Gary Groth read “Reinventing Comics” during the quiet dark hours when night turns into morning. The co-owner of esteemed comic book publisher Fantagraphics Books was in France, it was the summer of 2000 and his Riviera host Robert Crumb — creator of Zap Comix and other ’60s, psychedelic comic sensations — slept soundly in a room nearby. Art Spiegelman, author of “Maus,” the Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel about the Holocaust, also slumbered under the same roof without concern.

But Groth stayed awake. The veteran comics critic famous for publishing, among many other “underground” titles, both “Ghost World” and “Love & Rockets” could barely believe what he was reading. “Reinventing Comics” author Scott McCloud, who had built a reputation for intelligent comic analysis with 1993’s “Understanding Comics,” seemed to have swallowed gallons of Internet Kool-Aid. McCloud viewed the Net, much to Groth’s chagrin, as a savior. Arguing that “no art form has lived in a smaller box than comics for the last 100 years,” McCloud called for a revolution. If comics artists and fans would only embrace the digital world, he argued, the Internet would soon democratize comics, open up new artistic capabilities and even spark a resurgence of interest in the form. Like “an atom waiting to be split,” he wrote, the mix of comics and technology would prove powerfully explosive.

Groth figured otherwise. “He was terribly wrong,” Groth says, looking back. “It was dangerous agitprop. I took notes every night about where and why I thought he was misguided.”

Groth shared his grumbling with Spiegelman and Crumb, both of whom agreed that McCloud’s predictions amounted to little more than half-baked evangelism masquerading as insight. Then, in the March and May issues of the Comics Journal, Groth gathered his ideas and published a scathing two-part, 10,000-word review of “Reinventing Comics.”

First, he questioned McCloud’s economics, slamming him for ignoring the massive media conglomeration that threatened to keep audiences and dollars away from underground comics artists. Then he turned to aesthetics. Denying that the Net’s audiovisual capabilities would improve comics, he asserted that they would actually ruin the art form. Artists would inevitably turn comics into animation, undermining demand for serious works like “Maus” and creating an effects-dominated form not unlike contemporary film — “just another loathsome reality we’d have to tolerate.”

“At that point,” adds Spiegelman, in an interview from his New York studio, “you’re well on your way to a stage in the medium that was described by Marshall McLuhan — the time when a new medium cannibalizes the medium it came from.”

The arguments between Groth and McCloud sound a familiar chord to longtime Net watchers. On the one side, elitist defenders of a particular art form worry that the Internet will degrade and devalue the object of their adoration; on the other, passionate advocates are positive that the online revolution will spur an explosion of creativity. For every optimist like McCloud envisioning new chances for wide-open democracy there is a pessimist like Groth, sure that corporate dominance will prevail.

But the comics debate exhibits an intensity unmatched in other arenas. McCloud quickly published a strong rebuttal to Groth’s review, while Groth is considering another essay on the subject and just about every comics artist, online and offline, is more than ready to jump into the fray.

Some artists argue that the intensity derives from comics’ long historic relationship to paper. Without paper, how can there be true comics? Others believe that the debate is motivated by self-interest: Groth wants to protect Fantagraphics, while McCloud is seeking to establish himself as a “webcomic” visionary. Still others suggest that the comic book industry’s current dire straits are to blame. Faced with a dwindling comic book readership, distribution centered on hobby shops and the depressing news that market leader Marvel is still struggling to emerge from bankruptcy, comic artists and publishers are in a vulnerable state. The Net, like a tornado heading for a trailer, is bound to have some effect, good or bad.

“It’s like opera,” says Steve Conley, creator of Astounding Space Thrills, a daily adventure webcomic. “The fighting is so fierce because the stakes are so small. No other industry could have this kind of debate because no other industry is so small and close-knit.”

One thing is undeniable — love it or hate it, today’s webcomic scene is livelier than ever, full of energetic artists from all over the world. These artists are pushing the boundaries of the form, tackling complex, adult topics and attracting a diverse audience that rivals anything that may have existed during the heyday of the 1960s underground scene. Only a lucky few have figured out how to make any money on the Web, but for many artists, cash is less important than attention. Today’s comics artists, not unlike those of the ’60s, simply want to draw a crowd.

“Right now,” says comics artist Demian Vogler, “webcomics are a way to get famous, not rich.”

Vogler is a poster child for the new generation of webcomic artists. A lanky Swiss 24-year-old who laughs nervously when he isn’t sure what to say, Vogler embraced comics at an early age. He drew his first strips at age 12 and learned English, he says, “so I could read Superman.”

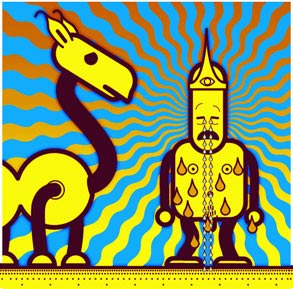

But Vogler never expected to actually develop a base of fans. He had worked on a story about a silly (and naked) Egyptian king who escapes his castle, unintentionally woos a camel and experiences numerous other (frequently bawdy) adventures. But he hadn’t gotten around to drawing the story while spending most of his time working as a graphic designer for commercials. His dreams of comics stardom, of finding an audience for his work, remained in the background.

Then, last summer, he read “Reinventing Comics.” Though he doubted McCloud’s business advice — a mass appeal for micropayments — he decided to put “When I Am King” online. Instead of splitting the story into panels, he created a series of horizontal scrolls — something only possible on the Internet. Employing exclusively digital tools, using an orange-centric palette and rendering characters that were somehow boxy but cute, the story moved according to mouse clicks on the right arrow.

Vogler added new episodes every week or two. And as his audience grew from 20 visitors per week to 10,000, he began experimenting with motion and space. He encouraged people to hold the right-scroll button down with arrows, making the screen move fast and giving the impression that the king was running. He even added animation: a dangling piece of genitalia here, a spinning flower there.

“I just happened to discover that you could animate some of the images, so I did,” Vogler says. “I didn’t use too much, though, because it would be distracting.”

One can almost imagine Groth’s hackles rising. To the old guard, animation is an insult to comics, transforming a real art form into low-class cartoons.

But McCloud, who was one of the first to discover Vogler’s work, disagrees. “When I Am King’s” use of limited animation done in loops, says McCloud, “somehow stays truer to comics. It doesn’t disrupt the flow. It represents a steady state.”

Vogler says that even though he may experiment with more movement, comics can still use limited animation and remain true to the soul of the traditional form. “There will always be a borderline between comics and animation,” he says. “There is a difference: In comics, it’s the space between images that defines time. And in animation, the time is determined not by the viewer but by the creator.”

The idea that comics artists want nothing more than to see their drawings move is simply “idiotic,” says Patrick Farley, creator of several innovative comics that can be found at e-sheep.com. “A comic is not simply a storyboard waiting to be turned into a cartoon,” he says. “It’s like saying a novel is simply a first draft of a screenplay.”

To artists like Farley and Volger, Groth and Spiegelman are ignoring the reality that today’s webcomic creators are still rooted in the classic conception of comics. At the same time, the Internet and digital media are creating new possibilities that they’d like to explore.

“It’s frustrating,” Farley says. “I feel sometimes like we’re 19th century geeks building a prototype automobile. We’re slowly pushing this cantankerous Model T down a horse trail, wheels spinning in the mud, engine groaning. At the same time, we’re trying to tell people galloping by on horseback that someday this thing will do an awesome 30 miles per hour. Obviously, when we’re stuck in the mud, we’re an easy target for jerks like Groth to unzip their pants and piss on us.”

Farley argues that Groth’s fears that webcomics will destroy classic comics are unfounded. Artists will be able to successfully strike their own balance.

Farley’s own work may act as a model. His “Apocamon” comic — a satirical take on the biblical apocalypse à la Pokémon — does employ animation, but only as a tool for dramatic emphasis. When God speaks to John, author of the book of Revelation, the words float from the background to the foreground; when heavenly hosts dance, the pink background moves horizontally. Otherwise, the comic remains static, a series of paneled pages that can be turned with a mouse click.

Other artists have also started toying with digital tools that aren’t available offline. Tristan Farnon’s “Leisuretown” offers a hilarious anatomy of a software start-up as told with photocollages and rubberized bunnies. On Mondays, Aric McKeown’s Professor Ashfield goes interactive, offering viewers three different captions for a single-image comic.

But most webcomic artists are experimenting less with form than with content — and taking advantage of the ease of publication on the Net to get away with whatever they want. Actual quality is rare — a comic book series like “Love & Rockets” has yet to see any serious online challengers from the new generation — but diversity is flourishing.

Some online comics play to obvious Internet strengths. Iliad’s “User Friendly” targets hacker culture, while “Player vs. Player” goes after the computer gaming crowd. But old standbys like sex and consumer culture are also favorite topics for the new generation of webcomic artists. “Exploitation Now” and “Jerkcity” mix pop-cultural criticism with dark, often sexual humor.

“College Roomies From Hell,” “Living in Greytown,” “Sinfest” and several others also offer regular sendups of everything from poetry slams to pop music. One strip of the comic “Diesel Sweeties,” which details a love affair between a woman and a robot, even took on another webcomic by dressing up a character as “Buzzboy” — an online comic superhero — whom no other character recognizes.

It would be overreaching to suggest that any of these comics approach the heft of Spiegelman’s “Maus” or Crumb’s classic “Self-Loathing” comics. In fact, many devolve all too often into penis-and-boob jokes, with plentiful cursing providing limited shock value. Groth and Spiegelman argue that the spread of webcomics threatens to undermine demand for lengthy, complex comic stories, but one also suspects that they simply don’t like what’s being published, and are looking for reasons to decry the entire phenomenon. There are no gatekeepers approving or disapproving the right of comics artists to publish online, a fact that may be a continuing affront to those who, like Groth, make their livings as critics and publishers.

Groth also dismisses the entire webcomic universe as a place that’s primarily filled with silly strips. He argues that this newspaper-mimicking format dominates because “the Net is all about short attention spans.”

“It takes three hours to read a serious comic book,” he says. “Most people want to read a comic in three minutes.”

And there’s a danger there, suggests Groth. Because the Net treats comics as “an inconsequential distraction,” he says, audiences are trained to see comics as nothing more than a simple way to waste time. It’s ultimately a matter of competition: The Net isn’t good for “serious form comics because it means there’s less room for them,” says Bill Griffith, “Zippy the Pinhead’s” creator and a friend of Groth’s. “With so many choices, many people will go on the Web instead of buying a Fantagraphics book.”

But is it true that webcomics and serious graphic novels can’t artistically coexist, or even merge? Some webcomic artists are already toying with longer forms, and succeeding. Maritza Campos, creator of “College Roomies From Hell,” recently ran a story line that lasted 22 weeks.

“My numbers never went down,” she says. “People will read what you give them, if it’s good enough.”

Chris Crosby, creator of “Superosity” and the founder of Keenspot, a webcomic co-op that hosts the work of about 50 artists, argues that webcomics are actually too complicated to encourage short attention spans.

“Many of our comics, some of our most popular ones, have such complex story lines and situations that you couldn’t even follow them if you had a short attention span,” he says. “If you wanted to start reading them, you have to spend four to eight hours reading the Web archive. That’s a giant commitment.”

“Webcomics are actually building the type of people who will be reading graphic novels and loving them in years to come,” says Crosby.

Even Spiegelman, who largely agrees with Groth’s pessimistic view of webcomics, maintains that “content isn’t the issue.” There’s no inherent reason why an Internet comic can’t be as good as “Maus,” he says.

But if content isn’t the problem, then what exactly is it about the Net that has Groth, Spiegelman, Griffith and others so up in arms?

The heart of McCloud’s thesis is that the Net is somehow better than outmoded paper — and that’s where the griping becomes most bitter. Young artists, comic book veterans argue, have grown overly enamored with the Web. They’re ignoring key proofs of the medium’s immaturity — its lack of business models that will sustain new artists and its low production values.

Even though e-mail makes it easier to keep up with a daily serial, “the physical book is still a lot quicker to access, of higher resolution and a lot more portable,” says Chris Staros, co-owner of Top Shelf Productions, an underground comic book publisher. And as musicians, filmmakers, authors and dot-commers have already discovered, the Web is no gold mine. The numbers rarely add up.

Webcomic artists don’t deny that Spiegelman and Groth have an economic point. Despite his best efforts, McCloud has converted only a handful of artists to the micropayment cause. The artists who do make a living from webcomics — such as Iliad of User Friendly — are rare.

But in today’s webcomic community, money is not the primary goal. In an industry where bestselling offline comic books sell only 100,000 copies, and where the overall audience for comics has dwindled to an estimated and paltry 500,000 people, few artists pretend that they’ll ever become wealthy through their craft. Instead, they care about reaching new eyeballs and moving comics out of the hobby-shop ghetto. Sure, the Web isn’t a perfect medium for comic delivery, but artists say they’ve embraced it because it offers what the comic book industry cannot: access to large, diverse audiences.

Indeed, for those like Vogler and Campos — who posts “College Roomies” from Mexico — the Net offers the only path of distribution that’s available. “Thousands of people from all around the world read every day my comic for a very low cost [to me], and it’s in full color, sometimes bigger than the average Sunday comic strip,” Campos says. “I couldn’t do that in print. In fact, if the Internet didn’t exist, I wouldn’t be a cartoonist, period.”

Even if Groth is correct, and today’s artists are placing too much faith in the Internet’s ability to revive the art and business of comics, the artists will continue to draw, to write and to post. Their mission is not to convince Groth through words, but rather through comics.

“There’s a simple way to shut the naysayers up once and for all,” say Farley of e-sheep.com. “Create amazing work and let that work speak for itself. That’s what [we’re] trying to do.”