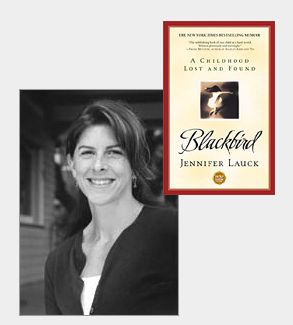

Pain is no stranger to either Jennifer Lauck or Jonathan Lantry. Lauck, a 38-year-old writer and mother, is the author of two memoirs, “Blackbird” and the recently published “Still Waters,” which when combined chronicle a miserable childhood made even worse by the almost classically wicked stepmother she calls “Deb.” Lantry, a 39-year-old carpenter, is Lauck’s stepbrother, son of “Deb,” and shared that terrible childhood with Lauck for three years. Lauck’s pain — specifically in the form of “Blackbird” — was blurbed by Frank McCourt, validated by Oprah and Rosie O’Donnell and reviewed by national glossy magazines. It can be read in 15 languages. “Blackbird” was on the New York Times Bestseller List for three weeks, and has sold some 100,000 copies in the United States. Recently it was nominated for the Oregon Book Awards nonfiction book of the year.

“Blackbird” has its Dickensian elements. Adopted by Janet and Joseph “Bud” Lauck, Jennifer was 7 when her mother died. Her family then went from living a middle-class life in Huntington Beach, Calif., to a disjointed existence in Downtown Los Angeles. Her father married “Deb,” a member of the “Freedom Community” church, a pseudonym Lauck uses for what was in actuality the Church of Scientology, and then had a fatal heart attack. At age 10, Lauck and her brother, Bryan, were orphans and left in the care of their cold, authoritarian stepmother who attempted to break the little girl’s will. Lauck writes of being mistreated by “Deb,” sexually molested by a counselor at a church-run summer camp and, finally, abandoned by the awful stepmother, sent at age 10 to live by herself in one of the church’s group homes and to earn her keep by working as a janitor’s assistant at a local school. Years later her brother committed suicide.

The Denver Post called “Blackbird” “heart-wrenching, vividly remembered, and shockingly real.”

Lantry thinks not. “She’s lying her freakin’ head off,” he said from his home in Napa, Calif. And he’s not alone in thinking so.

In that spirit, Lantry is attempting to marshal enough testimony and hard evidence to prove Lauck’s nonfiction so full of holes that it must be reclassified as fiction either by the publisher, Pocket Books, or by the New York Times. Willamette Week, a local Oregon newspaper, first brought his claims to light on Oct. 17. Since then, Lantry has enlisted his mother, other family members and family friends from the time period covered by “Blackbird” in his campaign to debunk Lauck’s memoir.

Lantry says there are more than 100 eyebrow-raisers in “Blackbird.” “She ties together all of her untruths with basic truths,” he says. Some of those inaccuracies seem minor enough to be the result of honest misremembering: the cost of a dog, the color of a car, how many hours a day were spent in a swimming pool, the view from a home. Lantry maintains that Lauck has in numerous instances messed around with timelines and gotten ages and dates wrong. Lauck, Lantry points out, even gets her own father’s middle name wrong; it is Everett, not Edward. (A copy of Mr. Lauck’s death certificate confirms this.)

In one scene that has particularly touched readers, Lauck describes being told by “Deb” that she would have to move the beloved bedroom set given to her by her father to her new room in the group home all by herself. Lauck relates her grueling and piteous labors in moving the furniture, piece by piece, over a distance of 11 city blocks. Lantry insists that the distance was not 11 blocks but a mere 100 yards.

Lantry’s greatest concern, however, is for his mother, the memoir’s supremely hateable “Deb.” Lauck appeared on “Oprah” with two other adults at the end of October 2000 in a segment entitled “I Was an Abandoned Child.” The claim is patently false, Lantry said.

“Deb” herself has mixed feelings. Now 65, she asked that Salon refer to her as “Eva,” a name she once used. When asked to respond to her stepdaughter’s account of their years together, her tone swings from measured to menacing and back again. In an e-mail she wrote, “Twenty people can see an accident and they each see something different. There are differences in memories from person to person, as is natural. They were children. I was an adult.”

Interviewed by telephone from her California home, Eva added that Jennifer “probably felt emotionally abandoned because her father was dead, and we were in this Scientology commune. There was a sense of group but not family.” (From “Blackbird,” readers might get the sense that Jennifer’s father joined the church after becoming involved with “Deb.” According to Eva, Bud was already caught up in the church when they met.)

But in another e-mail, Eva wrote of Lauck that although she did not want “to do her in … I want a sort of mental taser [sic] or aqueous foam to immobilize the bitch, hoping to sober her up and make her think twice before going after other people with her dolorous tales of misery. Sort of like President Bush telling the Taliban that if they don’t stop we would begin bombing. I really don’t wish her harm.”

Eva said she has not read “Blackbird.” She said her son and youngest daughter (who “blew her top” after reading it) told her what it said. “I felt, oh, shit, she’s done it,” Eva said. “Finally, she’s got me. I told her [as a child that she] would not get away with lying to me, and then I find out about the book. People do believe her … It doesn’t really surprise me because the Jennifer I knew would do that, tell that kind of story.”

The “kind of story” Lauck would tell, for example, is one in which the beloved bedroom set was chosen for her by her father. Not so, according to Eva. “My eldest daughter had a canopy bed with white eyelet covers and Jennifer really loved it,” Eva stated via e-mail. “She only had the Hollywood bed, so for her birthday, December 1972, I looked in the Sears catalog and ordered a white canopy bed with dressers and chests as well as covers and curtains made in three tiers of different shades of pink. While she was at school I painted her room pink, the furniture was delivered and I put it together and hung the curtains. When she came home she was elated with her birthday surprise and really loved her pink room.” Bud Lauck, Eva said, didn’t arrive home till dinnertime.

In “Blackbird” Jennifer’s father is home when she returns from school and is greeted by the pink room. “Surprise,” he says. “What do you think?'”

Daddy says he picked the whole set out himself, with a little help from Deb, and he put the whole thing together too.

Eva can only speculate about Jennifer’s motives in depicting her as unrelentingly cold. “I don’t know if she’s matured beyond that kid back there … Jennifer’s identity, it seems she’s clinging to this poor victim who was mistreated. What else is she? Isn’t she a mother and a member of the community, and doesn’t she vote? Is there nothing else in her life?”

“This girl knows no shame,” Lantry said. “What she writes about a family that took her in. I don’t want to hurt Jennifer, there’s been so much pain. But I can’t let these falsehoods be left as truth.” He added, “She really doesn’t have much of a defense.”

Lauck, not surprisingly, sees the situation differently. In February, Lantry and Lauck spoke for the first time in 26 years. Lantry had discovered “Blackbird,” and read it. He tracked Lauck down in Portland, Ore., through, he said, her psychiatrist. According to both of them, the conversation was cordial enough. Lantry says they talked about Bud Lauck’s death, and that it was a very emotional conversation. Lauck says Lantry “wanted to have extensive conversations about his memories of my dad.” She added that Lantry was “very sympathetic, very apologetic — repeatedly apologetic — ‘We were awful to you, it’s always just tormented me, how awful we were, how awful my mother was to you’ — and how tortured he felt about many things.” Lauck describes Lantry as “very deeply disturbed about his own childhood and he clearly needed to talk.”

Then Lantry rang up again in September. That time their conversation was not cordial. Lantry recalls telling Lauck, “I’m going to rebut some of the statements you made in ‘Blackbird,’ unless you’re willing to reclassify this as historical fiction.” He said Lauck “started screaming and yelling, and she threatened she’d reveal to the world that my mother killed her father.” “Are you going to deny an 8-year-old child her reality?” he recalls Lauck shouting. “Then she slammed the phone down,” he said.

Asked about this exchange, Lauck said, “This is a guy who’s been systematically abused by his mother and the church. He may have interpreted my conversation with him as yelling. I may have said, ‘Well, what the hell are you talking about?’ I can’t recall the specifics. It was of a personal nature. Whatever he wants to say I said, that’s fine.”

“It wasn’t until later when I read the book again that I started thinking, ‘Something has to be done,'” Lantry says. So he rounded up all the reviews of the book and started sending e-mails to the reviewers, asking them why they didn’t question the veracity of Lauck’s story. He reckons he sent between 20 and 25 e-mails, some of them to reviewers on Amazon.com. “I also left a couple of messages on [Oprah’s] e-mail on her site,” he says. He says he got in touch with another talk show (he declined to say which one) by tracking down a producer through Google.

As for Lantry’s “campaign,” as Lauck put it, nothing will change. “I wrote a memoir based on my memory. Not a collective memoir. Memoir. And I don’t expect anyone to come up and say, ‘I completely agree 100 percent’ — certainly not people who victimized me and hurt me,” she said. “This is not a surprise. I suspected it before I wrote it. But it was vetted with my publisher and with the attorneys that I worked with, and with my agent, and it was a long and careful process that I feel very comfortable with — which I explained to him. And I said, ‘Look, you have to do what you have to do. I don’t know what you really want from me. I don’t need to have a relationship with you, and I wish you well. I just wish you away from me.”

Lauck declined to speculate on the reasons for Lantry’s zeal. “I just wish him to go on with his life and hopefully find some peace,” she said. “Because it certainly seems like he’s having a very difficult time. I think it’s a waste of living. And that was the whole point of writing “Blackbird” and “Still Waters,” to have an understanding of a complex past and place that you could move forward from and learn from. Which is what I’ve done.”

Some from her past would disagree.

Zve Hare was 7 years old when she met Jennifer Lauck. Hare and her mother and brother boarded in a large house Eva rented in the Westlake district of Los Angeles, and Zve was also part of a small day-care group Eva ran. Jennifer Lauck met Hare when she moved into the boarding house with her father and brother some time after Janet Lauck’s death. In “Blackbird,” a character named Zve is the daughter of a couple who live in the group house where “Deb” abandons Jennifer.

Hare also says she hasn’t read “Blackbird.” She says she read a couple of interviews with Lauck, including the Willamette Week article, and “found her attitude to be really disturbing. Of course, it could be taken out of context. But she was so martyrlike. She wants everyone to believe she’s the big victim in the world and everyone else is the bad guy, and it’s just impossible. It’s never true everyone else is against you. Her attitude seemed very unbalanced about her victimhood. It made me understand why Jonathan is taking issue with this.”

Particularly irksome to Hare was Lauck’s portrayal of Eva. “I find it disturbing and upsetting that she is failing to recognize the more complex reality of a person in, say, Eva’s position — she was a very good woman having a really hard time, doing her best. She was not an abandoner. She would never abandon a child. She couldn’t have taken such good care of us [in the day-care center] for years if she were.”

Hare’s mother, Heidi Lockwood, was friends with Eva, whom she described as “a kind person but not very warm. She had this detached quality. She had to be very strong because she was responsible for her children. She was a very tender person. If there was something hard to deal with, she’d become more detached. She was world-class, and she was funny.”

According to some of Eva’s acquaintances, she had been physically abused by an ex-husband she left in the Midwest.

“The value in telling your childhood story is in bringing your adult awareness and sympathies and ability to look at things from different points of view, to really explore it,” Hare said. “What can we learn from a memoir that tells us over and over how bad other people were?”

Hare said Lauck took liberties in depicting her, “but I don’t own the name [Zve].” She also challenged the veracity of Jennifer’s account of dragging her furniture for 11 blocks.

“I lived at that house at a later time,” Hare said. “It was two buildings down.”

One member of the Lauck family who appears under a pseudonym in “Still Waters” received a telephone call from Lauck when she was researching “Blackbird.” “She called me one time and she asked me flat out, Did her father have an affair with Eva before her mother died? I said no. What Bud had said was that after Janet died, he needed to find some arrangement to help him take care of the kids. He moved himself and the kids into an old Victorian boardinghouse. Eva ran it. Over time they got to know each other and began to have a dating relationship. I told Jennifer that, and she still wrote that they began having an affair before Janet died. Why would she portray herself as loving her father so much and then tell the whole world that he was having an affair before her mother dies? That made me angry.”

“Still Waters” was even worse. “I was just utterly disgusted,” the family member said. “She paints Margaret [one of Lauck’s aunts] as a very unhappy woman with a wild temper, and very cold, and that’s not the person I know at all.”

Lauck’s cousin Paul, a 32-year-old firefighter in Texarkana, Texas, was also contacted by Lauck during the course of her research. Lauck’s brother, Bryan, had lived with his family, and Paul feels that Lauck’s depiction of his parents in particular was unduly harsh. “Aunt Sylvia [the name Lauck uses for his mother, Ruth] never having said she loved Bryan is absolutely not true,” he said.

But as far as Lauck is concerned, she doesn’t need to defend herself, period. “Just because they say it’s so doesn’t make it not true on my part,” she said. “I mean, I have written a book, and I have done the research, and I have a publisher and a legal team, and an agent, and I’ve worked my rear end off here. And here’s a guy [Lantry] disagreeing with me, and basically because he’s disagreeing, that becomes truthful. I don’t wish any of his family ill, that’s why I changed their identities, that’s why I made geographical changes, that’s why I did everything I could to protect rights of privacy — not just of myself but of them.” Furthermore, she added, she went easy on everyone, downplaying their abuses.

The author declined to discuss individual alleged inaccuracies, saying, “I’m just not going to get into specifics because it’s not relevant to the larger story.”

Still, after Lantry brought his concerns to her attention, she said, she looked into some of them. For instance, she said, she went down to Los Angeles and surveyed the area of the furniture-moving episode. And? “I’m not going to go into specifics,” she said. “My whole desire was to convey a sense of having moved something a distance. I wrote it fairly and accurately.”

So if a reporter retraced the same steps, would she find that the number of blocks in “Blackbird” — 11 — is true? “I don’t know what you’d find,” Lauck said.

What other things did she recheck? “I’m not going to talk about that,” Lauck replied. “I don’t think that’s required of me. I’m not comfortable going through a specific reaccounting of how I wrote my story, and how I investigated, or what documentation I have, or blah blah blah. That’s a tedious conversation that gets away from the heart of the fact that this is the memory of a little girl, and I wrote it to the best of my ability, and I stand behind it 100 percent.”

Such a response is unlikely to satisfy her stepfamily. Given the gravity of his claim, why isn’t Lantry or his mother suing for libel?

Eva says she’s only bothered by the matter because her son is. “Jonathan is being my champion,” she wrote in an e-mail message. “He is incensed that his mother is slandered … But I don’t have guilt about her charges because they didn’t happen.”

“There are a lot of good reasons for people who feel they’ve been libeled not to bring a lawsuit,” said a lawyer at a major publishing house. “For example, the litigation itself may draw more attention to the very statement they are disputing. In a case where family names have been changed, the hesitancy might be more pronounced.”

“I would personally never file a lawsuit,” Lantry said. “My mother would never file a lawsuit. I could see Jenny hitting me with a lawsuit.”

What does Lantry want? “To whatever extent I can achieve it, I want equal time, enough exposure for people to see someone raising a reasonable doubt,” he said. “I have a child,” an 18-year-old daughter. “I don’t want this to go down as familial history.”

Then again, media exposure, like litigation, has its own way of shaping familial history. Lantry said he’s in touch with a talk show but would appear only if he could get four of the Laucks to join him. “I’m looking to achieve parity of exposure,” Lantry said. “This is not a crusade.”

Lauck’s editors at Pocket Books did not return calls seeking comment.

Unless libel comes calling, it’s unlikely a publisher would not stand behind an author. And fiction in memoir is nothing new. “It’s a consensual hallucination,” says Ethan Nosowsky, an editor at Farrar, Straus & Giroux. “We’ve all agreed not to say there’s fiction in a memoir. If a writer lays claim to the experience as autobiography, then we’ll publish it that way.”

Categorizing a book as nonfiction helps tremendously in its publicity campaign because it allows the author to talk about personal experience with the press. As Elizabeth Beier, an executive editor at St. Martin’s Press, explains, “If you call it fiction, you couldn’t see an author saying, ‘Oh … a lot of the fictional characters in these experiences were real.'”

As far as Lauck is concerned, “Blackbird” is “a story about a larger human experience,” not about “paperwork. Children feel lonely, children feel lost, and they feel confused,” she said. “I wanted to portray my experience based completely on this little girl, real time, what she’s going through — not breaking it all down to ‘Here’s this document that proves this fact.’ I’m very proud to have been that little girl. I’m quite amazed that I am that same child sitting talking to you here right now, I’m like, Wow, I can’t believe I survived that.”

What does Lauck have to say about the brouhaha her stepfamily is raising? “An option could be that I could write this as fiction, and an option could be that they write their own memoirs,” Lauck says.

As it happens, Lantry is working on a book about the first generation of children growing up in a cult society.

In the meantime, his mother says she will not be reading “Blackbird.” “I don’t really care,” she wrote in an e-mail. “My life is so much more than that. I like my life. I like me. I like other people. I like Jennifer. I do not consider Jennifer the enemy at all. I wish Jennifer well.” Nevertheless, Eva does not expect Lauck to do “the honorable thing” and reclassify her work.

She wrote, “It would be nice if all humans told the truth, including me.”

Maybe her wish will come true. Jennifer Lauck is working on a novel.