Photographer Flor Garduño says that seven out of 10 of the models she worked with on her new book, “Inner Light,” a collection of nudes and still lifes, have gotten pregnant.

“Among my friends,” Garduño tells poet Verónica Volkow, who wrote the introduction, “word started getting around — it was a joke — that if someone wanted to get pregnant, she had to pose for one of Flor Garduño’s photographs … one of the models got pregnant, even though she was using birth control.” Still another woman saw Garduño’s lush black-and-white images and “a short time later she also got pregnant,” the photographer says.

It’s hardly surprising. There is an unmistakable air of fecundity about Garduño’s work and it goes beyond matters of reproduction. Here are pictures with ideas attached — thinking, breathing, feeling photographs. Garduño’s strong, evocative symbolism and her poetic sensibility coupled with a flawless sense of composition make these sensuous, often ethereal images the sort of pictures you can look at over and over; these are photographs worthy of staring at, then closing your eyes and remembering. The funny thing is — given that many of the photos are nudes — when you do stare, you find that you’re not looking where you might expect to.

Making a nude photograph that possesses intellectual weight is a challenging proposition. A photograph — any photo — of a naked person is charged; nine out of 10 of us will have to look at it whether it’s any good or not. Men, who are ostensibly stimulated by visual images more than women are, find nude photos of females all but irresistible. Most photographers who shoot nudes know this, but fail to transcend it even when they try. Yet some, and Garduño is preeminent among them, make pictures that have so much going on that every element of the image integrates with every other and our eyes go wild, looking everywhere. These aren’t merely nudes, they’re novels or perhaps epic poems rendered by a magical realist.

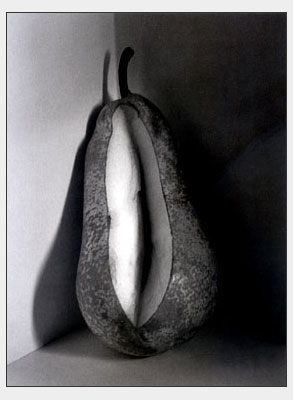

“Holistic” is a dreadfully overused word, but I can’t think of a better one to describe Garduño’s ability to capture not just the sensuality of a woman’s body, but also the sensuality inherent in an entire scene. Who knew that leaves could be sexy? For that matter, since when are pears erotic? Well, since Garduño sliced a wedge from one and propped it against a wall. And don’t get me started on the pomegranate, the one with the seeds wantonly spilling out.

But most of her images — nudes or not — aren’t even specifically about sex. They’re about life and nature and procreation and form and death and funniness and beauty and dreams and whimsy and I take it back — they are about sex. Life, when it’s really full like that — fertile with ideas and emotions, electric with thought and fantasy — is the very quintessence of sex. Good sex, the real thing, cannot be separated from every other aspect of life. That’s why photography that is only about sex is often sexless and boring.

Garduño’s work is in major collections around the world, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. Her earlier book, the critically acclaimed “Witnesses of Time,” is a visual meditation on the sacred and symbolic as reflected in the everyday lives of native Indians in Mexico, Guatemala, Peru, Bolivia and Ecuador who still practice ancient rituals. And, though “Inner Light” is utterly different thematically, you see the ripple effect “Witnesses of Time” has had on some of the images in this book; Garduño is well attuned to the intersection of spirit and matter; the power of the iconic object and how objects become iconic when presented as the keystone in a spiritual story, a narrative we seem to be witnessing as we view her photographs.

Garduño lives in Switzerland and Mexico (her Swiss husband, Adriano Heitman, is also a photographer) and has two children, one of whom, Azul, appears in some of the pictures in “Inner Light.” The photographer seems to have a philosophical kinship with the legendary Manuel Alvarez Bravo, which isn’t surprising: Like Bravo, a native of Mexico, Garduño began her career as his assistant. Some of her photographs even appear to make playful tribute to his, such as “La Nopala,” a seated nude woman looking at the viewer through eye holes cut out below an array of buds on a piece of cactus. “La Nopala” humorously echoes Bravo’s famous “La Buena Fama Durmiendo” (“Good Reputation Sleeping”), a solemn image of a nearly nude woman lying next to four prickly cactus buds. And one of Garduño’s most sensuous images (and most exquisite compositions), “Vestido Elegante” (“Elegant Dress”), a nude female partly visible behind large, swordlike leaves, is vaguely reminiscent of Bravo’s “Fruta Prohibida” (“Forbidden Fruit”), a view of a woman, her shirt open, her breast visible behind long blades of grass.

Garduño, however, though she is clearly influenced by Bravo, possesses her own very distinctive vision and is a gifted picture maker in her own right. For one thing, she’s more prone to frolic than Bravo. Her 1998 photograph “Pez Espada” (“Swordfish”), a nude holding a massive swordfish head on top of her own, is certainly surreal, but it’s also a hoot and something of a challenge. The fish’s giant eye stares out at the camera lens, looks right back at the viewer, and the head dwarfs the woman holding it. It takes a few moments before you even notice that she’s nude. Then you realize that the pose is similar to Rodin’s thinker and it becomes clear that Garduño’s sense of humor sets her work far apart from Bravo’s often (though not always) somber imagery.

But Garduño can be contemplative, too. One of the most exalted nudes in the book is her “Vestido Eterno” (“Eternal Dress”), a madonna-like picture of a young woman, her eyes closed, her head turned slightly upward and a garland of white roses draped across the top of her breasts. It’s a picture you could hang on a wall and never tire of, it is so rich with references to religion, mythology and eroticism. The woman’s subtle expression, suffused with emotion, is simply compelling and seems to change as you gaze at it. If art is the transmission of feeling then Garduño has made a masterwork with “Vestido Eterno.”

What comes through vividly in her photographs is that this is the work of a happy person, which is unfortunately rare in art today. That Garduño has managed to imbue the work with that feeling is testament to her inner resourcefulness, her toughness and vulnerability. There is plenty to be sorrowful about these days, but she’s managed to capture those eternal qualities of nature and humanity that conquer that sorrow. In the introduction, Volkow writes, “Garduño looks at the world with the eyes of a treasure’s caretaker, which are the same as those of a pregnant woman. Every figure glows as if it were fervently embracing a promise, beaming with an overwhelming fullness. Each fruit, each body is like a star: It radiates a beauty that emerges from an overflowing richness. Every form seems to express an innate force; it dawns with the power of its strength. Garduño shares with us a woman’s complicity with the vital force of objects and bodies. Everything here lives from within the miracle of fecundity.”

To which one can only respond: Yes! And thank god for poets — both the ones who use words and those who use cameras.