Reps. Christopher Shays, R-Conn., and Marty Meehan, D-Mass., seemed quite recovered the day after Republican leaders in the House sent the duo’s campaign finance reform bill into legislative limbo with a parliamentary maneuver. In contrast to their weary, bitter performance in a post mortem press conference the previous night, the two relaxed in leather chairs in Shays’ office Friday morning, answering questions from a handful of reporters about the bill’s fate.

Shays was surprisingly calm, considering the slow-motion mugging that his bill received at the hands of Republican leaders. He said that he wasn’t surprised by the glee displayed by Majority Whip Tom DeLay, R-Texas, at the bill’s defeat, crediting DeLay with always stabbing from the front instead of the back. Shays also took the harsh words of Majority Leader Dick Armey, R-Texas, in stride, claiming that he still regarded Armey as a friend, despite the tirade he directed against Shays from the House floor on Thursday.

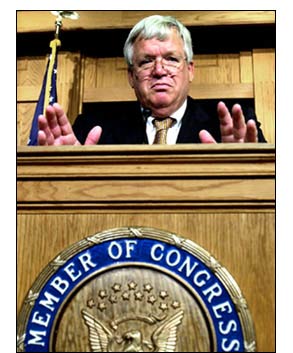

As for Speaker of the House Dennis Hastert, R-Ill., the man behind the sinking of Shays-Meehan on a procedural vote on Thursday, Shays had the kindest words of all for him. Shays said, “There’s no one I respect more than Denny Hastert.”

Whether a House speaker thrives on respect or fear, Hastert earned both as a Republican leader on Thursday with his maneuver on Shays-Meehan. He protected the president from what most of the party considered a poisonous choice between a veto and a fundraising nightmare, while playing the kind of hardball politics against Democrats and moderates that many conservatives had whispered he was incapable of. On Thursday, the New York Times attacked his villainy, deriding the procedural hardball he used to defeat Shays-Meehan as “thuggish.” Harsh words from the national paper of record, but a badge of honor for a conservative pol.

It was two short weeks ago that rumors were floating through Washington that Hastert might be quitting the House entirely. At the time, the speaker accepted the blame himself for fueling the speculation by making a careless remark in a television interview. Hastert had compared his political philosophy with the coaching philosophy he developed during his years teaching high school wrestling. The coaching experience, Hastert had asserted, taught him that it’s best to quit at the top of his game.

“Well, I’m not at the top of my game yet,” Hastert said, quashing the retirement rumor. With Thursday’s “success,” that might have changed.

While he’s earned high-fives from conservative colleagues for his handling of Shays-Meehan, there are still political risks associated with Hastert’s tactics. For one, by preempting an up or down vote on the bill, Hastert may have cheated Republicans of a greater victory. With the exception of reform hawk Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., none of the bill’s primary backers had expressed certainty on Thursday that they had enough votes to prevail. Efforts to steel the nerves of Republican reform backers and placate the concerns of Democrats in the Congressional Black Caucus had achieved only mixed results.

That means that the bill could’ve failed, with at least a handful of Democrats jumping their own party’s ship to kill the legislation, enough to call the bill’s defeat “bipartisan” with a semi-straight face. But the procedural measure was strictly the handiwork of Republicans, and so the GOP may have handed its opponents a freebie in the 2002 elections.

Another risk for Hastert is that his move radicalized reformers in both parties. That was evident in the new tough talk delivered by the normally low-key Shays during his Friday gab with reporters. While Shays refused to strike back for being called “small,” “arrogant,” “naive,” “embarrassing” and “unreasonable” by Armey during Thursday’s debate, he did promise to start fighting fire with fire on the floor.

After a period during which members on both sides of the issue can “take a nice deep breath or two and let cooler heads prevail,” Shays said, he was prepared to play hardball. “I’m going to be more active on my side of the aisle,” he said. “Those of us on the Republican side of the aisle will do anything and everything to ensure that we have a fair debate.”

That means that if Hastert and the GOP leadership continue to stall the bill’s progress, Shays says, he’ll tell anyone who’s listening about just how much money has poisoned politics, drawing from his own experience handling the fundraising demands of Republican Party bosses. While Shays resisted providing details on Friday, he hinted that continued leadership resistance to reform would leave him little choice.

“I am going to be very blunt about what we’re being asked to do,” he said. “I am going to make sure that when we walk over to the [Republican National Committee] to have a big meeting, and they give us a big stack of papers of people to call [for donations], you will have copies of those papers.”

And Shays said that he was willing to embarrass House leaders equally in the chamber and in the press. Citing the 19 Republicans who voted against their party on the Shays-Meehan debate as a potent force in a potentially multi-issue reform coalition, Shays suggested that those representatives and the Democrats could block debate on some other legislation, until GOP leaders gave reform a fair hearing. “This may be more distasteful, but it is certainly a possibility,” Shays said simply.

He might want to talk that strategy over a bit more with some of those rebel Republicans, because they seem less ready than Shays for an inter-GOP battle. Spokespeople for several congressional GOP members who voted with Democrats on the Shays-Meehan rule said that the representatives had no knowledge of a plan to block future votes.

A spokesman for Rep. Sherwood Boehlert, R-N.Y., said that all the backers of Shays-Meehan want a fair debate, but that Boehlert had not considered using vote blocks as a means to achieve that end. “He wants a straight up or down vote on Shays-Meehan,” said Boehlert spokesman Jim Philipps. “He would prefer not to play games.”

And Boehlert was not at all angry with Speaker Hastert over the bill, Philipps said. “He met with the speaker on this very issue, and he told him that on this issue, he would be voting against [Republican leaders],” said Philipps. “There wasn’t undo pressure.”

Likewise, Rep. Michael Castle, R-Del., who also voted down the rule, was satisfied with Hastert’s performance. “Mr. Castle has a very good working relationship with the speaker,” said Castle spokeswoman Elizabeth Brealey.

But the love-in might end for Hastert if Shays and other Republican reform backers go ahead with plans to pry Shays-Meehan loose from the Rules Committee with a discharge motion. Shays insisted that he preferred to aim for a quiet resolution to move the debate forward, one that didn’t humiliate Republican leaders, “so no one’s nose gets out of joint.”

At the same time, however, Shays seemed remarkably cavalier about the prospects of doing battle with party bigwigs. When asked whether he was afraid that his tough talk on campaign finance reform would provoke retaliation from the speaker or any other Republican leaders, Shays didn’t hesitate to respond.

“I don’t care,” he said. “I simply don’t care.”