That furry cup, when first exhibited in New York in 1936, caused an absolute sensation. Of all the surrealist art on show, this was the one that got the town talking. Well, it was a good one: funny, poetic and deeply transgressional all at the same time. It hit the spot.

After all, Meret Oppenheim’s “Object,” a cup, saucer and spoon covered in gazelle fur, is so surprising that its perversity is undermined by its brilliantly playful quality. And it’s still funny. But is it still poetic and is it still a transgression? In the U.K. there is a television comedian called Ali G who, confounding correctness, has made it his trademark to ask serious-minded lesbians if it is “good to drink from the furry cup.” Surrealism has long since found its way into the music-hall joke.

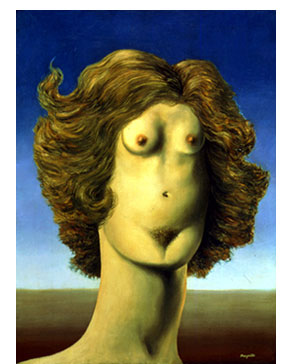

The poetry and transgression that was so much of surrealism’s anarchic force has been recruited into mainstream culture. It has been made commonplace by television and magazine merchandising, by computer games and Internet visuals, by film and MTV, by the fashion shoot. Every day the eye is subject to a thousand tiny shocks as a thousand industries compete for the eye-kick, the visual hook that will lock the consumer into product for that crucial second where the tiny — or not so tiny — leap of the imagination is made. And what does it better than sex? We’ve been educated out of the shock of surrealism, and as for the sexual frisson so central to this art movement, it sometimes seems that there isn’t a lot left to surface. Unless it runs to the very dark.

Which brings us to “Desire Unbound.” It is a wonderful, bulging compendium and, as the title suggests, the focus is on the sexual response. The surrealists saw desire as the hidden voice, the key to the true nature of the inner self. This brilliantly curated exhibition now open at London’s Tate Modern through December (and traveling to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York Feb. 6 to May 12, 2002) offers a kind of essay on the unfolding nature of the artists’ preoccupations with desire.

But in that there is a problem. A series of chambers, differently mooded with subtle lighting, suggest different states so that the visitor walks through a mentalistic universe. The entrance contains a spectacular hanging of that great icon of the movement, “Men Shall Know Nothing of This” by Max Ernst. The work is suspended uniquely in a black light chamber, the visitor kept at a distance, peering in, while a heartbeat throbs violently. It promises the excitement of a dream to follow, but it doesn’t quite deliver. Each chamber carries an enticing label such as “The Bride Stripped Bare,” “The Accommodations of Desire and Her Throat Cut,” and the exhibits are conceptually grouped. But sometimes it’s a bit of a stretch to go with the concept.

It’s a rationalization of swinging emotional states: clever stuff, but strangely at odds with the search for the unconscious impulses and weird poetic crossovers that surrealism is all about. Maybe the designers of the exhibition were straining a little too hard here, not entirely trusting the art to do its job. In some ways the exhibition is more rewarding if you forget about the conceptual grouping and wander the moody halls making your own connections. The overintellectualization of surrealism can be a bromide. A dream interpreted is a deflated dream.

The designers have worked hard on trying to create a distortion. In the chamber called “Before the Mirror” there are two translucent mirror doorways. Curator Jennifer Mundy describes their function. “People will come in and out of focus in the mirrors because of the way the light is arranged, and that’s a metaphor for desire: You want to see but you can’t see. Desire involves not getting what you want as much as achieving the object of your desire. This is an example of the ways we have tried to address the irrational.”

Through the distortions one can find clarity of purpose. It’s great to see in this comprehensive assembly work absolutely seminal to the surrealists, like Giorgio de Chirico’s mysterious painting “The Child’s Brain.” The story goes that Andre Breton saw this painting in a gallery window from a bus. So struck was he that he got off the bus to go and inspect it, and later bought it, displaying it prominently in his apartment for most of his life. It certainly is a painting that exudes a sense of repressed sexuality and withheld paternal love, and gloriously admits to so many interpretations that it defies reduction. The exhibition is crowded with gems.

There are many of surrealism’s greatest hits here, along with a lot more obscure material, and a considerable collection of pamphlets, publications, poetry and photographs connected with the movement. There is a copy of Robert Desnos’ booklet “La Liberte ou L’amour,” published in 1927 and, of course, censored. It stands open at his discourse on the Sperm Drinker’s Club. A translation from the French reads: “The Sperm Drinker’s Club is a vast organisation. Women are paid by it to masturbate the handsomest men throughout the world. A special brigade is dedicated to the quest for the female liqueur … Each harvest is stored in a small phial made of crystal, glass or silver, meticulously labelled and despatched with the utmost care to Paris. The founders of the club, top occultists, met for the first time at the beginning of the Restoration (1815). And since then passed down from father to son the society has continued with the dual aegis of love and liberty.”

There they go again, those top occultists.

Salvador Dali is well represented here — perhaps overly represented because the Tate owns so many of his famous works. Some of the pieces have been shoehorned into the concept, and he is one of the surrealists I least associate with Eros in the forces he conjures. For example, his “The Accommodations of Desires,” from which one of the conceptual chambers takes its title, seems, like much of his work, to be figured around neurosis, disgust and emotions of anti-desire. But Matisse, Man Ray and Delvaux and all the usual suspects are gathered for the party, photographed in full brigade turnout, with and without the husbands and wives they seemed to share in pursuit of the primal force generating surrealist art. You can even play the game of detecting “who went insane after sleeping with whom” in the hope of tracking down the original spirochete of madness if that sort of thing interests you.

The exhibition breaks exciting ground in the final two chambers, particularly with the work of some of the later and rather less-feted women practitioners. Surrealism was fond of casting women as muse creatures, as enigmatic child-women or alluring bird figures. Yet from the mid 1930s a new generation of women artists were attracted to the movement, and the self-representations move from the sexually passive to the active, to shamanistic and transformative, event threatening forms.

Dorothea Tanning’s “Birthday” is a self-portrait in which she appears bare-breasted, almost Amazonian, a scary enchantress with a skirt of swirling naked torsos and a demonic familiar spirit at her feet. Leonora Carrington’s “Cat Woman” sexualizes ancient Egyptian statuary. Eileen Agar’s blindfolded head “Angel of Anarchy” evokes a similar spooky power, as does work by Toyen and Frida Kahlo. It is clear that these women artists were working with very different elements, emotionally. (In fact Kahlo was contemptuous of the male-dominated movement.) Certainly the formulas for depicting desire are darker, and somehow more visceral.

Jennifer Mundy talks of “a sense of imminence” of this period, in which something new entered the movement. “From the 1940s,” she says, “the movement was very much connected to ideas of magic. Though many of the surrealists were uncomfortable with this turn as they felt it offered no answer to questions of Stalinism, of communism, of the atomic bomb. Though Breton himself said in 1944 that it was time to value women’s ideas over those of men, which he described as bankrupt.”

These works command a shudder of recognition that has somehow deserted many of the other, more famous, pieces, which are perhaps worn out by familiarity. Jennifer Mundy gently disagrees. “Even those who know the images well through reproductions will be drawn by the tactile, physical qualities of the exhibits. And the themed nature of the exhibition will itself have disruptive qualities.”

She goes further. “The aim of surrealism was never to be provocative for the sake of provocation only. It was to disrupt people’s way of thinking about the world and I think that challenge still poses questions for us today.”

The key to understanding the surrealists, and this exhibition, lies in the way that the surrealists saw desire as being the thing that made the imagination tick. Perhaps this is why there is a relationship between eroticism and the act of thinking itself. The imagination is not unchained at all: It is chained by desire.

The air of the visitors to the Tate while I was there was oddly muted, casual even. I did not detect the frisson, the sense of transgression one might associate with an exhibition like this. Certainly the surrealists cannot be viewed as thoroughly modern. Their preoccupations might even be said to be romantically heterosexual in character and do not confront darker matters of desire surfaced over the course of the last century — such as rape, prostitution and pedophilia.

Perhaps it is no longer possible to witness a public expression of sudden insight into the dark movements of desire in the human psyche. When a barrage of aggressive modern media has made public so much sexual content it is perhaps not surprising. Even the merchandising in the hall outside the exhibition offers a Dali Lobster Telephone Book and a surreal PVC shopping bag. Repression in the human psyche is tightly bundled. When it has been pulled out of the sprung package so often it is perhaps difficult to push it back in the box.

After all, the furry cup is on permanent exhibition in New York.

Nevertheless, this exhibition is unmissable. The sense of a movement sideways since the inception of the surrealist movement is unmissable, too: Still we strain at the bonds.