After a brief meeting with his National Security Council, President Bush strode into the Rose Garden Thursday morning to announce the United States’ withdrawal from the 1972 Anti Ballistic Missile treaty with Russia. This, he said, would allow the military to “develop ways to protect our people from future terrorist or rogue state missile attacks” — namely, a National Missile Defense.

Various forms of disapproval were voiced around the globe. In Beijing, according to the Xinhua News Agency, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Zhang Qiyue said that China opposed the U.S.’s plans for a National Missile Defense and is “concerned” about the latest move. In Moscow, Russian President Vladimir Putin called the decision “a mistake” and, according to TASS, Colonel-General Leonid Ivashov said that the U.S. withdrawal from the treaty “shows that it is boosting its efforts towards establishing dictatorship aimed to use military force in the world,” and that the “U. S. national missile defense system may pose potential threat for Russia’s security.” Sen. Joe Biden, D-Del., chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, called the decision “a serious mistake.”

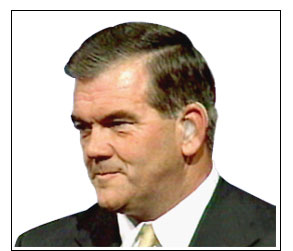

But the former leading Republican opponent of missile defense, the man who co-authored an Op-Ed referring to missile-defense hopes as “a lot of dreaming,” had no comment. Perhaps that shouldn’t come as a surprise, considering his new gig. How would it look if a critic for the president’s most ambitious plan for the security of our homeland was Tom Ridge, the director of the office of Homeland Security?

Throughout his career as a Republican member of the House, Ridge was the leading Republican critic of what was then called the Strategic Defense Initiative. And though today’s National Missile Defense differs somewhat from the SDI proposals Ridge led the charge to contain, many of the same criticisms being made against the technology today could have been — and in some cases, were — made by Ridge.

Neither Ridge nor his office returned a call for comment.

“His record was similar to my own,” recalls former Rep. Charlie Bennett, D-Fla., Ridge’s partner in containing SDI funding during that era. “It was approving the idea of going ahead with studies — as was allowed by that treaty — but critical of the idea of going ahead” as far as missile defense proponents wanted, which would have necessitated withdrawal from the 1972 agreement. Ridge and he never opposed missile defense research, Bennett says, but they didn’t feel that the technology at that stage supported “com[ing] to a point where we would break a treaty — when we weren’t that far along.”

There have been technological advances in missile defense technology since the 1980s and early ’90s, when Ridge and Bennett worked hand-in-hand to cut SDI funding. Though as recently as August, even after the successful July test of the hit-to-kill technology, Air Force Lt. Gen. Ronald Kadish, director of the Ballistic Missile Defense Organization, told reporters that it was “still not totally comfortable for me to say that we can make the hit-to-kill technology work consistently. We still need some more reliability in there.”

After a successful Dec. 3 test, Kadish sounded more positive. “This was an important achievement,” he told reporters. “It means we can take the next step and make the tests more complex.” Missile defense critics noted that while in three out of the last five tests interceptors had hit their mock warheads, they did so only under optimum conditions.

So for missile defense detractors, like Biden, the arguments are essentially the same now as they were when Ridge railed against it. Missile defense is “a fantasy of some system that remains more flawed than feasible,” Biden said in his ill-timed speech against missile defense at the National Press Club, on the afternoon of Sept. 10.

In 1989, Ridge secured the support of 20 of his fellow moderate Republicans for a Bennett-Ridge amendment that reduced SDI research funding almost $2 billion from the $4.9 billion requested by Bush’s father, then-President George H.W. Bush, to $3.1 billion. A year later, Ridge and Bennett reduced that figure even further, to $2.3 billion. Ridge was one of only 11 in his party to support a 1992 amendment by then-Rep. Dick Durbin, D-Ill., to skim off another $1 billion from SDI coffers.

“We cannot afford to waste critical defense dollars on a crash program of unproven technologies when we have other programs that are more than lean,” Ridge said on July 25, 1989. “Many of our conventional programs are being starved to death by this need to find an immediate fix. My colleagues, we must pursue the SDI fix, but keep in mind that the fix will not be immediate, no matter how many dollars we throw at it.”

At the time, he incurred the wrath of his more hawkish peers. “I hope we never have to say, ‘I told you so,” said then-Rep. Bob Dornan, R-Calif. “When the city of New York is eliminated from the planet; or fighting some diabolical germ of biological warfare set loose in that city by one missile with one evil cone in that missilehead sent from somewhere in the Middle East.”

Bennett says that Ridge — his “pal” and “partner” — isn’t necessarily caught in any sort of contradiction despite the fact that he’s head of a homeland defense that in no small way intends to rely upon technologies he once criticized as unrealistic. “Times have changed,” Bennett says, allowing that since retiring from the House in 1992 he hasn’t paid much attention to the advances in missile technology. “If now as a result of the studies they’ve made they indicate a greater chance of success than was true back then, then it ought to be approached from that standpoint.” He and Ridge never opposed missile defense per se, he insists, they just “raised questions about the program.” And as for Ridge, “He may have information he didn’t have when it was presented before. So he can respond to any change that has occurred, or even change that has occurred in his thinking.”

In a 1989 Op-Ed for the Christian Science Monitor, Ridge and Bennett wrote that “there is growing consensus that neither our technology nor our finances can support deployment of SDI. The question for President Bush and Congress is: How do we resolve this issue which has generated such ardent emotions?” Following the advice of SDI supporters, Ridge and Bennett wrote, would “mean breaking out of the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty and would start a new arms race with the Soviet Union.”

On Thursday, that sentiment was echoed by Carl Levin, D-Mich., chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, when he said that “unilateral withdrawal will likely lead to an action-reaction cycle … and that kind of arms race would not make us more secure.”

Ridge and Bennett continued on in their Op-Ed: “Arguments about SDI have consumed too much time. They have obscured the real challenges the US confronts, including the need to improve conventional forces to deter the most likely kinds of war. A huge budget for SDI is simply not sustainable when this country confronts severe crises in trade, banking, nuclear arms, and conventional forces.”

This is the same argument Biden made at the Press Club. “Our priorities, I think, are a little out of whack,” he said. “I’ve said, and I’ll say it again, we should be fully funding the military and defending ourselves at home and abroad against the more likely threats of short-range cruise missiles or biological terrorism.”

Ridge’s opposition to SDI was not all that unusual. As a congressman — representing the Democratic-leaning area of Erie, Penn., from 1982 until 1994 — the Vietnam veteran was somewhat doveish on defense issues in general, opposing aid to the Nicaraguan Contras, voicing support for a nuclear freeze, voting to abolish the first-strike M-X missile. In 1989, against the wishes of then-President George H.W. Bush and then-Defense Secretary Dick Cheney, Ridge voted to halt production of the very B-2 stealth bombers used during the first strikes in Afghanistan.

But it was Ridge’s opposition to missile defense where he wasn’t just a voter, but what the conservative National Review referred to as “a leader in the enemy camp.” When Secretary of State Colin Powell was pushing for Bush to name Ridge secretary of defense in December 2000, conservatives rallied against the idea because of his perceived liberal record on defense issues. “I don’t want someone with those views in a position such as secretary of defense,” Sen. Jim Inhofe, R-Okla., told the conservative magazine Human Events. Echoed Eagle Forum’s Phyllis Schlafly: “I can’t think of any single issue that would be more of a litmus test [for defense secretary] with Republicans than SDI, one of Ronald Reagan’s most important legacies.”

In an interview with the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in August 2000, Ridge groaned at the charge. “A dove? Please,” he said. “The fact that I voted for the second-highest amount and not the highest amount for SDI somehow made me a dove?”

Not necessarily. Today’s missile skeptics, like Biden and Levin, don’t consider themselves doves. Like Ridge, they continue to support funding missile defense — at a lower rate than what Bush (both father and son) seek — until the technology is proved more promising.

But there is one significant difference between the missile defense skepticism of then-Rep. Ridge and the current critics. Earlier this year, Levin led the Democrats on the Armed Service Committee to reduce $1.3 billion from the $8.3 billion Bush had requested for the 2002 budget. After Sept. 11, Levin and the other Senate Democrats restored that funding. Ridge, therefore, was not only a more effective missile defense opponent, he was also more consistent.