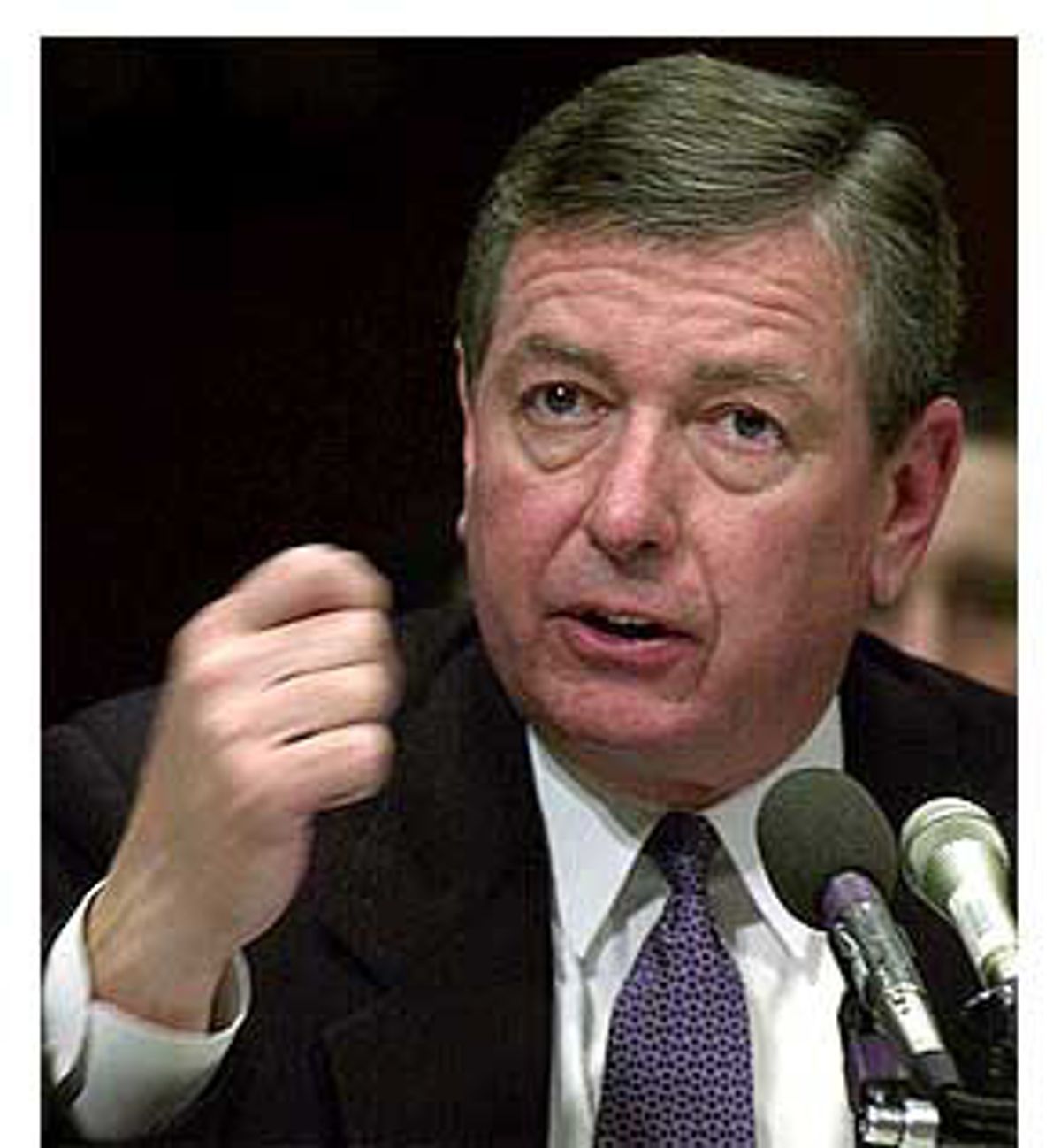

The hearing wasn't even close to over when Sen. Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., proclaimed Attorney General John Ashcroft the winner of his Thursday face-off with the skeptics of the Senate Judiciary Committee.

Eighty-seven days after the most horrific act of terrorism in U.S. history, Ashcroft came before the committee to answer questions about civil liberties and President Bush's order for a military tribunal for non-U.S. citizens involved in terrorism. But for a chunk of the hearing the Democrats on the committee barely asked him about such matters, McConnell noted. Instead they peppered him with questions about the Justice Department's refusal to let the FBI use a law enforcement firearms database -- the National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS) -- to see if any of the 1,200 or so individuals detained in the post-9/11 dragnet had ever purchased a gun.

"The best evidence that you've won the public discussion on the tribunal is that this hearing has changed into a discussion about gun control," McConnell gloated.

That Ashcroft "won" the debate still seems a fairly premature call, especially since so many questions about the tribunal -- which Bush slipped into the Federal Register on Friday, Nov. 16 -- remained vague. Like who, exactly, could be tried. Or what the burden of proof would be. Or whether it would be a court only for war crimes or one for "violations of the laws of war and other applicable laws," as the order states. Or whether the death penalty could be applied if a defendant was convicted by a 2-1 vote. Or whether the president or Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld could overrule an acquittal and single-handedly send a defendant to his death. Trifling little matters like that.

But the fact that throughout the hearing Ashcroft refused to bend when confronted with probing -- often disapproving -- questions is indisputable. So if determined elusiveness was McConnell's yardstick, Ashcroft did indeed take home the gold. Ashcroft kept inquiries about basic details of the tribunal unanswered, insisted that Bush had no need for any congressional sign-off on the controversial measure, and even challenged the patriotism of those who questioned the measures the administration was taking to prevent future terrorism attacks. And though Democrats on the committee -- along with Sen. Arlen Specter, R-Pa. -- were clearly displeased, there seemed little that they were willing to do about it, even (or is that especially?) in the face of Ashcroft's searing rhetoric.

"To those who scare peace-loving people with phantoms of lost liberty, my message is this: Your tactics only aid terrorists, for they erode our national unity and diminish our resolve," Ashcroft said in his opening remarks. "They give ammunition to America's enemies and pause to America's friends. They encourage people of good will to remain silent in the face of evil."

Following complaints that he only spent an hour before the committee on Sept. 25 after requesting sweeping counter-terrorism legislation, Ashcroft came loaded for bear Thursday morning at 10 a.m. -- "unsenatorial in arriving early," he privately joked to committee chairman Sen. Pat Leahy, D-Vt. Ashcroft had clearly had his Wheaties, holding his ground throughout the three and a half hours' worth of doubts and misgivings about the administration's attitude toward civil liberties. "The need for congressional oversight and vigilance is not, as some mistakenly describe it, 'to protect terrorists,'" Leahy said. "It is to protect ourselves and our freedoms."

But in the security vs. civil liberties debate, security was clearly still the easier principle to defend, especially in light of public opinion polls indicating that the American people are willing to give up a lot as long as most of the real infringements don't happen to anyone they know. "We are at war with an enemy who abuses individual rights as it abuses jet airliners -- as weapons with which to kill Americans," Ashcroft countered. Thus, Ashcroft argued, post-9/11 law enforcement measures were no more objectionable than various airplane security measures. He has "one single overarching objective," he intoned. "To save innocent lives from further acts of terrorism."

Those with conflicting concerns did not share, therefore, his one single overarching concern. Those who thought Sept. 11 was "a fluke," who think we need "to do nothing differently," are "liv[ing] in a dream world," Ashcroft said -- at a moment, coincidentally, when Sen. Herb Kohl, D-Wis., appeared to be napping.

The whiff of mortality permeated the room -- and not just because of a sad cameo by feeble former Dixiecrat Sen. Strom Thurmond, R-S.C., 99 years young on Wednesday. The hearing was held in the Dirksen Senate Office Building, Leahy pointed out, because the Hart Building was still closed due to anthrax contamination. But that didn't stop Ashcroft, who made his case for the suspension of some civil liberties, from further scaring the bejesus out of the room.

"My day begins with a review of the threats to Americans and American interests that were received in the previous 24 hours," he said. "If ever there were proof of the existence of evil in the world, it is in the pages of these reports. They are a chilling daily chronicle of hatred of America by fanatics who seek to extinguish freedom, enslave women, corrupt education and to kill Americans wherever and whenever they can."

Many of these fanatics are still in our communities, he said, "plotting, planning and waiting to kill again. They enjoy the benefits of our free society even as they commit themselves to our destruction. They exploit our openness -- not randomly or haphazardly -- but by deliberate, premeditated design."

Some senators had complained that the executive branch wasn't adequately working with the legislative branch. "There's been no consultation," Leahy complained to the New York Times. "These things just get announced: 'George Washington got a British spy once by doing this, so thank goodness we've got recent precedents.'"

But on this, Ashcroft didn't budge. "In some areas, I cannot and will not consult you," he said, beginning a Dr. Seussian cadence. He "cannot and will not divulge the contents, the context, or even the existence of advice" he gives to the president, and "cannot and will not divulge information ... that will damage the national security of the United States."

On this he was clear. On this and pretty much everything else he was backed by most of the committee Republicans, almost all of whom prefaced their remarks with plaudits for the magnificent job their former colleague was doing. In a thinly veiled barb aimed at Leahy, Sen. Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, the committee's ranking Republican, said "we could all check our egos ... Do any of the members of this committee really believe that in this time of crisis the American people -- those who live outside the Capital Beltway -- really care whether the president, the secretary of state, or the attorney general took the time to pick up the telephone and call us prior to implementing these emergency procedures?"

Ashcroft provided the committee with 100 pages excerpted and translated from an al-Qaida training manual used as evidence in the trial of the 1998 embassy bombers. "In this manual, al-Qaida terrorists are told how to use America's freedom as a weapon against us," Ashcroft said. They use our free press and our fair judicial process, he said.

In an apparent attempt to quell anecdotal complaints from human-rights groups about prisoner mistreatment, Ashcroft revealed that in the manual "imprisoned terrorists are instructed to concoct stories of torture and mistreatment at the hands of our officials." In an apparent defense of his recent decision to monitor the lawyer-client phone conversations of a select list of suspected terrorists, Ashcroft noted that in the manual, "they are directed to take advantage of any contact with the outside world to 'communicate with brothers outside prison and exchange information that may be helpful to them in their work.'"

Right now, 16 prisoners out of a total of 158,000 in the federal prison system are subject to such monitoring, the attorney general said. "It's very few," Sen. Jeff Sessions, R-Ala., said supportively.

Hatch bemoaned the "extreme interpreters" of the Constitution who want to grant extensive rights "to criminals, even terrorists!" Hatch quoted from a recent press release by Sen. Zell Miller, D-Ga., who Wednesday said that Judiciary Committee Democrats "need to get off his back and let Attorney General Ashcroft do his job. Military tribunals have been used throughout history. The Supreme Court has twice upheld them as constitutional. These nitpickers need to find another nit to pick."

But pick the nits the nitpickers did. Specter wondered about one detainee whom two judges had allowed released -- whose release was later overruled by Ashcroft. The cantankerous Pennsylvania Republican also wondered why, if the Department of Defense was handling the decisions about the tribunal, Bush's declaration was written on Justice Department stationery. Sen. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., pointed out that the tribunal order seemed to allow prosecution not just for war crimes but "other applicable laws." Russ Feingold also probed at holes in Ashcroft's justifications for not releasing the names of the 600-plus detainees. Ashcroft had said that releasing the names would help Osama bin Laden and al-Qaida. But some time after that, Feingold pointed out, Ashcroft said that the detainees were not being prevented from going to the media themselves. It would seem that if releasing the names of the detainees would help al-Qaida, Ashcroft would prevent the detainees from releasing their own names as well, Feingold said.

"This is not a game of gotcha," Leahy said at one point, rather unconvincingly.

Ashcroft took all the questions, handling them coolly, swatting them away like so many gnats, or nits. He said he overruled the two judges in the name of national security. He dodged the DOJ stationery inquiry. He said that the intention was just to try war crimes, nothing else. And he brushed aside Feingold's arguments with a sort of bemusement. He said repeatedly that since the Department of Defense was still drafting the tribunal rules, "the answers to some of these questions would be premature."

Substance aside, Ashcroft did seem to win the match.

The nation seems to want a stern, serious man as A.G. right now and Ashcroft -- with a 76 percent approval rating, according to a recent Ipsos-Reid Express poll -- appears to be filling that role. The public overwhelmingly supports his counter-terrorism measures, which the media label "controversial." A recent Newsweek poll indicates that 78 percent of the public supports indefinitely detaining legal immigrants suspected of crimes as a way to protect against terrorism.

So while the Democrats had much to complain about regarding Ashcroft's recent moves, few laid a glove on him. During a break in the hearing, civil rights hustler Al Sharpton said to Sen. Ted Kennedy, D-Mass., "You're the only one who asked a tough question all morning."

During that break, Feingold expressed disappointment in Ashcroft's remark that his critics were "aid(ing) terrorists."

"He knows better," Feingold said. The Madison liberal -- the only member of the Senate to vote against the counter-terrorism bill -- groused that Ashcroft wasn't giving "straight answers about the tribunals. The runaround continues."

Back at the hearing, Feingold asked Ashcroft to clarify whether he was referring to the Judiciary Committee when he talked about people aiding terrorists by asking questions of the administration. Ashcroft insisted that he had been referring to "news organizations" that had reported unfairly and inaccurately about the administration's efforts. His announcement that the special law enforcement "taint team" would monitor some lawyer-client phone calls was portrayed as "eavesdropping" in the press, which he described as "a gross misrepresentation." Prisoners would be informed ahead of time that their calls could be monitored. Thus, he argued, the listening wasn't being done secretly, and thus it wasn't eavesdropping.

For Republicans and journalists, the best moment of the hearing probably came when Ashcroft contemplated the alternative to a military tribunal. Once the U.S. tracks down those responsible for the Sept. 11 attacks, Ashcroft asked, "Are we supposed to read them the Miranda rights, hire a flamboyant defense lawyer, bring them back to the United States to create a new cable network of Osama TV?"

For critics, perhaps the highlight of the hearing came when trial lawyer Sen. John Edwards, D-N.C. -- seemingly a John Grisham protagonist come to life -- pointed out a number of loopholes in the president's military order that created some troubling potential scenarios. While Ashcroft insisted throughout the hearing that any tribunal defendant would have a "full and fair" trial, Edwards pointed out that the tribunal rules appear to allow unlimited detention -- which Ashcroft said was not the intent.

Edwards went on to point out that the order would allow Bush or Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld to overturn an acquittal vote and sentence someone to death. The death penalty also seemed to be applicable even when a defendant's guilt was determined by a 2-1 majority vote. Ashcroft said that defendants were found guilty by majority vote in other international war tribunals in, say, The Hague -- though Edwards noted that those tribunals don't mete out the death penalty.

Asked to explain his personal opinion as to what the burden of proof should be, especially for a capital case -- whether "beyond a reasonable doubt" or "greater weight of the evidence" or "preponderance of the evidence" or "51 percent" -- Ashcroft demurred. Asked about the lack of an appeals process for convicted tribunal defendants, Ashcroft said that either Rumsfeld's or Bush's good graces could be appealed to. "The president and the secretary of defense are the ones who decide the prosecutions in the first place!" Edwards noted.

Other senators tried in vain to stump for their own various anti-terrorism bills. Leahy wants to draft the military tribunal from legislation rather than executive order. Feinstein wants to institute criminal background checks at gun shows, where terrorists from both Hezbollah and the Irish Republican Army have been able to secure arms. Ashcroft remained noncommittal.

When Sen. Maria Cantwell, D-Wash., asked for Ashcroft to commit to giving the Senate four or so Justice Department briefings a year to ensure that Internet-probing technologies like Carnivore and Magic Lantern were being utilized properly, Ashcroft responded as innocuously as if he were concluding a draft letter to a crank constituent. "I welcome the opportunity to work with you toward those objectives," he said.

Sen. Charles Schumer, D-N.Y., among others, tried repeatedly to ask Ashcroft why, if he thought the FBI was not legally allowed to use the Department of Justice database to determine whether one of the 1,200 detainees had purchased a gun, he didn't seek to add that power when he was drafting the counter-terrorism bill. So many other constitutional amendments were being infringed a bit in the name of safety, what was so sacrosanct about the Second? Schumer could have a bill drafted by the end of the day that would solve the NICS problem -- would Ashcroft want that?

"I don't want to make a commitment to any legislation without having seen it," Ashcroft said.

"When it comes to illegal immigrants getting guns, this administration becomes as weak as a wet noodle," Schumer remarked.

But Ashcroft turned the Democrats' argument around, jujitsu style, saying that they seemed to want him "to respect some rights and not other rights."

He had the confidence of a man who knows that he can egregiously pander to the gun lobby because his nation is firmly behind him. Lefties and civil-liberty types argue that when those polled are given more details about Ashcroft's proposals and actions, support begins to erode. But most Americans don't know the details, and they don't care to know them. They just want to be safe.

So Leahy & Co. have a problem: When Ashcroft says, as he did Thursday, that "thanks to the vigilance of law enforcement ... we have not suffered another major terrorist attack," they have no facts with which to rebut him. (Ashcroft doesn't necessarily have any facts, either, but if he did he couldn't tell us anyway. National security, you understand.)

Tick tock. By 1:45 p.m. every senator had gotten his or her turn at the mic and the game was called. The Democrats had made their displeasure apparent, but Ashcroft didn't seem to care. Hatch tried a neat trick, reading a pro-tribunal statement by Francis Biddle, attorney general for Franklin Roosevelt, substituting "al-Qaida" for "Nazis" and "terrorists" for "saboteurs."

"History shows the driving force behind" those tribunals, Leahy countered, "was to cover up the mistakes of J. Edgar Hoover. Two saboteurs had to beg the FBI to arrest them!"

Ashcroft smiled politely and left the room, Leahy's opinion about Hoover notwithstanding.

Shares