The United States Commission on Civil Rights released its draft report on last fall’s Florida presidential election at a plodding but contentious hearing on Friday. The atmosphere ranged from touchy to openly hostile, as the eight commissioners chewed over 200 pages of drainage from the Florida Election Day swamp without anyone making a clear case for or against the notion that African-American voters faced intentional discrimination on Nov. 7.

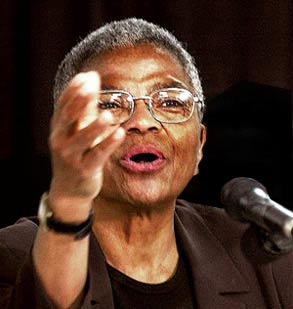

Like all things related to the presidential election in Florida, the meeting quickly divided into an acrimonious debate between Democrats and Republicans , and those who believe in a Florida conspiracy and those who don’t. While stopping short of saying there was a racist conspiracy to keep out black votes, Commission Chairwoman Mary Frances Berry, a registered independent, said the report shows the general sloppiness of the Florida election system had a “disparate impact” on African-American voters, and called on the Department of Justice to investigate further.

Contradicting Berry, and the report, at every opportunity was Abigail Thernstrom, the sole registered Republican on the commission and the first commissioner appointed by President George W. Bush. Thernstrom slammed the document for being full of politically charged rhetoric and broad assumptions of injustice with little statistical backup.

And she had a point. Along with the pages of personal stories collected from commission hearings in Florida shortly after the election, the report includes sidelong swipes at Harris and Bush. For example, in the chapter titled “Responsibility Without Accountability?” the panel takes issue with Gov. Jeb Bush’s testimony that county election supervisors were ultimately responsible for logistical problems that plagued the voting. That might be a cop-out, but the report sneers, “Under the Florida Constitution, the governor is charged with ensuring that ‘the laws be faithfully executed.’ Governor Bush apparently delegated the responsibility to ensure that the election laws are faithfully executed.”

The report also promiscuously employs terms like “several” or “many” when trying to account for the number of victims of all races who were locked out of the polls by the foul-ups in Florida. In describing the problems encountered by disabled voters, the report states that “numerous [disabled] Florida residents encountered obstacles to polling precincts and were thus disenfranchised.” Whether that “numerous” means tens, hundreds or thousands of voters, the report gives no clue. In another chapter, the panel describes “countless” would-be voters who arrived at polling stations and found their names missing from the rolls.

Perhaps in an attempt to account for the dearth of hard numbers about just how many voters were lost to barriers of language or access, missing registration information and bad communication between state election offices, Chapter 9 of the report claims, “Perhaps the most dramatic undercount in Florida’s election was the nonexistent ballots of countless unknown eligible voters, who were turned away, or wrongfully purged from the voter registration rolls by various procedures and practices and were prevented from exercising the franchise.”

There were more specific figures in the report concerning the numbers and races of people bumped off the voter rolls by Florida’s reliance on felon purge information provided by ChoicePoint, a Texas data analysis firm, claiming that more than 51 percent of those incorrectly scrubbed off the voter rolls were African-American.

Blaming a “lack of leadership” by Florida state officials, the panel also concluded that the state provided an inadequate education for poll workers and voters, denied proper access to disabled individuals, failed to outline proper procedure for handling disputed voter registration, did not provide language help for non-English speaking voters and carelessly purged the voter rolls based on a faulty list of “felons.” The report surmised that these factors led to “widespread voter disenfranchisement” that Berry said “fell most harshly on the shoulders of African-Americans.”

The panel’s majority made its strongest statistical case about racially disparate outcomes in its review of Florida’s 170,000 spoiled ballots, 107,000 of them “overvotes” where more than one candidate had been selected, and 63,000 “undervotes,” the notorious dimpled, hanging or pregnant chad ballots which registered no vote at all.

For this, the panel’s majority brought in outside help. Professor Allan Lichtman, chair of American University’s department of history and a veteran voting rights lawyer, provided the commission’s statistics about the disproportionate effect of voter disenfranchisement on African-Americans. “I came to this as a skeptic,” Lichtman said. His aim, Lichtman said, was simply to answer the question “Were there differences in the rate at which ballots were rejected by African-Americans and non-African-Americans?”

Lichtman’s answer was a resounding “yes.” He concluded that 14.4 percent of the ballots cast by Florida’s African-American voters were rejected, compared to a 1.6 percent rejection rate for non-blacks. He reached those conclusions by studying the rejection rates in predominantly black precincts of Dade, Duval and Palm Beach counties, which accounted for 47 percent of bad ballots. While Lichtman refused to say that African-American voters were disenfranchised as a consequence of their race, he did say that “there is a relationship here that is suggestive of a strong relationship between the racial composition of counties and the percent of rejected ballots.” At one point, Lichtman suggested that up to 54 percent of all spoiled ballots cast in Florida came from black voters.

Thernstrom wasn’t having any of that. “I have serious concerns about your methodology,” she said, sparring good-naturedly with Lichtman, a longtime associate whom she spoke of in friendly terms in the hearing. That didn’t stop her from slamming Lichtman for failing to study factors other than race, like education and voting experience, that she believed could have resulted in high numbers of faulty ballots. Though he acknowledged that he hadn’t studied those factors, Lichtman stood by his assertion that race was the common thread in vote rejection rates.

“I remain dissatisfied,” Thernstrom replied. “We’ll slug this out later,” she said.

And so they did. In remarks after his testimony ended, Lichtman backed off the assertion that 54 percent of bad ballots came from blacks, warning that the figure should be “interpreted cautiously.” But he insisted that his conclusions were based on the “best available data.” Thernstrom, for her part, dismissed Lichtman’s protests that he was an impartial witness, asserting that he was on television “as a regular talking head for Gore” throughout the recount process.

Thernstrom didn’t wait to step outside the room to tangle with Berry, however. Berry asked early on that the commissioners “behave toward each other in a spirit of friendliness and collegiality. Do not personalize … your comments, because this is about policy, not about whether you like somebody or don’t like somebody.” But that didn’t keep Thernstrom from rolling her eyes at statements about racially disparate treatment in Florida, or repeatedly asserting that the report’s conclusions were “bewildering,” or that the three days the commissioners were given to review the findings were inadequate. When Thernstrom said that the commission had “compromised its integrity,” Berry cut her off, telling Thernstrom that “your feelings about the integrity of this commission” were irrelevant.

After the gavel sounded, Thernstrom accused the majority of the commissioners of partisanship, said that they had fatally compromised their moral authority, and said the report “could’ve been written by [Democratic National Committee Chair] Terry McAuliffe.”

Redenbaugh, who had been silent for most of the meeting, called the commission “intellectually bankrupt.” When asked what the solution was to the bias she saw in the commission, Thernstrom said she’d plant a bug in the president’s ear to clean house. “It’s definitely time for new ideas.”