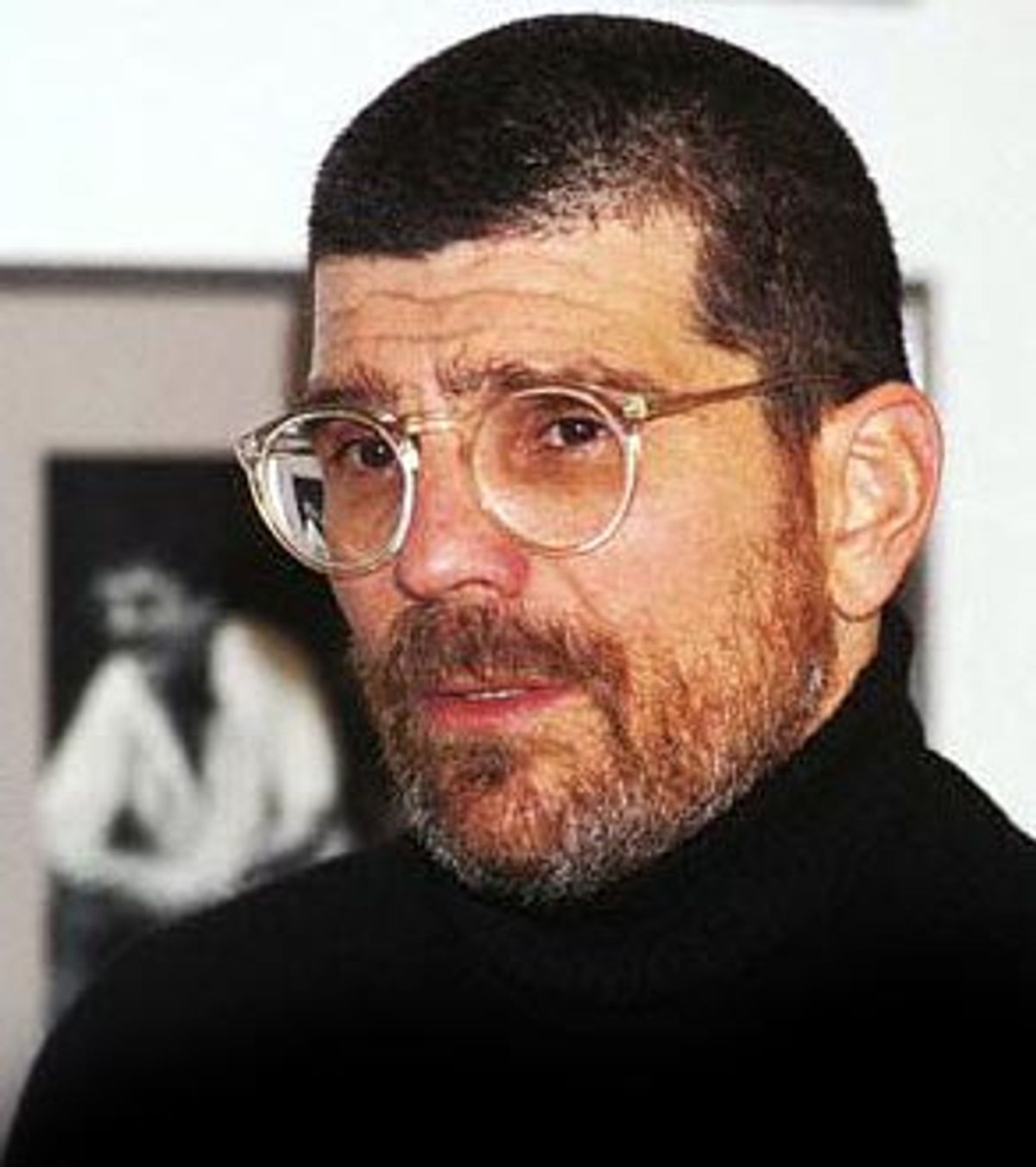

Playwright and screenwriter David Mamet knows what Joe Six-Pack likes, but he also knows how Joe Six-Pack lives and talks and what he needs, so much so that motivational experts actually use Mamet's film "Glengarry Glen Ross" -- which does for selling what skewers do for cherry tomatoes -- as a motivational tool. He once wrote porn, and maybe that explains how he mows down bullshit with his satire, yet still sells popcorn.

Mamet's machine-gun dialogue, both an "Airplane"-style joke on noir and a pitch-perfect copy of every overconfident asshole you ever met, is so beautiful yet utilitarian it's like holding a well-made steak knife when there's nothing to cook. You just admire it. His dialogue is so singular that it's called Mamet-speak, and when someone tries on the style, you know the clothes are borrowed.

Mamet's career began in the theater, where he moved from directing and acting to writing, crafting some of the finest plays of the late 20th century, including "Sexual Perversity in Chicago," "Speed the Plow" and "American Buffalo."

In the 1990s, he began writing tough, hard-driven screenplays like "The Postman Always Rings Twice," "The Verdict" and "The Untouchables," as well as fluffier work like "About Last Night ..." (the movie version of "Sexual Perversity in Chicago"), the Rob Lowe-Demi Moore Saturday afternoon TV staple that still possesses a crafty charm.

That split between the hard and soft can be seen throughout Mamet's screenwriting career. He's the kind of writer who gets the job done, whether he's working on diamonds or zirconia. "Our job, as writers," Mamet once explained in an interview with Matthew Roudane, "is to do our jobs. I was thinking the other day, I have trouble sometimes finishing a lot of plays. But then I always try to remind myself it took Sophocles 18 years to write 'Oedipus Rex'; that's also because he wasn't trying to write 'Gigi.'"

Mamet needn't worry too much about output, since, besides the screenplays and scripts, he's produced novels, essay collections, articles and even books for children. He's a little like the baseball player who effectively plays every position on the team; his credits are as diverse as they come, ranging from "Hannibal" (writing) to "The Spanish Prisoner" (directing and writing), "We're No Angels" (writing) to "House of Games" (writing and directing). This versatility is explained by Mamet's belief that movies should entertain first. Shorn of mass audience concerns, he sinks even deeper into the audience, right into their subconscious, never succumbing to the kind of overindulgence that often mars "independent" films.

Born in Flossmoor, Ill., on Nov. 30, 1947, Mamet found only fresh turmoil when he left his mother and stepfather to try life with father. His sister and fellow writer Lynn Mamet once explained life with the tough-to-please parents: "Suffice it to say we are not the victims of a happy childhood. There was a lot of violence, but the greatest violence was emotional. It was emotional terrorism."

That emotional terrorism seemingly found its way into Mamet's grifting and scamming characters. They're always trying to trick and trade their way to success, respect or, at the very least, some crumb -- even if won by deceit -- of self-respect. In Mamet's best work, the American economy itself is a parent whose admiration can't be won, except by chicanery.

Take the film version of Mamet's "Glengarry Glen Ross." A group of sales schmucks, down-and-outers who've outgrown the confidence of everyone but themselves, barely, face the wrath of Alec Baldwin, a top-down guy sent by company honchos to shake out all but the first- and second-place winners in a selling contest.

"First prize is a Cadillac Eldorado," Baldwin explains. "Anybody want to see second prize? Second prize is a set of steak knives. Third prize is you're fired." He then delivers coach-speak, summarizing all the crap jobs in America, reminding his men that they're losers for not trying hard enough, or, more to the point, not being man enough.

In protest, a muttering Jack Lemmon heads for the coffee machine. "Put that coffee down," Baldwin demands. "Coffee's for closers only."

"What's your name?" another salesman asks.

"Fuck you! That's my name. You know why, mister? 'Cause you drove a Hyundai to get here tonight. I drove an $80,000 BMW. That's my name ... You see this watch? That watch cost more than your car. I made $970,000 last year. How much you make? You see, pal, that's who I am and you're nothing. Nice guy, I don't give a shit. Good father? Fuck you. Go home and play with your kids."

It's what it means to be demeaned for a living, to open up and swallow the ridicule of a jerk, because you've got no choice and the jerk knows it. "Only one thing counts in this life," Baldwin instructs. "Get them to sign on the line which is dotted."

"Glengarry" alone would justify a career. By the end, you see how far men will go to survive, not just financially, but as men. They fail and they know it, and they're thrashing and grabbing and lying to themselves about it. Baldwin's character talks to his men the way he does because he can. "It takes brass balls to sell real estate. Go and do likewise, gents. The money's out there. You pick it up, it's yours. You don't, I got no sympathy for you. You want to go out on those sits tonight and close? Close, it's yours. If not, you're gonna be shinin' my shoes."

There's a trademark rhythm to Mamet talk. It's like the patterns you find in Steve Reich's minimalist music, a lapping of the shore on the coast. It comes, it goes, it comes back again. Sometimes it hits soft, sometimes hard, but it's coming, coming. It's looping, repeating, sometimes enervating. It sticks in your head like pop music. It's short, tough, buried and revealing at the same time, like a friend at the gym, coming apart at the seams during a bench press. One of the men, considering a plan to rip off the cherished sales leads, asks: "Are you just talkin' about this or were you just talkin' about it?" Mamet's characters repeat things, trying to nail down a slippery reality, their phrases fingers grabbing onto a ledge.

And range? "The Winslow Boy" is a low-key, low-profanity drama with enough British accents it could have aired on PBS, except it's not boring. One young boy, and what he did or didn't do, sucks us into a world that reminds us how vicious childhood can be, and how forgiving and unforgiving the adults who took care of us can be.

Or take "State and Main," the best cherry tomato-popping Hollywood skewer since "The Player." A film crew comes to a small town and does what film crews do -- trashes it. As a movie construction coordinator once told me, it would be much quicker and less painful to burn his own house down than let a bunch of production assistants loose in his living room.

There's the ongoing gag in "State and Main" regarding Sarah Jessica Parker's showy refusal to show her breasts on camera (a joke her "Sex and the City" co-workers must relish). And there are a whole bunch of sincere folk in town who all know they're made for fame, just as every American must prove Andy Warhol was right about something. It sounds like trite satire, a subject not worth the bother, until you see it and begin to like the people parodied, and you see that Mamet seeks not to ridicule his characters, but to get at something essentially heartbreaking about them.

Even one of his weaker efforts, "Wag the Dog," practically predicted and then named a political event we unfortunately won't forget for a long time. Maybe it would have been funnier had it not merged with events that satirized themselves, rendering ridicule superfluous.

Some say Mamet's second wife, actress Rebecca Pidgeon, has had a profound influence on his work, as has his own deepening commitment to Judaism. Like all real satirists, his best work stems from heartbreak, or at least heartache. He nails the essential meanness of America. It's the linebacker taking out the quarterback because that's what it takes to win. It's funny because it's so painfully true, and it would be even funnier if it weren't. Mamet's belly-laugh dialogue comes at a price: You laugh so much it hurts.

Shares