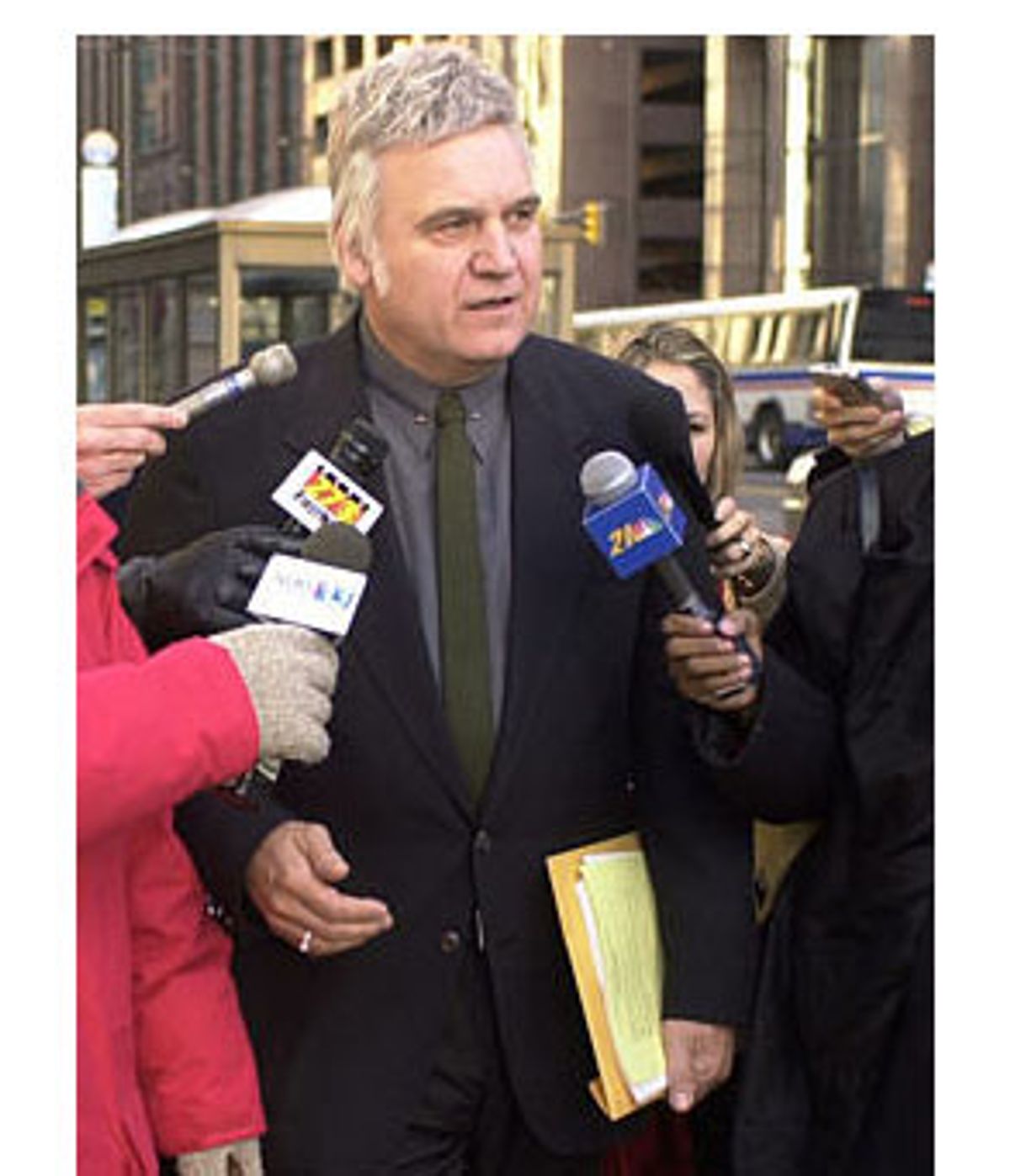

Congress' near-unanimous vote Tuesday night to expel nine-term Ohio congressman and convicted felon James Traficant was hardly a surprise to television viewers around the country who had glimpsed his bizarre defense against ethics charges in the past two weeks.

His references to "gastric emissions" and "Playboy bunnies" undoubtedly produced as many guffaws as his feral hairpiece and "Beam me up!" remarks on the floor of Congress regularly do. But the antics couldn't convince House colleagues to buy Traficant's argument that his recent federal conviction on bribery, corruption and racketeering charges was pure payback for his outspoken -- and at times outrageous -- views.

If Traficant's tale played as comedy to much of its national audience, the story takes on tragic overtones from the perspective of many in his northeastern Ohio district, where his fall from folk hero to felon mirrors Youngstown's calamitous descent from Steeltown U.S.A. to Crimetown U.S.A.

Traficant, only the second representative to be formally expelled from Congress since the Civil War, will be sentenced to up to seven years by a federal judge next week. But only the history of the once coal-rich Mahoning Valley and its fading fortunes can explain why some pundits predict that the Democrat-turned-Independent could net 20-some percent of the vote this fall for his old seat -- even if he runs from prison, as he has vowed to do.

During his 22 years in public office, he routinely garnered 70 percent or more of the local vote. His support is strongest among the over-50 population, according to Youngstown State University professor William Binning, chairman of the political science department. Not coincidentally, those are the same residents with the clearest memory of Youngstown's heyday as a steel-making giant.

While his stock has sunk since his indictment last year and conviction by a Cleveland jury in April, Traficant's maverick "up-yours" stance has long charmed Youngstowners whose falling out with the federal government began with the first steel mill closings in 1977, when the Carter administration refused to back a local plan for worker ownership of the plants.

"He represents a ... politics of resentment," notes YSU labor expert John Russo. "It's a resentment of the community for what happened to hard-working, salt-of-the-earth, good people who believed in the American dream."

A Youngstown native and high school football star, Traficant entered the political scene as sheriff in 1980. As 50,000 workers lost their jobs, unemployment reached 20 percent and the hardscrabble town became fed up with empty political promises, he cemented his position as a populist champion when he refused to foreclose on houses owned by laid-off steelworkers.

"I kind of feel a devotion to him," says Sandy Sayers, a law office clerk who grew up on the south side of Youngstown, where "black gold" once rested on every window sill and the sound of trains leaving the mills at night lulled residents to sleep. "He helped our community a lot. He's the only one that ever comes to fight for Youngstown when we have any problems," said Sayers, whose father and grandfather both worked in the mills. "I kind of feel that he's guilty of what he did, but show me one of them up there who aren't. I definitely think he was singled out."

It isn't the first time that Traficant's battles have become the community's. In 1983, when the government brought its first case against him, he became the first individual ever to beat federal racketeering charges without a lawyer: Despite taped evidence and a signed confession, he convinced a Cleveland jury that he had accepted a bribe only to carry out a one-man sting operation against local mobsters.

That defiance toward the U.S. Department of Justice only heightened his popularity, fueling his successful run for Congress a year later -- even as his mythic stature angered some in the business community. "He's personified and twisted the feeling that we've been left behind, that we've been victimized ... into a political culture that's incredibly self-destructive, and that's the tragedy," says Andrea Wood, publisher of the local Business Journal, who has covered Traficant since 1980, when she was a TV newscaster.

During his 18 years in Washington, he was noted for his disheveled suits and bell-bottoms, as well as his flippant one-minute speeches on the House floor. Often punctuated with the Star Trek catch phrase "Beam me up!," the statements, catalogued on his Web site, read like a mix of populist rhetoric and rap lyrics. In one such incantation in 1998, he riffed: "Does America now have two legal standards, one for you, one for me; one for he, one for she; one for generals, one for soldiers; one for presidents, one for residents?"

In the Mahoning Valley, encompassing Youngstown, the neighboring city of Warren and various suburbs, many residents realized that the 61-year-old ex-congressman often rode a slippery edge between renegade and jester. Indeed, in the early 1980s, local Democratic Party chairman Don Hanni tried to block Traficant's political ambitions by having a court declare him mentally ill -- a move that led Traficant to quip frequently that he was the only member of Congress whose sanity was court-certified. But locals remember him most for his pork-barrel politics and hometown loyalty.

"People are somewhat unique here, but they're not stone crazy, and if you're winning with a 70 percent margin, obviously there are a lot of people who in one way or another you've touched so that they feel you can do something positive for them," said local attorney Alan Kretzer, who was active in the Democratic Party when Traficant started his career.

Kretzer recalls Traficant ending a sidewalk conversation with him one day when an older woman "one step away from being a bag lady" asked to speak with him. "Most public officials would have said, 'You call my office,'" Kretzer says. "He's a demagogue, but he also ingratiates himself with normal, rank-and-file, poorer people. He probably shouldn't have ever been in Congress. But he's a masterful politician. He understood the mindset of the majority of his constituents."

He also brought high-profile federal projects to Youngstown, including an U.S. Army Reserve air base, two federal courthouses and $25 million for a convention center that has yet to be built.

"Even people at the Chamber of Commerce who can't stand the fact that he's brought such negative attention to the valley, even they will have to admit he did a pretty good job of bringing money to this valley," notes one-time Traficant supporter Scott Lewis, who runs a real estate firm started by his grandfather more than 50 years ago. "Whenever I would go see Traficant he was always good to me. When I would run into him, whether at a Rotary meeting or a wedding, he always remembered my name and my dad's name. He was very receptive to business interests."

Though Lewis said he never detected the slightest hint that the congressman expected illicit compensation, Traficant's receptivity apparently did cross the line with other business people. Indeed, the federal government's star witness against him was J.J. Cafaro, scion of one the area's most powerful families (second probably only to the DeBartolo clan, which also fell into disrepute nationally when 49ers owner "Eddie D" pled guilty to charges of bribery involving a Louisiana gambling venture).

Cafaro, who pled guilty to one count of conspiracy to bribe, testified that he provided Traficant with thousands of dollars of farm equipment and other items in exchange for meetings with top government officials in order to secure deals for his aerospace company. Former Traficant employees also testified that they were required to work on his farm or expected to give him kickbacks out of their government salaries.

Traficant's scheduled sentencing next week will cap a series of state and federal probes that netted convictions of more than 80 people in the Mahoning Valley, including judges, prosecutors, numerous local attorneys and the local sheriff. It also exposed Youngstown's criminal underbelly to a national audience. Feature stories highlighting the lawlessness in Youngstown carried headlines such as the New Republic's "The City That Fell in Love With the Mob" and U.S. News & World Report's "The Sopranos Come to Youngstown, Ohio."

According to the recent book "Steeltown U.S.A.: Work and Memory in Youngstown," by YSU's John Russo and his colleague Sherry Lee Linkon, the city had the nation's highest ratio of FBI agents per capita in the late 1990s. But the outlaw mentality had an honorable heritage: Russo and Linkon trace organized crime in Youngstown back to the 1920s, when citizens banded together to protect the interests of immigrants against the Ku Klux Klan. In ensuing years, an apathetic public allowed a degree of criminality to persist. And until the late 1970s, when the steel industry abandoned the area, legitimate business kept the area economically healthy and served as a counterweight to the mob.

"After the mills shut down, you had a more pronounced vacuum and they became the only game in town. The politicians had everything to gain and nothing to lose by playing ball with them," says Jim Callen, a local activist and director of Northeast Legal Services. "I think Jim has been characterized by some as a problem back here," said Callen, who led a delegation to Palermo, Italy, two years ago for a symposium on the role of civil society in countering organized crime. "I think he's been more of a symptom of a problem, just as organized crime has been a symptom of a problem. We've had a culture that has tolerated this corrupt behavior. We've had essentially a culture of lawlessness."

As industry departed, so did many of the city's residents: The 2000 census counted 82,000 residents in Youngstown, less than half the population of 40 years ago, though the suburbs, especially those to the south, have grown. The darkest days are over, but the local economy has yet to recover its earlier luster. In fact, during Traficant's ethics hearing, a bankruptcy court was liquidating the retail chain Phar-Mor, whose arrival on the scene in 1982 promised to lift Youngstown out of economic doldrums. Instead, Phar-Mor founder Michael Monus is still doing time for a 1995 conviction for fraud, tax evasion, and embezzlement. The Phar-Mor closing could cost the Mahoning Valley upwards of 800 jobs, according to Wood.

"As the national economy is imploding, we are imploding here," she says. "When you juxtapose that with the political implosion of Jim Traficant, the business community is staggering. It's the worst it's been since the steel shutdown. It's very difficult to divorce the political situation from the economic situation, because it's so bleak right now."

It is rife with irony that one of the industries the area has turned to for economic rescue is the prison industry. In the 1990s, four prisons were built in the area, though one of them has since closed. Traficant played a role in bringing some of those lockups to the area -- and was trying to bring in another to a brownfield where the old Youngstown Sheet & Tube plant once stood. Pundits speculate that he might have retired from Congress to a cushy job in the corrections industry had his federal convictions not steered him to prison in a less respectable fashion.

Like all tragic figures, Traficant was done in partly by his own hubris. First, he crossed party lines to support Republican Dennis Hastert for the speaker position. While that stunt secured a $25 million convention center deal for the area, it cost Traficant politically. The Democrats refused him a committee seat, and union officials who had long stood with him dropped their support.

Another high-wire act that Traficant will pay for was his decision to forego legal representation in his second federal trial this spring.

"Had he been represented, he would have probably won on some of the counts," says Kretzer. "It was a try-able case. Any lawyer who followed it would agree that he did an awful job. It was too complex a case for an individual layman to handle himself."

After losing the Democratic and union establishment, Traficant also suffered in public opinion after his conviction. But Binning, the YSU professor, says his support actually bounced up after last week's ethics hearing, when one of the defense witnesses testified that the feds were so eager to nab Traficant that they had tried to force him to provide false evidence against the congressman.

One juror has said that he wouldn't have voted to convict Traficant had that witness testified in court. That sentiment is winning favor in Youngstown among those who can't forget Traficant's defense of the area's steelworkers - and can't help wondering whether their hometown boy will do more time for his crimes than the Enron honchos and the accountants who aided them.

"He's not wanted up there [in Washington]," says Sayers. "Here comes Jim Traficant, with old suits and wigged-out hair getting mouthy. He upset the wrong people, and they went after him. If they want to take him down, they should look at everybody else up there. Without him, it doesn't seem like there's anybody who's going to care about a small community."

That he managed to win his last race in 2000, even after the federal investigation against him had become front-page news, is a sign of his ballot-box prowess. And while recent redistricting as well as Traficant's rightward tilt in the last two years will cut into his support, local experts -- including Youngstown Vindicator columnist Bertram de Souza and YSU's Russo -- are still predicting that Traficant will net 20 percent of the vote, or more, in the four-way race.

"The important thing to realize is he's not leaving," said Wood. "As long as he's drawing a breath, Jim Traficant will be making news in the Mahoning Valley."

Others, however, sense the passing of an era, and some of them can't help but be wistful.

One person who will miss him is Vindicator political reporter David Skolnick. "Traficant's a full-time beat at times," he says. "You never know what he's going to do, what he's going to say. He has never taken a phone call from me in my entire time covering him. He's completely inaccessible. You don't dare call him at home. You don't dare visit him at home.

"But it's a rare opportunity to cover someone that colorful and engaging. It makes being a reporter very interesting. Whoever replaces him, even if they're a superior congressman, it's not going to be the same. It's going to be back to boring stories about God-only-knows-what."

Shares