“Mirroring Evil,” the exhibit of Nazi imagery in recent art that is now at the Jewish Museum in New York, was greeted with enough scandal-mongering hysteria before it opened to assure both big crowds and protesters at its March 17 opening. Featuring art that, in the words of curator Norman Kleebatt, “puts the viewer in the uncomfortable terrain between good and evil, seduction and repulsion,” the show is being called the Jewish “Sensation,” in reference to the 1999 show at the Brooklyn Museum that featured Damien Hirst’s vivisected livestock and Chris Ofili’s Virgin Mary adorned with shellacked elephant dung.

The surface analogies between the two are obvious enough. On one side are outré artists and earnest curators steeped in the history of transgression. On the other are shocked religious leaders and politicians outraged that community spaces are being used to assault community sensibilities.

Some sensibilities are clearly taking a beating. There have been reports of Holocaust survivors sobbing as they stood before the art. Menachem Rosensaft, head of The International Network of Children of Holocaust Survivors, has called it “a desecration,” adding that the show “is a glorification of evil and as such it is simply unconscionable.”

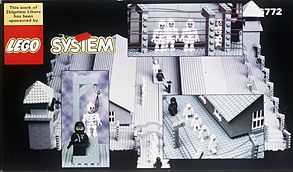

It’s easy to see why they’re furious. Among the works in “Mirroring Evil” are Tom Sachs’ “Giftgas Giftset,” three cylinders designed to look like canisters of Zyklon-B — the cyanide gas used to kill Jews and others in the Nazi death camps — and adorned with the labels of Tiffany, Hermes and Chanel. There’s also Alan Schechner’s “It’s the Real Thing — Self-Portrait at Buchenwald,” a computer-manipulated image that puts the artist, well-fed and clutching a can of Diet Coke, amid emaciated, shell-shocked survivors; and Zbigniew Libera’s self-explanatory “LEGO Concentration Camp Set.” Compromising with its critics, the uptown Manhattan museum has walled off some of the more outrageous works and installed signs warning viewers about their disturbing potential.

Yet for all the strife, “Mirroring Evil” is not “Sensation,” and not just for the reasons the Jewish Museum has pointed out in a handy press guide for telling the two controversies apart. The sensation over “Sensation,” like previous battles pitting art-world enfants terribles against fulminating philistines, was a variation on a theme that dominated American culture in the ’90s: the unbridgeable aesthetic and moral divide between the avant-garde intelligentsia and the religious right. Such events usually pitted outsiders — gays, women, blacks, sneering Brits — against the ostensible spokespeople for solid American values.

“Mirroring Evil” is different. It represents a flashpoint in another kind of culture war, one that’s bubbling within the Jewish community. It’s a struggle over the meaning of Jewishness, over the lessons that should be drawn from a terrible history. For the generation who lived through the Holocaust and that immediately after, the Nazi genocide has become the defining factor in Jewish identity. It’s seen as a horror almost metaphysical in its uniqueness. Its victims are martyrs and representations of their suffering are sacred. That’s why it was considered extraordinarily daring when Art Spiegelman’s graphic novel “Maus” portrayed a survivor as a racist, stingy man.

Yet a younger generation of Jews, most of whom grew up unscathed by anti-Semitism, is disputing the idea of perpetual victimhood and the political pieties that accompany it. “Our duty is to let Jewish artists ask us the next level of questions, which are going to percolate up anyway,” said Kleebatt during the press preview of the show. “One thing is evident in artists of this generation,” he added. “They know more about the Holocaust through pop culture, film and TV than through serious educational initiatives. Some of the images have become depleted of their power through overexposure.”

Kleebatt mentioned filmmaker Todd Solondz, whose recent movie “Storytelling” mocks what might be called the Holocaust chic of comfy Americans who exaggerate their connection to genocide in order that some of its saintly dignity might rub off on them. In a similar vein is a piece from the Jewish zine Heeb (itself lambasted by some of the forces opposed to “Mirroring Evil”), which satirizes the paranoia of the Jewish establishment by arguing that Pizza Hut’s Twisted Crust Pizza is a secret SS plot.

“Mirroring Evil” is less about the Holocaust itself than about representations of the Holocaust, and the ways they have trivialized and eroticized systematic slaughter. It’s two steps removed from the devastation, which is part of what accounts for its controversy. “The cool hits the hot,” says Kleebatt. “Twenty years ago, art about the Holocaust was redemptive. This group of artists is saying that it is not a subject that can be redeemed. It’s using intellectual, conceptual art to confront very emotional issues.” The art suggests both that the solemn awe once accorded to representations of the victims is breaking down, and that, even for Jews, evil’s perverse appeal hasn’t been vanquished by all our memorials.

This is a generational issue, as even Abraham Foxman, the national director of the Anti-Defamation League and a vocal critic of the exhibition, has implicitly admitted. Arguing that the Jewish Museum should hold off on “Mirroring Evil,” he says, “I’m not saying forever and ever, I’m saying not now.” Such a show might be acceptable “in another generation, when survivors will not be hurt, offended, slapped in the face. We can postpone it. I’m not saying it should never be done.”

Of course, if Foxman believed that the exhibit truly degraded survivors, there would never be an appropriate time or place for it at the Jewish Museum or anywhere else. But the problem isn’t that, exactly — it’s that the show threatens the cherished verities that have helped survivors cope with near-annihilation.

“Mirroring Evil” represents the latest challenge to the kind of American Holocaust myth-making that Peter Novick identified in this 1999 book “The Holocaust in American Life” and that Norman Finkelstein excoriated in his 2000 “The Holocaust Industry.” Though wildly different in tone, both books critiqued the way American Jewry has treated the Holocaust as something so unfathomable that it transcends history and thus eludes comparisons to other atrocities.

Novick writes, “Jews were intent on permanent possession of the gold medal in the Victimization Olympics,” concluding that the “memory of the Holocaust is so banal … precisely because it is so uncontroversial, so unrelated to real divisions in American society.” The Holocaust isn’t used by Jewish organizations to demand action preventing other genocides — rather, mainstream Jewry contends that it trivializes their suffering to compare Bosnia or Rwanda to Hitler’s charnel houses.

Meanwhile, professional survivors in America have created endless museums and education programs that take the uniqueness of Jewish suffering for granted. They’ve also created a whole host of advocacy organizations whose fundraising depends on keeping the memory of the Holocaust alive. It has indeed become an industry — as former Israeli foreign secretary Abba Eban quipped, “There’s no business like ‘Shoah’ business.”

That’s what many of the artists in “Mirroring Evil” are working against. They’re pointing out the way Holocaust images have been turned into kitsch, and at the same time revealing how fascist aesthetics have crept into our culture while Holocaust caretakers like Elie Wiesel were busy at the opening of yet another memorial. It’s no wonder those caretakers are livid.

Alan Schechner, who cites “The Holocaust Industry” as an inspiration, has been accused of trivializing the Holocaust, but his work is actually a sustained critique of the trivialization of the Holocaust by institutions from the Yad Vashem museum and memorial in Jerusalem to Steven Spielberg. One of his most trenchant pieces (not included in “Mirroring Evil”) is “6,000,000,” a video in which the murder of a little girl in “Schindler’s List” is looped 6 million times — it takes about two years to play. It demonstrates how Spielberg’s film, despite making claims for itself as a historical document instead of a mere Hollywood movie, can’t begin to approach the enormity of the Nazi extermination. “It’s the Real Thing,” which is one of the images being used to signify the depravity of the exhibition as a whole, is a work about exploitation, and the impossible guilt of a well-fed contemporary Jew trying to imagine the pain of his relatives.

Schechner has been painted as an enemy of the chosen people, but in reality his Jewish credentials are impeccable, and not just because much of his family perished in the camps. An Englishman, he voluntarily moved to Israel as a teenager to serve in the army, and spent a total of eight years in the country. He was involved in the invasion of Lebanon and served in the Palestinian occupied territories.

The experience radicalized him, making him see that “Israel wasn’t the light unto the nations that it sometimes claimed to be.” He came to believe that the Holocaust was being manipulated to serve an expansionist military ideology. On the phone from his home in Savannah, Ga., where he teaches at the College of Art and Design, Schechner noted how former Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin once justified the Israeli invasion of Lebanon by saying that it was to prevent another Treblinka. Schechner talked about how visiting foreign dignitaries are immediately taken to Yad Vashem, thus framing all discussion about current events against a backdrop of Jewish persecution.

“Israel is a small country surrounded by enemies, but it is the military superpower of the region,” Schechner says. “The discourse made it seem like we were in the Warsaw ghetto, doing everything we could just to survive, when the reality was expansionism and the longest military occupation of this century. I was hit by the way the sacredness of the Holocaust was being blatantly manipulated.”

His initial feeling, he says, was to ask, “What right have these people got to manipulate these images for their own ends? It’s very much the response people are giving me now. What I wanted to do with the self-portrait piece was to make the manipulation explicit.”

Like Kleebatt, Schechner wanted to start a dialogue within the Jewish community about the use of Holocaust imagery. Instead, he’s faced with something like cultural excommunication; not only his art but also his Jewishness have been attacked. “Elements of the Jewish establishment aren’t open to dialogue and diversity of opinion,” he says. “Any criticism of Israel immediately makes you some kind of self-hater.”

Schechner, who is 39, is just one of many younger Jews alienated by organized Jewry’s political hegemony and single-minded focus on Jewish persecution. “I’m very critical of the Jewish community harping on this fear of anti-Semitism,” says Jennifer Blyer, the 26-year-old editor of Heeb. “It has diverted them from focusing on real issues of social and economic justice that affect everybody.”

Danya Ruttenberg, editor of the recent Jewish feminist anthology “Yentl’s Revenge,” adds, “A lot of people today are rebelling against the Jewish establishment. Partly it’s that in the Jewish establishment, to make a hideously sweeping generalization, there’s still a lot of talk of victimhood. Many of the structures of institutional Judaism were set up when they really were out to get us.”

But they’re not anymore, at least not in America. And that’s at the heart of the generational clash around “Mirroring Evil.” For older Jews who will always experience their position in the world as precarious, the role of a culturally specific institution like the Jewish Museum should be to close ranks around the victims. “I expect a certain level of sensitivity, understanding, reverence from the Jewish Museum,” says Foxman.

It’s only a generation that is removed from the horrors of the camps and from religious ostracism that feels safe enough to be irreverent with the images that support institutional Judaism. “Those inside the Jewish establishment believe they know exactly what the Holocaust means,” says 44-year-old Rabbi Irwin Kula, president of the National Jewish Center for Learning and Leadership and a vocal supporter of the exhibition. “It means we’re the good guys, and they’re the bad guys, we’re the victims, they’re the killers, we’re the needy recipients of empathy, they’re the people that need to be forgotten. It means we’re pious and holy,” he says. This visceral conception of history is valid when it comes to the Nazis. But as a way of understanding Jewish life six decades after the Holocaust, it’s grown stultifying.

“Who wants to say we’ve spent hundreds of millions of dollars on Holocaust museums [and] all of those images are so hackneyed and banal that they don’t move us anymore?” Kula asks. “When you see the victims’ bodies they should actually outrage you, but let’s face it, they don’t. You look at the victim, remember the evil, you pass judgment on some distant event and you forget that the potential for evil, small or large, is within us. This is the untold secret.”

He continues, “I love the Holocaust Museum [in Washington]. It’s a sacred place. But let’s be honest. People do the pilgrimage to it, they cry, then they go out to eat that evening. It doesn’t affect anything. It doesn’t create empathy. It creates sentimentalism.”

Even more than that, an institution like the Holocaust Museum (officially, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum) may seem to exempt Jews — and those who empathize with their undeniable historical suffering — from examining the allure of fascism. Some of the best art in “Mirroring Evil” is designed to highlight just how acceptable deracinated Nazi imagery has become. Even as the language and imagery of victimization has been bled dry by promiscuous overuse, Nazi images have been glamorized. Piotr Uklanski’s extraordinary “The Nazis” lines the walls with 166 photos of seductive movie stars from Ralph Fiennes to Frank Sinatra to Marlon Brando, all looking dashing in their SS garb. All appear so handsome and commanding it’s hard not to feel that some unconscious admiration is at work in their depiction.

Maciej Toporowicz’s illuminating video “Obsession” juxtaposes scenes from Leni Riefenstahl’s propaganda films and sculptures by Hitler favorite Arno Breker with Nazi-inflected art-house S/M from the ’60s and ’70s and Calvin Klein ads from today. Set to a pulsating electronic score, the images blend into each other in a way that’s sexy, horrible and disorienting. It’s a visual riff on Susan Sontag’s famous essay “Fascinating Fascism”; the old films he uses are the same ones she discusses. Alarmingly, everything Sontag says about fascist art is true of Toporowicz’s contemporary images.

“Fascist art displays a utopian aesthetics — that of physical perfection,” Sontag writes. “Painters and sculptors under the Nazis often depicted the nude, but they were forbidden to show any bodily imperfections. Their nudes look like pictures in physique magazines: pinups which are both sanctimoniously asexual and (in a technical sense) pornographic, for they have the perfection of a fantasy.”

The men in Calvin Klein’s ads, perfectly sculpted amid imposing Teutonic architecture, seem interchangeable with Becker’s sculptures or Riefenstahl’s shots of model Aryan athletes. Kate Moss, emaciated and supine, merges with images of girls being stripped and spanked. “Obsession” is hypnotic, and it makes one wonder at the way we’ve been internalizing the Nazi cult of physical perfection even as we chant the litany “never again.”

Of course, there are 13 artists represented in “Mirroring Evil,” and their messages aren’t uniform. Several of the artists aren’t even Jewish, though by including them, Kleebatt makes them part of a Jewish debate. Yet out of the 13, only one could credibly be charged with trivializing the Holocaust. While many of the artists in the show use pop culture to reflect on our understanding of Nazism, New York artist Tom Sachs, creator of “Giftgas Giftset,” attempts to use Nazism to underscore a juvenile take on consumer culture.

It’s an important distinction. Artists like Toporowicz and Schechner are concerned with the way Nazism is manipulated. Sachs, on the other hand, seems to want to compare the coercion exerted by high-end brand names like Prada to being interned at Dachau. As he said in a spectacularly stupid interview with the New York Times Magazine, “I’m using the iconography of the Holocaust to bring attention to fashion. Fashion, like fascism, is about loss of identity. Fashion is good when it helps you to look sexy, but it’s bad when it makes you feel stupid or fat because you don’t have a Gucci dog bowl and your best friend has one.”

Yet Sachs’ shallowness is the exception here, and the comparison serves to underline the moral seriousness of many of the other artists in “Mirroring Evil.” One hopes that some of those protesting the exhibit will actually talk to artists like Schechner. As Kula says, “The people who agree on this are the Holocaust survivors and the artists,” although the survivors may not realize it. “The artists are outraged by the trivialization. The people who don’t understand are the Holocaust industry people, because their lifeblood is based on a single interpretation and the institutional power and budgets that go with it.”

There’s a difference between showing disrespect to that powerful and entrenched Holocaust industry and to the hideous historical calamity of which it claims ownership. Most of the artists in “Mirroring Evil” are trying to honor the injunction “never forget,” but with the knowledge that what they remember is now no more than a reflection.