The 19th century French decadent Octave Mirbeau once wrote that the only thing more mysteriously attractive than beauty was corruption. Were Mirbeau around today, he'd probably smack his lips at British director John Boorman's latest film, "The Tailor of Panama." Based on the bestseller by John le Carri, the picture revels in the seedy, humid orgy of Panama in the late '90s and the various international intrigues surrounding that country's famous canal.

Boorman's playful dip into the tropical fleshpots is greatly assisted by a cast led by Pierce Brosnan as MI6 operative Andy Osnard, a scheming, avaricious scalawag hornier than Brosnan's Bond and lacking 007's redemptive patriotism. British intelligence assigns Osnard to the Panamanian backwater as punishment for his sins. Once there, he enlists expatriate ex-con Harry Pendel (Geoffrey Rush), a tailor to Panama's political elite, in an effort to destabilize the country and enrich themselves in the process. Along the way, Brosnan's whiskey-swilling Osnard attempts to screw every female in the land, including Harry's wife, Louisa, played by Jamie Lee Curtis.

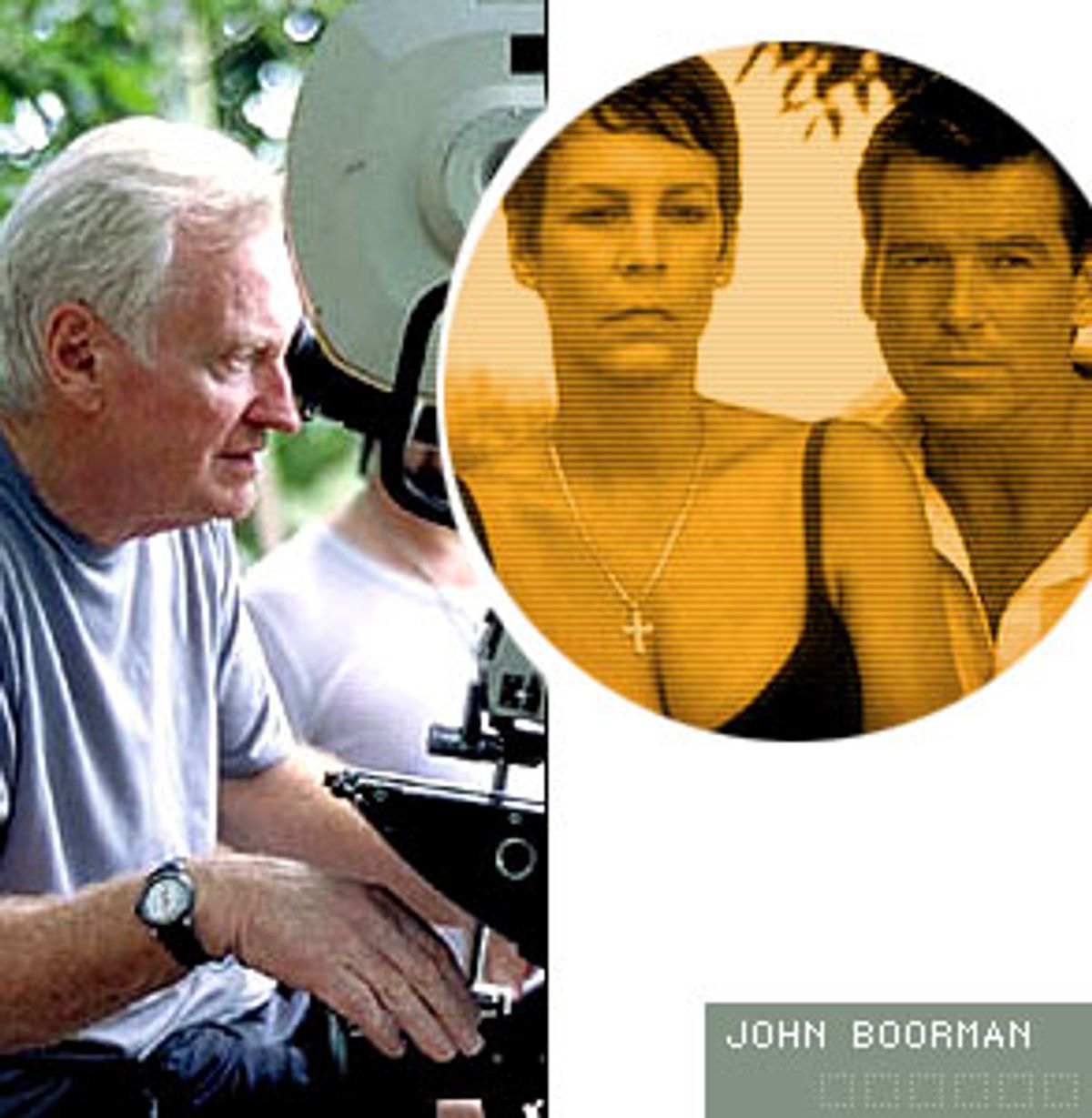

With generous dollops of black humor and sterling supporting performances from Leonor Varela, Brendan Gleeson, Catherine McCormack and playwright Harold Pinter as Pendel's Uncle Benny, "The Tailor of Panama" serves Boorman's legend well. The 67-year-old creator of such films as "Deliverance," "Excalibur," "The General" and "Hope and Glory," is a mercurial, entertaining personality who recently sat down to discuss the glories of Panama's whorehouses, J.R.R. Tolkien and one psychotic's contribution to the Oxford English Dictionary, among other things.

Spoiler alert: Boorman also discusses the ending of "The Tailor of Panama" at length in response to the sixth and seventh questions, which are on Page 2.

How close is the Panama you filmed in to the Panama of le Carri's novel?

You know, the book was translated into Spanish and widely read there. So I encountered quite a bit of hostility from the Panamanians because they were wounded by this description of them. More so because it was closer to the truth than they would like. But what I found there is what's in the film. Which is: Panama City is a money-laundering, drug-running place with all these banks that's totally corrupt. And their canal is this vital gateway. It's a very steamy mix. Also, it's the brothel capital of Central America.

For that brothel scene where Harry [Rush] goes to see Osnard [Brosnan], we were shooting in this hotel. There was a young Panamanian who was helping us, and he said, "My uncle's got a chain of brothels. I can get you any number of whores you want." So I said, "OK, I'll need about 24." Then I went to the hotel and told them what we were up to. They said, "We have whores. What's the matter with ours? Why do you have to bring others in?" It caused some bad feelings there, so I compromised. I brought 12 in and used 12 of their whores. That's Panama.

Were there really vibrating beds and hardcore porno on the tube, like in the film?

No, I added those things. All these scenes were about finding settings where Osnard can put Harry at a disadvantage. He's torturing him. So he takes him to that hotel or to that gay disco, settings that make Harry feel uncomfortable.

The Irish press reported that you were enraged with your crew because they were spending too much time in the bordellos. Did that really happen?

That was a very unfortunate remark of mine. It wasn't the film crew itself but the construction crew. They were painters and carpenters -- some of them had never been out of Ireland in their lives. Suddenly, they're in this place where all these things are possible. I went away, and when I came back, they hadn't progressed as much as I'd hoped because they'd been expending some of their energies on visiting these houses of ill repute. But it's kind of tricky because their union is threatening to sue me over this. Some of these fellows got in trouble with their wives. So I regret saying that very much.

What draws you to a scoundrel like Osnard?

That's the thing, Osnard is a totally reprehensible character, and yet, you kind of like him. He's got a certain charm. That's largely due to Pierce himself. Both Osnard and Harry are strangers in a strange land. Le Carri says these spies, particularly British espionage -- which has a long history because the British Empire was controlled by spying -- have nothing left to spy on. Even the Cold War's gone. They're just treading water. So they produce that sort of self-involved character like Osnard, who's out for whatever he can get. And he's delighted to find out some information, true or not, that he can impress his superiors with. They want something good enough to earn a seat at the table with the Americans.

Le Carri was himself a spy, and he was recruited very young. He said it destroyed his relationships because he couldn't confide in anybody. These spies are posted to these places, and they become isolated and disassociated. So here's this spy that's lost. And then here's this other guy who's reinvented himself and living a lie. What Harry can do is weave these stories and invent things. They become very dependent on each other. Their relationship becomes kind of important to them because they have this secret knowledge. It's almost like a seduction, like they're having an affair.

What was it like working with le Carri on the screenplay?

He wrote a first draft of the screenplay, which was full of vitality and fascinating things, and I did subsequent drafts and worked from the book. We only met a couple of times. He's a marvelous man. Tremendous mind. Very witty. A great raconteur. We had a terrific fax relationship. I would write a scene and send it to him, and he'd scribble notes on it and send it back. That's how we proceeded. He's been unhappy with previous film adaptations of his books, and they're not easy to adapt. Very complex. Great galleries of characters. Subplots. They work by an accumulation of details. Tough stuff to put on film.

When we were at the Berlin Film Festival with the film, at the press conference, he was asked, "What's the process of adapting a book into a film?" And he said, "It's like turning a cow into a bouillon cube." I thought it was a great metaphor because in a sense, the bouillon cube does contain the essence of a cow.

That said, how faithful is the film adaptation to the novel?

I think it's faithful to the characters and the basic situations, but the ending is very different. The book came out before the Canal was handed over to the Panamanians. It postulated a situation where the Americans did what they did to Noriega -- took over the Canal to prevent it from being given away. They bomb Panama. And at the end, Harry's so filled with shame and self-disgust at what he's wrought, that he walks into the flames and immolates himself. I felt I couldn't get to that point in the film. It was too apocalyptic. So I pulled back and had Harry shooting Osnard. We actually filmed that. And when I put it together, even that seemed too heavy a solution.

It trivialized that big scene where Harry confesses to his wife, because he's just killed somebody. So I reshot it so Osnard escapes. The tone of the film is that the bad guys get away with the money. For me the turning point for Harry, and the film, is the death of his friend Mickey. Harry feels responsible for Mickey's death. And that's the point at which he says, OK, I'm going to tell the truth now. He tries to tell the truth, but no one wants to listen to him. His life is in ruins, which is more interesting than having Panama in ruins. And when he tells the truth to his wife, it redeems him.

Was that a decision you made as the director?

Yeah. I felt that I'd gotten to a false point there. The other thing I changed had to do with an audience preview we had out in the San Fernando Valley -- the "killing fields" of movies. They recruited people by asking, "Do you want to see Pierce Brosnan playing a spy?" They were expecting a quasi-Bond film, and it colored the whole way they looked at the film. It didn't get great scores. That's when I realized that I was going to have to make it clear at the beginning of this film that he was a bad guy. Then I shot that scene at the beginning where he's sent off to Panama. You get the notion that he's this disgrace. That solved that problem along with a few tongue-in-cheek references to the whole Bond thing.

Is that a humbling process -- having your film test-screened?

It was horrible, just ghastly. Then they get a focus group together to tell you all the things you did wrong in making the picture. I do think it's dangerous the way studios slavishly follow whatever the scores are. But previews can be helpful. In this case, it defined a problem, and we solved it. In Berlin, we showed it on a big screen to an audience of 2000 people, and they embraced it. Everything was fine, but a lot of films have been completely abandoned after not doing well enough in previews. In a way, it gets the executives off the hook because they don't have to make a decision or commit to a film. They just think, "It didn't score well; let's dump it."

How intimately were you involved in the casting of this picture? Obviously having Pierce Brosnan in the key role gave the whole thing a sense of irony it wouldn't have had otherwise.

I started out with Geoffrey because that's a deceptively difficult role. He's playing a man who's playing a man. And it couldn't look like acting. We needed a very solid core to this character. Then the studio said, "We don't think he's enough to carry the film. We need someone in the other role." I came up with Brosnan. I could see the dangers of that, and so could Pierce. He was trampling on his image in a way. Those were the only roles that the studio was interested in having an opinion about. There were just a couple of others to cast, including Brendan Gleeson, who was in "The General."

I wanted to ask you about "The Lord of the Rings." Were you planning to do a live-action version of the trilogy in the '70s?

Yes, I spent a year on it. United Artists owned the rights. And at the end of the day, when I was ready with it, UA had gone into a very bad period. They didn't have the money. It was expensive, you know. For a while, I got Disney interested in doing it. But it languished there as well. Then I told Tri-Star I wanted to do it. The rights then were with Saul Zaentz, who produced the animated version. I was authorized to offer him a million dollars for the rights. He wanted more, but Tri-Star wouldn't pay any more.

Is it true you were so distraught over it that you could never watch the animated version? And how do you feel about the Peter Jackson film due out this year?

Yes, that is true. I never watched the version animated by Ralph Bakshi. As for the Jackson epic, I think it was a brilliant idea to make three films. Fundamentally, what had happened for me is that I made "Excalibur." Everything I learned, the technical problems I had to resolve in planning for "The Lord of the Rings," I applied to "Excalibur." That was my recompense. I'm glad "The Lord of the Rings" is being made now, and I'm looking forward to seeing it. I'm sure it'll be a big success.

Did you ever meet J.R.R. Tolkien?

I didn't meet him; I corresponded with him. He was reluctant to have a film made of it at all. It was only to secure the education of his grandchildren that he agreed to sell the film rights. He wrote to me and asked me how I was going to make it -- live action or animation. And I told him I was going to make it with actors. He wrote back, saying, "I'm so relieved, because I had this nightmare of it being an animated film." And of course, that's what happened. But he was dead by the time an animated film was made.

I know you corresponded with James Dickey regarding "Deliverance." Do you often do that -- correspond with your collaborators?

Not really. The problem with Dickey was that he was such a drunk. Whenever we met, he'd get very excited and terribly soused. You could never get a sensible word out of him. We had great times, but it wasn't helpful to the script. So we did a lot of it by correspondence. I'd send him a comment and he'd send it back. It was marvelous. But in person he was just a mess.

I remember I brought him out here to L.A. with me to work on the script, and he was holed up with this dancer. I couldn't get him out of his room for three days. We finally go back to Atlanta, and on the plane, he falls straightaway into an alcoholic sleep. About an hour later, he came awake, and he says to me, "If I wasn't a famous poet and a Baptist, I'd divorce my wife and marry the dancer." [Laughs.]

Will your next film be about the making of the Oxford English Dictionary?

Yes, I've just done a script on it, The Professor and the Madman." This Scot named James Murray was the editor. He was an autodidact with no formal education. But he spoke 20 languages fluently, and he was the only guy who could do it. Even though all these Oxford dons were horrified that they had to turn to someone who was academically unqualified. The other guy who helped him was an American surgeon who had gone crazy, killed someone and was locked up in an asylum for the criminally insane in England. He became the most important contributor to the book, and no one knew that he was a murderer and a madman. They had a great relationship, these two, and eventually James Murray got him released. Mel Gibson's company is making it, but we still don't know if he's going to play one of these characters.

Most of your films tend to deal with the world of men and what it means to be a man. Why is that an important theme for you?

Because I'm a man. We live these very comfortable kinds of lives where we're cut off from nature to a large extent. I think it's the cause of neurosis if you're not in touch with nature. There's a danger that you become disassociated, and I believe it causes a lot of our problems. So I'm always compelled to set myself challenges in relation to nature, to put myself in touch with nature by sleeping out in the forest, swimming in rivers or going out to make these movies and testing myself.

Shares