The experience of the immigrant in America is one of doubled displacement, of feeling torn between two identities and at home in neither one, and if you read much contemporary fiction you've probably seen so many variations on this theme that, unless you happen to belong to the immigrant group in question, it's hard to muster much enthusiasm for the latest iteration. But it would be a mistake to write off Gary Shteyngart's rambunctious new novel as one of those solemn tales of wistful dislocation.

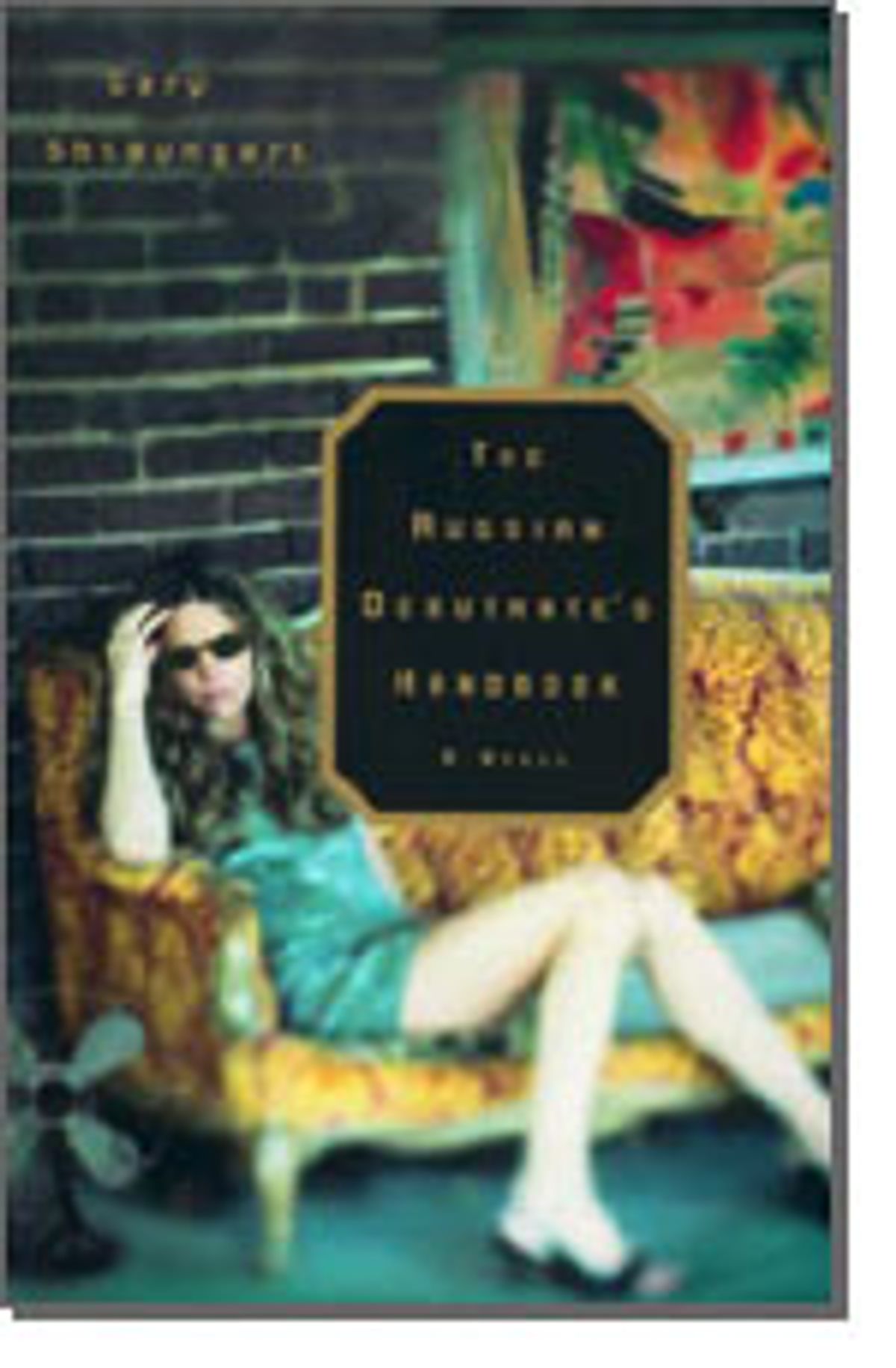

For one thing, the immigrant in question, one Vladimir Girshkin -- born in Leningrad and dragged kicking and screaming to the U.S. by his parents during the 1970s when "Jimmy Carter swapped tons of Midwestern grain for tons of Soviet Jews" -- hightails it to Eastern Europe early on in the book. So no moping around the Wal-Mart. For another, "The Russian Debutante's Handbook" is a blisteringly funny, almost frighteningly energetic novel of adventure, perfidy and even a car chase or two. So no New Yorkerish moments of quiet epiphany here, either. There's epiphany, all right, but Shteyngart, like his protagonist, is a Russian at heart, and nothing about Vladimir Girshkin, for all his sad-sack ways, is quiet.

Vladimir, who works for near-minimum wage at the Emma Lazarus Immigration Absorption Society, is the throwback in the Girshkin family, and the cause of endless lamentation for his parents. He still broods over the trauma of being called a "Stinky Russian Bear" at his American kindergarten and pines for the Motherland, or at least his childish recollection of it. His best friend tells him "you have the bearing of an emancipated serf." His mother, a successful CEO, is worried that the only thing her son's education at a "progressive Midwestern university" has suited him for is advising her on the most "sensitive" (i.e., non-actionable) way to sack her black marketing director. And as for Vladimir's physician father, among the first things we hear him say is "Medicare fraud is not really a crime."

Despite Vladimir's meek and melancholic propensities, the apple doesn't fall far from the tree. In a naive attempt to collect a little extra cash with which to impress his American girlfriend, he manages to offend a Catalan drug dealer and is forced to flee to Prava (Shteyngart's inexplicably coy pseudonym for Prague). There, he goes to work for a Russian gangster nicknamed the Groundhog, who sees great financial promise in Vladimir's ethnicity ("All you need is three Yids to rule the world").

Galvanized in some mysterious way by finding himself amid the ruins of his Soviet Eden, Vladimir launches a successful plan to bilk gullible Americans in a pyramid investment scheme comprising a chimerical "brand-new high-technology industrial park and convention centre," "modernized" Uzbek film studios and "a vocational school for the Yupik Eskimo in Siberia." There's also an actual nightspot dubbed the Metamorphosis Lounge, where intimate services and ample quantities of horse tranquilizer can purchased. Oh, and a literary magazine, too.

The literary magazine makes Vladimir a big shot in the cooler reaches of the American expat scene, and Shteyngart finds plenty of opportunity for satire in "white Middle Americans with a fashionable grudge." But it's the Russians, and the Stolovans (Czechs), who get the largest portion of his strangely loving yet merciless attention. In his eyes, they're incorrigible hustlers and cheats, operating on the principle that "The world owes us for the last 70 years." The Groundhog is both casually brutal and plaintive: "Why don't you ever spend time with your Russian brothers?" he asks Vladimir before authorizing the American to lead a Savonarolan purge of the operation's kitschiest trappings. Into a bonfire of the vanities go "the nylon tracksuits, the Rod Stewart compilations, the worn Romanian sneakers, everything that had qualified the Groundhog's vast crew as Easterners, Soviets, Cold War-losers."

At one point, Vladimir gets a call from a friend, a former Soviet apparatchik, looking to unload 300 ill-gotten Perry Ellis windbreakers. Vladimir in turn asks the older man, named Frantisek, for advice on how to handle the more troublesome elements in the Groundhog's ranks. Their conversation is worth quoting at length, since it captures the irresistible blend of the grandiose and the crass in Shteyngart's post-Soviet characters:

"'The Russians of this calibre [said the apparatchik], they only understand one thing: cruelty. Kindness is seen as a weakness; kindness is to be punished. Do you understand? You're not dealing with Petersburg academicians here or enlightened members of the fourth estate. These are the people that brought half this continent to her knees at one point. These are murderers and thieves. Now, tell me, how cruel can you be?'

'I have a lot of anger in store,' Valdimir confessed, 'but I'm not very good at expressing it. Today, however, I lashed out at the Groundhog, my boss --'

'Good, that's a good start,' Frantisek said. 'Ah, Vladimir, we are not so different, you and I. We are both men of taste in a tasteless world. Do you know how many compromises I have made in my life? Do you know the things I have done ... '

'Yes, I know,' Vladimir told the apparatchik. 'I do not judge you.'

'Likewise,' Frantisek said. 'Now remember: cruelty, anger, vindictiveness, humiliation. These are the four cornerstones of Soviet society. Master them and you will do well. Tell these people how much you despise them and they will build you statues and mausoleums.'

'Thank you,' Vladimir said. 'Thank you for the instruction. I will lash out at the Russians with my last strength, Frantisek.'

'My pleasure. Now, Vladimir ... Please tell me ... What the hell am I supposed to do with these goddamn windbreakers?'"

Will Vladimir's innate wimpiness or his newfound braggadocio win out? Will he choose the staid, clean, straight-arrow American side of himself, or succumb to his wild and wooly inner bear? Unlike the immigrants in more genteel literary fiction, he won't find this to be a subdued and poignant struggle. Before this dilemma is resolved, there will be tragic moments, yes, and violence, and, heaven knows, lots of exclamation points. These are Russians, after all.

Shares