Of all the people acquiring guns in 1998 on the black market in Ljubljana, Slovenia, Charles Krafft was probably the only one who turned the illicit weapons into porcelain delftware.

Meeting with arms dealers in Ljubljana’s cafes and bars, Krafft made arrangements to borrow Kalashnikovs and AK-47s (“the little black dress of the military industrial complex,” he calls the assault rifles) so that he could use them to make plaster slip-molds. He then created meticulously accurate castings of the guns in white porcelain and painted the weapons with flowers, text and other decoration in the traditional delftware blue. The resulting collection of lethal but dainty satire became part of a body of work that provoked Mark Del Vecchio, author of “Postmodern Ceramics,” to declare Krafft “one of the USA’s most seditious artists [who] plays difficult, uneasy games with content and culture.”

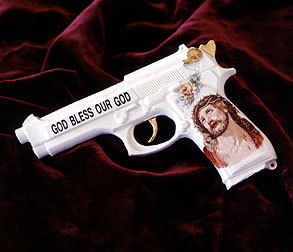

At 54, the seditious artist — also a celebrated painter, writer and scalawag — has expanded his fine-china arsenal to include Thompson assault rifles, Uzi and Intratech machine pistols, Beretta and Smith & Wesson pistols, 50mm machine gun rounds, switchblade knives and hand grenades. His intention, he says, is to produce “life-size ceramic weaponry so gorgeous and patently functionless that it will bedazzle and confound everyone who sees it.”

The lampoonery has terrific resonance at a time when terror threatens at the periphery of everyday life. But Krafft admits to no political or spiritual leanings — he doesn’t suggest that his art is meant to teach a lesson. His interest, as a nonbeliever, he says, is in the power of belief systems to compel people, often very intelligent people, to risk their lives, or at least their reputations, to achieve “some sort of spiritual or political liberation.” And while his jocular explorations of human catastrophe may make those who share his dusky sense of humor chortle, they also force the viewer to look at mankind’s cruelest, most absurd behavior in a way that penetrates the numbness induced by media overload.

Next, says Krafft, he’d like to make full-size Scud missiles and nuclear bombs in pure white porcelain. Recently he’s been consulting with a police firearms investigator who’s assisting him in developing a “Man Ray Gun Chess” set to be cast from ammunition.

“I’ve always wanted the same response, ever since I was a kid, before I was an artist,” he says. “I don’t want to offend people, but I want to shock them into seeing differently. It has a lot to do with humor; I think that humor’s really important to keep you healthy. And in art there doesn’t seem to be enough of it.

“For some reason,” he continues, “art has to be this earnest, serious, even Freudian, exploration. But it doesn’t necessarily have to be that at all. Art that’s funny seems to get dismissed just because it is funny. But I’ve always had a knack and a penchant for going toward humorous irony. I can’t control myself, I really can’t put the brakes on.”

To hell with the brakes, lately Krafft seems to have both feet on the accelerator. After painting on canvas for 20 years, he took brush to porcelain and found himself the center of enormous attention. “The moment I went from easel painting to ceramic painting,” Krafft says, “was the moment that the world started to take notice of me.”

Krafft now has two one-man shows running concurrently — one at the Grand Central Art Center in Santa Ana, Calif., the other at the Copro/Nason Gallery in Culver City, Calif. His work also has been shown recently in New York and Europe, featured in the New Yorker, Harper’s and Artforum and included in several books. Later this summer a volume focused entirely on his art, titled “Villa Delirium,” will be published by Last Gasp. Krafft is also a member of that small, elite group of artists whose work has been covered by Mortuary Management magazine — more about that later.

Like Krafft himself, the odd and winding story of how all this came about and where it’s led — the “Porcelain War Museum,” which is what he calls his ongoing ceramic weapons project, is but a recent chapter — is equal parts strange, refreshing and funny.

The idea for ceramic weaponry grew out of a trip Krafft made in 1995 to Eastern Europe. A grant he’d received enabled him to accompany the Slovenian arts collective NSK and its industrial rock band, Laibach, on the group’s “Occupied Europe: NATO” tour.

“I’ve always found the lowbrow fringe of contemporary pop culture infinitely more fertile than the highfalutin academic mainstream — I prefer the company of criminals, undertakers and blue-haired ladies,” Krafft told Grand Central Art Center director Mike McGee, who’s writing the introduction for “Villa Delirium.” Later, over coffee near Grand Central, he elaborated. “McGee said I’m one of the most curious people he’s ever met,” Krafft says, “and I agree I’m very curious — in the sense of getting curious about something then immersing myself in it until my curiosity has been sated.”

Krafft and the Slovenian artists and musicians traveled into Sarajevo in U.N. personnel carriers, arriving in the war-ravaged city the day the Dayton Accords were announced. In an e-mail message to a friend at the time he wrote, “The mise en scene of the totaled city certainly lent extra meaning to Laibach’s spooky cover of ‘Sympathy for the Devil.’ You could smell the sulfurs of hell and the stench of death in the snow blowing through the ruins of block after block of shelled hotels, hospitals, homes and shops.”

Krafft later returned to the region to begin work on his porcelain weapons, stopping along the way in Holland where he got a decidedly cold shoulder at the headquarters of a delftware manufacturer he visited in hope of learning techniques. As Krafft later recalled the episode: “It was as though I was asking for human organs or weapons-grade plutonium. It wasn’t until a tattoo artist in Amsterdam’s red-light district put me in touch with a friendly Hells Angel who had completed a rigorous apprenticeship program in a Delft souvenir factory in Gouda that I was finally initiated into the traditional Old World way of painting tulips on teacups.”

Several years before the Porcelain War Museum came about, Krafft had been introduced to painting on porcelain by a group of now-beloved blue-haired ladies. As Krafft later wrote in an article for Studio Potter magazine, his “career in clay began in a suburban breakfast nook [in] … the cozy clubhouse of a gang of sable-brush-wielding grannies who call themselves the Northwest China Painters Guild.” He wanted to learn china painting, he said, “because I disliked clay and all the … sanctimony that seemed to go hand-in-hand with studio potting. For me the whole scene smacked of Orientalism or therapy.”

Krafft sat in on monthly classes led by a woman named Barbara Henderson. “It was all older women, grandmothers,” says Krafft. “It was a kaffeeklatsch kind of thing. They’d talk about their grandchildren and their medical problems. I was the only man. I’d do one kind of china painting when I was with the ladies — ships, windmills, boats on canals, little boys and girls wearing wooden clogs and carrying water buckets — then I’d go home and make Disasterware.”

Krafft’s Disasterware is just what it sounds like: fine china decorated with pictures commemorating disasters — the bombing of Dresden, the sinking of the Andrea Dorea, the explosion of the Hindenberg — all painted in delftware blue. One Disasterware series, “Darkness in Delft,” comprises oval, gold-rimmed plates with the upper half of the oval taken up by a bucolic country scene — villagers ice skating, for example — and the lower half illustrated with a gritty, noir image reminiscent of the photos in old magazines like True Detective.

When he started to show the work, the press took notice, and it’s not hard to see why. The stuff is stunningly effective, wacky and unsettling. By appropriating a kitschy, drenched-in-tradition decorative technique and using it for his own wry reasons, Krafft takes the old, musty and inconsequential and turns it into trenchant commentary on human folly.

“I did this kind of interesting thing with an old prosaic design pattern,” Krafft says. “I gave it a little spin. People are immediately struck by it. It surprises them, I guess. Why would someone depict disasters with floral patterns around it?”

Good question. “What did make you decide to commemorate disasters?” I ask.

“I remember doodling on a cocktail coaster that had a circle printed on it, and at the time the river up north of Seattle, the Skagit, was flooding and there was a lot of news about the floods,” he says. “So, inside that circle I sketched a house sinking into a raging river. And I looked at it and thought, You know, that looks like it would make a good plate. Nobody does that kind of imagery on plates that really indicates the way we actually live now.

“My idea was to drag plate painting kicking and screaming into the 21st century with these images of things you don’t usually find on tableware. It began as natural disasters — like floods — then it went into sociopolitical disasters where,” he says, lowering his voice with mock gravity, “I’ve found the most comfort.”

Before his porcelain work became internationally recognized, Krafft made precise, surrealist paintings, many of which were inspired, he says, by Nikola Tesla. At the same time he would occasionally make fishing lures — from plastic crucifixes. He once rented a large truck, Sheetrocked the interior to transform it into a gallery, installed his paintings inside, along with a nicely dressed young woman to greet visitors — an art stewardess — then had it driven around Seattle (he doesn’t drive, never has). On the side of the truck he hung a sign: “Metropolitan Mobile Museum — Charles Krafft: The Happy Years, 1974-1994.”

In a 1998 article, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer’s critic, Regina Hackett, who called Krafft “the dark angel of Seattle art,” wrote, “What comes across in his art is an aggressive kind of ironic humor applied to various horrors. The deadpan nature of the aggression is what gives the horror a new kind of punch.”

Krafft strikes up conversations wherever he goes and seems to have a knack for running into off-kilter characters and then going off on adventures (or misadventures) with them. He’s traveled widely and frequently throughout Europe and India and he inevitably returns with a raft of strange stories. During the day we spend together his conversation is punctuated with the phrase “Here’s a good story,” and it always is.

This one, for example: One day in Slovenia, Krafft tells me, he came across a college student named Eric who was playing bongos on the main street of Ljubljana. “He had a copy of Aleister Crowley’s ‘The Book of the Law’ down on the sidewalk,” Krafft recalls, “next to the hat that he collected money in, and I asked him why ‘The Book of the Law’ was on the pavement and he said because he was a practicing Thelemite.”

(Thelemites follow the dictum “Do as thou wouldst,” first put forth by the 15th century Catholic monk Francois Rabelais. Crowley, the occult British philosopher and devotee of the black arts whose notoriety peaked in the 1920s and ’30s, had an affinity for Rabelaisian philosophy, which no doubt had something to do with the occultist being embraced anew in the 1960s and later celebrated by Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page among many others. In the ’20s, Crowley and some female followers moved to a house in Italy, which they called the Abbey of Thelema.)

“Then I asked Eric if he knew about the Abbey of Thelema in Cefalu, Sicily,” Krafft continues. “Slovenia is right next to Italy. And he said, ‘Yeah, I spent last summer there. If you buy the gas, I’ll drive you there. I have a semester break coming up.’ Once we’d made the deal, Eric said, ‘Oh, by the way, I’m a junkie. I have a little addiction problem. I’m going to have to go see my doctor and get a week’s worth of methadone.’

“We smuggled his methadone out of Slovenia in the hubcap of the car so he’d have enough medicine to be able to take the trip. Once we got to Cefalu, Eric took me to Crowley’s house. It was abandoned, boarded up, but we went through a window and stayed inside for three nights and three days. I videotaped it and photographed the pornographic murals Crowley had painted, and Eric did a Thelemic ritual, the banishing ritual of the lesser pentagram, they call it. He recited all of these Crowleyian mantras that sound kind of exotic while he stomped around in a circle of candles. I tried to videotape it, but failed because I couldn’t find the low-light button on the camera.”

This is vintage Krafft: While discussing something entirely unrelated, he digresses briefly into 75-year-old porn murals and the strange rituals of a junkie occultist. If bent conversation ever becomes an Olympic event, Krafft’s a shoe-in for the gold.

His trip to Slovenia (he’s now been there several times) ended up having a major impact on the direction of his work and his life. But it also ignited a two-year battle between Krafft and the U.S. government, which the artist won handily. As if it weren’t clear enough that his art is his life and vice versa, Krafft, the proud victor, has chosen to display part of the paper trail from that prolonged bureaucratic wrangle on the walls of the Grand Central Art Center.

Krafft vs. the feds all started when he became intrigued by the projects of the NSK collective, which, he says, tweaks totalitarianism by wryly emulating it. It’s an approach that, like Krafft’s own dark humor, is bound to ruffle the feathers of the irony-impaired.

“NSK’s a collective,” he explains, “that’s declared itself a transglobal, borderless state in time. What that means is that they’re what I call a ‘state of mind’ (they call themselves a ‘virtual state’), and they issue passports to their state of mind. They’re a parasitical state that needs a host state to manifest itself. They appear in a city, open an embassy, then disappear and will reappear — like a traveling virus.”

The grant that underwrote Krafft’s visit to Slovenia called for him to make ceremonial dinnerware for the virtual state. While he was there, “They invited me to come with them to Sarajevo as Laibach’s official tour photographer. They declared Sarajevo an NSK territory and they opened up an embassy in the opera house, hung banners and so forth. And they issued — free — 300 NSK passports in the afternoon to anyone who wanted them.”

Krafft has his special NSK “diplomatic” passport hung on the wall in the Santa Ana gallery, and it does look real at first glance, although on closer scrutiny it’s apparent that it’s not. The fact that there’s no country called “NSK” is the first tipoff. When he arrived back in the U.S. at Detroit airport, Krafft, naturally, was chosen from a 747 full of people for a random search. “I did not present the passport to Customs,” he says. “I just had it in my pocket and they found it when they searched me in this little room where they’d taken me. And when the officer saw it, he said, ‘What entitles you to carry a diplomatic passport, Mr. Krafft?'”

“I said, ‘It’s not a diplomatic passport at all, it’s not even a passport, it’s a limited edition art object and here’s all the paperwork to prove it.’ And then the officer got shitty with me. He said, ‘You can file an appeal of seizure form or I can throw it away in front of you. What do want?’

“He’s thinking I’m going to have him throw it away so I can get my connecting flight to Seattle, which is just about ready to go. But I said, ‘I’ll do the appeal of seizure.’ And for two years I was on them like a fly on shit until they had to give it back to me. I got my congressman, Jim McDermott, involved, I got the ambassador to Slovenia involved, I got the FBI involved and I finally got it returned with a written apology.”

Where the U.S. government failed, a toilet factory prevailed in bending Krafft’s will. When, in 1999, he was invited to work for two months as an artist-in-residence at Wisconsin’s Kohler Company, world’s largest manufacturer of porcelain plumbing fixtures, Krafft planned to use the opportunity to continue work on the ceramic weapons. But it was shortly after the Columbine massacre and the company was adamant in nixing Krafft’s plans. “So, I was stuck for another object to turn into porcelain.”

Undaunted, he visited the nearby town of Sheboygan Falls. “I went into a dime store and they had old, obsolete skateboards on sale. And I thought, ‘That’s an interesting thing and it’ll be a good surface to paint a picture on — I’ll just make porcelain skateboards.”

Again, as with the guns, Krafft slip-cast the skateboards and precisely reproduced them. “Everything’s porcelain,” he tells me. “Even the trucks.” In an article Krafft wrote about the project for Juxtapoz magazine he says, “The truck mold is an engineering feat in itself that took me two weeks and two tries to get right. It’s six pieces. The decks would often break from the kiln car vibrations — the cars banged each other as they were pushed into place by forklifts. If that didn’t do it, the heat and shrinkage tore them apart in the kiln.”

One of the best and goofiest of the bunch features a portrait of Martha Stewart — in the classic Delft blue. For the board’s underside Krafft made an elaborate “M.S.” monogram that resembles one of those old, gorgeously tangled ones that the nobility used to have on the doors of their carriages.

“You oughta get Martha to buy that one,” I say.

“I tried,” Krafft says, “but I never heard from her.”

The international attention Krafft’s work has attracted hasn’t yet translated into anything approximating middle-class income. He still lives an artist’s life in the Northwest, watching every dollar, dining on 99 cent tacos at Mexican groceries, sharing his rented ramshackle house with a roommate. He does sell his work occasionally — the top price is in the $2,000 range, with smaller pieces going for considerably less — but he’s not likely to reach Thomas Kinkade’s level of market penetration anytime soon.

One of his most broadly marketable ideas may be Spone, a name he’s trademarked, his own twist on traditional bone china. Bone china — porcelain with milled cow bone mixed into it — has been around since Josiah Spode II invented it in the 18th century. Krafft’s Spone, however, uses human bones. As he explained to Mortuary Management magazine, “Human bone china has been made before by artists for each other, but I want to create an elegant and totally unique memento mori for anyone who wants one.”

Krafft’s first Spone project was done for the wife of a friend. When the friend, who had been a devotee of the Indian guru Rajneesh, died and was cremated, the man’s wife asked Krafft to make something with the ashes. Krafft created two polychrome painted statues of Ganesh, the elephant-headed god of Hindu legend. He gave one to the widow and kept the other.

The edginess of Krafft’s art has become more prickly as he has moved into themes that are pointedly sociopolitical. He likes theater, to stir things up, and work such as the Disasterware and the Porcelain War Museum (“Been there, smashed that” is the museum’s motto) is doing just that.

Consider his pieces that evoke Germany under the Nazis — the Adolf Hitler teapot, for instance, with two Disneyesque bunnies perched on either side of it; or the tiles depicting a Nazi rally; or his nonceramic series, which uses photos printed on velvet and a Czech crystal bottle etched with a swastika in a biting spoof of one of those gauzy ad campaigns for perfume that are ubiquitous in magazines like Vogue, Elle and Harper’s Bazaar.

The idea for the faux perfume campaign, Krafft tells me over dinner, came to him when he was in Sarajevo with NSK. While looking at the bombed-out former Olympic village, collective member Peter Mlakar said, “Ah, the smell of blood and snow. If I could bottle that scent I’d create a new fragrance for the 21st century and call it ‘Forgiveness,'” which is the name Krafft has given his specious scent.

“Yes, I’ve had people get angry about my work,” he says. “Some woman called me out because she thought I was making light of the occupation of Holland during World War II. She said, ‘Don’t you know how the Dutch suffered during World War II. Why are you making fun of that? What would possess you to mock their suffering?’ And I said, ‘I’m not mocking the suffering of the Dutch. It’s a purely decorative dialogue on defense and destruction.'”

Krafft’s fascination with totalitarianism and its trappings is one of those risky odysseys that artists sometimes make so that the rest of us can safely view the results of their intellectual inquiries under the illumination of track lighting in a clean white gallery. He’s especially curious about the horrific political transformation that occurred in Europe in the 1930s and ’40s, an era that is a regular preoccupation in his more recent work.

As we discuss it, he seems genuinely perplexed that intelligent people could subscribe to a far-right ideology such as that which swept through Germany in the years before and during World War II.

“Why was Ezra Pound a fascist?” Krafft asks. “Here was one of the greatest poets of the 20th century. Why was he involved in this business? Here’s a very intelligent guy who knew everybody there was to know and he’s completely behind Mussolini. And when they release him from the asylum he’s unrepentant.

“I’m deeply into exploring the other point of view in a certain time period, the ’30s and ’40s,” Krafft continues. “I lose patience with the right wing in America right now. I just think that they’re dunderheads. I’ve become a connoisseur of this kind of propaganda, but it has to be from a certain period — I can’t stomach Rush Limbaugh.”

To hear Krafft get going on this subject is like taking a guided tour of his brain’s engine room — down we go into the place that powers him, that keeps him dauntingly prolific. He’s very candid and doesn’t hesitate to expose his own thought process, even where it’s unresolved. Like many artists, he employs his work as a probe, a device, which he uses to explore the things he’s curious about, the ideas he’s grappling with. What results is a reflection in the form of an intellectual biography that he illustrates as he moves through his life, partly to understand, partly to amuse himself and others.

“You see, I don’t have anything to believe in myself, really,” he says, “and I’m wondering how another person comes into a belief system and becomes utterly convinced — it becomes theirs, it defines their personality, it defines their history as a human being.

“I’ve gone to India three times looking for gurus, I’ve read varieties of books about people who have supposedly gotten closer to God than other people have, and saints fascinated me for the longest time,” he continues. “Drifting into the realm of politics, how does somebody come to believe in a political system and embrace it and work for it and even sacrifice their lives for it, be committed to die for it?”

Krafft says he is curious about the fervor of believers, but not jealous of their direction and devotion. “I think I’m happy not to believe in anything,” he says. “I have to be. Why be miserable about it? That’s a waste of time. I really enjoy finding the logic to these belief systems, up to a point. And I envy it somehow. But I’m not looking for something to believe in, I’m looking for how others have come into belief. Their stories fascinate me.”