first. He revs up the crusted emotions of Robards’ Hughes the way he would a stalling engine, and finally persuades him to sing a silly made-up Christmas song, “Santa’s Souped-up Sleigh.” Later Hughes will try to play Santa Claus himself.

The opening 20 minutes work as an incredibly funny-sad, democratic vignette of two dissimilar creatures finding their common feelings by joshing each other, and by savoring the perfume of sage and greasewood that permeates the desert air after a rainstorm. With a subtlety that verges on alchemy, Robards gradually shows us the cunning that made Howard Hughes Howard Hughes. Sizing up Dummar’s good nature, he milks the sometime milkman for his last quarter — the act of a dead reckoner and great dissembler.

Dummar thinks money can buy happiness or at least help it along. Hughes has left that notion behind. Robards sings “Bye Bye Blackbird” in a cracking, wavering voice, expressing a resignation beyond either bitterness or hope. Yet the animal purity of Le Mat’s Dummar cuts to the core of Robards’ Hughes and sparks his dormant sympathy. The movie is built on this portrait of two American individualists: an old man who’s lived out his wild fantasies and a young fantasist without portfolio — until Hughes leaves him one, in his will.

A decade earlier, for Sam Peckinpah, Robards had created a figure who was like Hughes and Dummar rolled into one. As the title character in the Western comedy-drama “The Ballad of Cable Hogue,” Robards falls out with two gutter-trash peckerwoods and is left to die in the desert. After praying to God for survival, he finds water “where it wasn’t,” and with the aid of two stage-drivers and an itinerant preacher proceeds to found a lucrative waystation. At the same time he falls for a lovely tart named Hildy. He loses her for a while to the lure of San Francisco, but she returns after Hogue has successfully left his mark on the land he owns and taken vengeance on his two former comrades. Cable is ready to leave his desert and go with Hildy, when, in a freak accident, her automobile runs over him. “Take Hogue,” says the bogus reverend to his God, “but do not take him lightly.” And with Cable dies his lifestyle and his land.

“The Ballad of Cable Hogue” may not be Peckinpah’s greatest film, but it is the one that most fully and persuasively expresses his bright side. Robards helped him turn Cable Hogue into an unexpectedly touching embodiment of all the frontier virtues that Frederick Jackson Turner once eulogized — not merely “that coarseness and strength combined with acuteness and inquisitiveness,” or “that practical, inventive turn of mind,” but, most of all, “that exuberance which comes from freedom.” There is no false pretense to Hogue’s life, only intense feeling and purpose. He is able to love a whore as a lady or befriend a frontier Elmer Gantry because they too are human beings who grab at any form, any facile imitation of love — out of their desperate loneliness. He lays down rules of commerce but won’t let them interfere with decency and joy. All he asks for is the basic American request to secure his own life, liberty and happiness. Hogue builds his own society — no, his own Eden. “The Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away” — and so does Cable Hogue.

Robards won more immediate fame and popularity for his depiction of Ben Bradlee as a newsroom swashbuckler in “All the President’s Men,” and for the paradoxical anti-glamour glamour of his Hammett in “Julia.” But I’ll remember him most fondly as an untutored Willie Nelson singing “Butterfly Mornings” in “The Ballad of Cable Hogue” and “Bye Bye Blackbird” in “Melvin and Howard.” This actor who seemed so much an urban character, with his dark, appraising eyes and eloquent saloon-bred hoarseness, leaped into another realm when he reverently raised the American flag in “Hogue” or blasphemously churned the dust in “Melvin and Howard.” He became an indelible frontier deity.