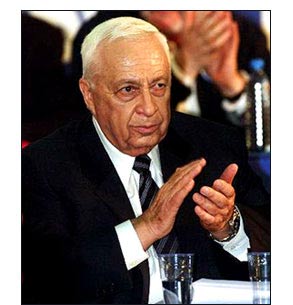

In a clear-cut special election that will warrant no lawsuits, no recounts, no interpretations of chads, an overwhelming 62.5 percent of voters elected Ariel Sharon, the veteran hawk, as prime minister.

The result, predicted for weeks now by Israeli pollsters, surprised no one. More intriguing was the success and scale of Sharon’s political comeback. Sharon’s victory comes 18 years after an Israeli government investigation found Sharon indirectly responsible for the Sabra and Shatila massacre, in which hundreds of Palestinian refugees were killed in Lebanon, and forced his removal as defense minister, crushing his political ambitions.

Also stunning was Ehud Barak’s snap decision to step down from the leadership of the left-wing Labor Party. Barak, a would-be peacemaker but hapless politician who charged on a perilous diplomatic path without preparing the Israeli public for the necessary concessions or taking into account Palestinian objections, first defended his record: “We removed not only the masks from the face of our rival but also the veils of illusion from ourselves,” he said in his concession speech.

Then, taking responsibility for Sharon’s knockout victory, Barak announced to the astonishment of his aides and audience that he intended to leave political life for a while. In this, he followed the example of his predecessor, Benjamin Netanyahu, who resigned as head of the right-wing Likud Party on the night of his electoral defeat in May 1999 in order to better prepare for his political comeback. “We have lost the battle, but we will win the war,” promised Barak. “In time we will return because our path is the only path, the path of truth, and in the end the truth will triumph,” he concluded.

Sharon’s victory and Barak’s brisk exit heralded the start of a heated political season in Israel. Sharon now has 45 days to establish a working government, based on an alliance between small right-wing parties or in a coalition with the left. The left, disoriented by Barak’s defeat, will seek to elect a new party chairman while settling personal scores. Meanwhile the Knesset, Israel’s fractious parliament in which Likud and Labor — the two major players — control only a third of the seats, must adopt a 2001 budget by March 31. Failure to establish a government or pass the budget within legal deadlines would trigger new elections. No wonder, then, that Israelis showed so little enthusiasm for Tuesday’s race. Voter turnout was meager, falling to a record low of about 59 percent.

“I don’t want to vote and I don’t care,” announced Ruthi David, a primary school teacher in a purple tank top and sequin-studded sunglasses who was strolling down Shenkin Street, Tel Aviv’s answer to Miami’s South Beach, on Tuesday. “I voted for Barak last time but I was disappointed by his attitude and his politics so I won’t support him again. Anyway, the government will fall in less than a year,” said David, 24.

Since the 1992 adoption of a direct election law, Israel has elected members of the Knesset and the prime minister in separate elections. As a result, political life has become increasingly volatile and governments short-lived.

The unprecedented abstention rate was partly the result of a widely observed Arab boycott. Although Israel’s Arab minority handed Barak 95 percent of its votes 21 months ago, more than 80 percent of Arab voters stayed home this time around. By avoiding the polls, they voiced their frustration with Israeli politics and their anger at Barak, a prime minister who first ignored them and then allowed his police forces to turn guns against them, killing 13 young Israeli Arabs in last fall’s riots, including 17-year-old Asel Asleh, an Arab-Israeli peace activist.

But in a country where Arab voices rarely matter, Israeli pundits the day after the elections were mainly busy analyzing Sharon’s victory: The electorate has spoken — but what did it mean to say?

On the face of it, Sharon’s mandate is clear: He was elected to restore Israel’s peace and security in the wake of four-month-long clashes between Palestinians and Israelis. (Ironically, the violence that has killed so far more than 360 Palestinians and over 50 Israeli Jews began at the end of September, after Sharon paid a controversial visit to a Jerusalem shrine.) Repeating his campaign mantra, Sharon announced in his victory speech at a convention center in Tel Aviv Tuesday that his government would “work to restore security to citizens of Israel and achieve true peace and stability in the region.”

Tuesday’s vote, however, was as much a repudiation of Barak’s aloof and erratic style of governing as a vote in favor of Sharon. “Even a broom would beat Barak,” Limor Livnat, a right-wing Labor Knesset member, pithily observed. Moreover, the misgivings voiced both on the left and on the right showed that many Sharon voters were unsure of what kind of policy package they would be getting.

Throughout the electoral campaign, Barak’s team tried to paint a vote for Sharon as a vote for war, digging up his warmongering past, predicting that gas masks and rolling tanks would make an appearance the day after a Sharon victory and even mailing fake draft orders to tens of thousands of Israelis to bring them to their senses. “Don’t forget it’s important to vote,” droned a recorded woman’s voice from a megaphone mounted on a slow-moving car in Tel Aviv, traditionally a bastion of left-wing sentiment. “It’s a choice between war and peace.”

But at a time when roadside shootings, suicide bombs and sniper attacks have become regular occurrences, Barak’s message did not stick. For many Israelis, the country was already at war, and a comprehensive peace deal giving armed Palestinians more West Bank land and a slice of Jerusalem suddenly appeared a distant — and possibly very dangerous — dream. In the minds of most Israelis, the race then was not about Sharon’s past as an adventurist general and the possibility of a future regional war, but about the failure of the Oslo peace process championed by Barak.

Even Israelis who were prepared to follow Barak in his bold steps toward peace last summer found his diplomatic efforts difficult to accept by the fall — when the Palestinians launched an uprising — and downright scandalous after Israeli soldiers were lynched by a Palestinian mob and Israeli civilians started dropping dead on a weekly basis.

An editorial in Ma’ariv, one of Israel’s leading newspapers, called Israel’s sizable mood shift “the shattering of the Oslo dream. The size of the illusion matches the size of the disappointment.”

That feeling of deep distrust, present all along in the extreme right, is new among mainstream Israelis and key to understanding Sharon’s victory. According to Ruth Gavison, a political analyst at the Israel Democracy Institute in Jerusalem, in 1996 when Shimon Peres was narrowly defeated by Netanyahu “there was a feeling that an Oslo process type of move could bring a comprehensive end to the conflict.” In 1999, after Netanyahu brought negotiations with the Palestinians to a near standstill, “the feeling was that we didn’t do enough to see if that route is viable,” she said. “In 2001, the feeling is that it’s not clear if there is a way to reach a resolution.”

An annual survey conducted by the Israel Democracy Institute, in which people are asked whether they think a peace accord would end Israel’s conflict with the Palestinians, showed a huge drop this year in the confidence of Israelis in such an accord. “Electors feel that the track that Yitzhak Rabin and Barak took is leading to an agreement that will mean many concessions but no end of the conflict, plus a serious loss of personal security. They don’t like this deal,” said Gavison.

“Oslo is dead,” Sharon announced a few weeks ago — and it is with this dead legacy that Israelis expect him to deal. With Israelis getting killed every few days in terrorist incidents and the world community breathing down his neck to put an end to Palestinian suffering in besieged towns and villages, Sharon will not have the luxury of turning his back altogether to peace negotiations. As Nahum Barnea, a prominent Israeli political commentator, said, “The peace process is not a dog. You can’t put it to sleep.”

This is where Sharon’s problems begin. Thanks to a deliberately fuzzy election campaign, the proportion of people who expect Sharon to make compromises in dealing with the Palestinians is almost equal to those who expect he will not do so. In his victory speech, Sharon seemed to give reason to the first group: He called on the Palestinians to abandon the path of violence and return to dialogue, while pointing out that peace would require “painful compromises” on both sides. But Sharon, at the head of a party that commands only 19 votes in the 120-seat Knesset, may not have much room to maneuver if his political options are reduced to forming a strictly right-wing coalition.

The words of Nadia Matar make that clear. Matar, a settler in the Israeli-occupied West Bank and co-chairwoman of a hard-line organization called Women for Israel’s Tomorrow, which vehemently opposes the land-for-peace formula defined in 1993 at Oslo, warns that the extreme right would not hesitate to bring down Sharon. “We’ll make sure that any wrong move toward the left will bring down the government,” says Matar, who also fought to topple Netanyahu after he signed a U.S.-brokered agreement at the Wye Plantation in 1998 that promised Palestinians control of an additional 13 percent of West Bank land. “I’m not loyal to a person. I’m loyal to ideas,” Matar says.

The consensus view is that a unity government bringing together the Likud, Labor and a smattering of centrist, secular and immigrant parties is more likely to buy Sharon political stability than a narrow right-wing coalition. It would provide Sharon an “important safety net,” said Arye Carmon, head of the Israel Democracy Institute, if and when Sharon decides to adopt a moderate foreign policy.

Judging from the few issues Sharon stressed during his otherwise tight-lipped campaign, Sharon will try to redefine Israel’s negotiation positions around three main ideas: no division of Jerusalem, no land concessions in the Jordan Valley and no right of return for Palestinian refugees to Israel proper. “Sharon’s message in this campaign was that he would restore Israel’s center,” notes Yossi Klein-Halevi, a right-of-center Israeli journalist in a phone interview. “And Israel’s center, before Barak destroyed it, was based on these three points,” he says.

Others beg to differ, and they predict Laborites will have a hard time joining a unity government based on these limited diplomatic guidelines. “With a united Jerusalem, with the Jordan Valley and particularly without moving a single settlement, peace can perhaps be made with the Likud’s Central Committee, but not with the Middle East,” wrote Hemi Shalev, a political commentator, for Ma’ariv recently.

Sharon’s post-Oslo peace recipe could be a recipe for protracted war, given that even Barak’s far-reaching concessions at Camp David last summer were judged insufficient by the Palestinians. But Sharon’s red lines could also be simply clever opening bargaining positions in the Middle East peace bazaar. “Barak promised them too much, too quickly,” said Nir Fayna, a Sharon voter, on Tuesday. “In the end Sharon will give them the same thing but he will negotiate like a tough guy.” Others predict Laborites will have a hard time joining a unity government based on these stingy diplomatic guidelines.

Peace optimists noted, however, that while Sharon repeatedly promised during his campaign not to force settlers out of their homes, he refrained from making a single campaign visit to settlements, whether in the West Bank, the Gaza strip or the Golan. Sharon’s victory is “not a vote of confidence in the settler movement,” said Klein-Halevi.

Sharon has demonstrated instances of pragmatism and ideological flexibility in the past. One of the chief architects of Israel’s settlement policy, Sharon allowed the army to evacuate Yamit, a Jewish settlement in the Sinai, after Israel signed a peace treaty with Egypt in 1979. So it is not inconceivable that he would dismantle isolated settlements to meet some of Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat’s demands.

“He can act tough, he can play tough — he can be anything. That’s the main point about Sharon. He destroyed Yamit and he destroyed Kibya [a Palestinian village leveled in a commando raid in 1953]. He can move in all directions,” said Avishai Margalit, a political philosopher at Hebrew University.

The question now is who will join Sharon’s government and steer his legendary drive. A unity government depends in part on whether Labor will come out intact of the dog-eat-dog session inaugurated by Barak’s downfall. There are reasons to fear it may not.

Even before electors voted Barak out of office, the left’s unity was mined by castle intrigues. Part of the left spent most of its energy trying to persuade Barak to step aside and make room for Peres, the former prime minister and Nobel Prize winner because he fared better than Barak in the polls. Radical leftists even advocated casting blank ballots to help drive Barak out of office. And there are at least four contenders for the Labor Party’s leadership.

And it was the echoes of the left’s deep internal turmoil that resounded on Tuesday night. Israeli television quoted Yossi Sarid, education minister in Barak’s government, as saying that “Shimon Peres is almost the No. 1 reason for the failure tonight — he’s totally irresponsible.” Peres sounded bitter too: In a comment attributed to him by Israel’s Channel 2, Peres reportedly blamed a “stupid left” for allowing “Mussolini” to take power. But judging by the way Israeli politics move, Peres may soon be seconding Sharon.