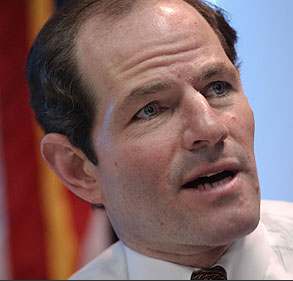

Eliot Spitzer spent two years working on mergers and acquisitions for a white-shoe corporate law firm. He borrowed millions of dollars from J.P. Morgan to finance his successful 1998 campaign to be New York’s attorney general. He lives in a Fifth Avenue apartment worthy of Gordon Gekko. He’s even claimed that all his friends are either investment bankers or the lawyers who represent them.

But these gilded connections haven’t kept the born-and-bred New Yorker from ripping into the nation’s financial giants like an armor-piercing bullet. While Congress and the SEC’s Harvey Pitt dither in the face of widespread corporate malfeasance, Spitzer is a busy man. You could call him the nation’s toughest corporate cop. He’s certainly the most feared man on Wall Street.

Spitzer’s crusade first attracted public attention in April, when the Princeton- and Harvard-educated prosecutor announced that his investigation into analysts’ stock-buying recommendations had turned up a smoking gun. E-mails from within the investment banking firm Merrill Lynch proved that analysts privately slammed stocks that they were publicly praising. Their behavior reflected a classic conflict of interest. Merrill Lynch was afraid to antagonize clients who were filling its coffers with millions of dollars of investment banking fees.

Merrill Lynch never admitted guilt, but in May the firm settled for $100 million and agreed to change the way its analysts did business. Other firms soon followed suit. The attorney general’s office continues to pursue several investment houses for additional conflict-of-interest violations, and on Sept. 30 Spitzer upped the ante. His office sued the former top officials of five telecommunications companies, arguing that they gave investment banking business to Citigroup in exchange for shares of hot IPO companies, which they would then “spin,” or sell immediately, for windfall profits.

Will Spitzer’s high-profile crusade result in long-term change? Some critics argue that Spitzer, rumored to be angling for the 2006 New York governor’s race, cares more for publicity than anything else. No Chinese wall separating research from investment banking has been established as a result of Spitzer’s actions, and Merrill’s seemingly large settlement amounts to but a fraction of its annual revenue.

Spitzer has also given up his lone-wolf ways, agreeing on Oct. 3 to work with the Securities and Exchange Commission and the National Association of Securities Dealers on a “swift and appropriate resolution” to Wall Street’s ethical lapses. But is working hand-in-hand with Harvey Pitt’s industry-friendly SEC the best way to wage war on Wall Street?

Salon asked Spitzer about reforming Wall Street, his role and his office’s plans for the future.

You’ve recently launched a series of lawsuits that aim at the practice of giving hot IPO shares to CEOs. How do these cases fit into your previous focus on bogus recommendations by analysts?

The issues are interrelated to the extent that part of the larger structure there had to do with analysts pumping stocks for investment banking business coming in, and as part of the structure, the CEOs of the companies that brought the business in did indeed receive the hot stock allocations.

Until recently, you were working alone. Why did you decide to join forces with the SEC and other federal regulators?

I don’t think anybody would dispute that it is better policy if we can all work together, whether it be the stock exchange, the NASD, my office or the SEC. I think we all understand that there is an obligation to try to bring some uniformity and regularity of practice to this area. So whatever substantive disagreements there may be, we have to make a serious effort to work those through and come up with a common set of standards.

But you’ve complained about the [SEC’s] lack of action in the past. Are you convinced that they’ve turned over a new leaf?

First, I think they’re acting, at this point, aggressively. I’m not going to get into the business of taking back anything I said before; I wouldn’t do that. I think those were appropriate comments at the time. But I think there are also different phases in this process. The first phase was to frame the problems through investigations, demonstrate the magnitude of the problem. Then there comes a moment when you have to try to resolve it; and trying to resolve this issue can’t be done unilaterally, while making cases can be … The natural evolution of this was that there was going to be a moment when the parties had to come together.

The $100 million settlement with Merrill has struck some critics as a great deal for Merrill, particularly in light of their proximity to Enron. Why did you settle instead of pursuing the case and maybe putting some people in jail?

Everything in due course. We’re now looking at the Merrill settlement from the vantage point of October. On April 8, when I raised the issues on Merrill and provided the proof, everyone said, that can’t be true, that’s wild. The point of the Merrill settlement was to begin the process of structural change. The $100 million in your statement is correct. It’s objectively a large sum of money, but it’s not a large sum of money to Merrill. But the structural change that we initiated with Merrill was the important point. Breaking the logjam in the debate about the relationship between analysts and investment bankers was more important than exacting an extra pound of flesh.

Are you looking only at Wall Street, or is the scope of a possible solution broad enough to include all public companies or investment houses?

The entities we’re dealing with in an effort to figure out how to restructure some of these problems are primarily the largest investment banking houses. That doesn’t mean that the solution won’t have a direct impact if regulations are promulgated on all investment banking houses, large or small. But certainly the entities that have been most involved, because we’ve been taking a look at their practices and because they’ve been working with us to come up with solutions, have been the largest investment banking houses.

What about finding a way to make executives pay? Is this going to happen?

Absolutely. That’s why we filed the case last week. It is an effort to disgorge from the CEOs their ill-gotten gains. I think it’s an important part of it. Not only is it a matter of simple equity, but also in terms of deterrence and the way people act down the road. There will be both civil litigation designed to get disgorgement and some of these guys are going to jail. There’s no question about it.

I’m tempted to ask who but I suppose you won’t tell me …

We could create our own little marketplace with bidding on who will end up rooming with whom, but I don’t think I should get into that.

What about market forces? In July, several pension funds called on brokerage firms to follow your conflict-of-interest rules. Is this the kind of reaction you were hoping for, and could this kind of market solution be enough?

Richard Moore [the sole trustee of the North Carolina Public Employees Retirement System] called and asked me if I would help him do that. In fact, I was on the phone with Richard this morning, because as the rules go beyond the Merrill settlement, the question is what he should do to best keep the pension-fund pressure on the [investment] houses. This is getting equity involved, which is critical whether it’s the pension funds or the other institutional shareholders — it’s their money. That’s not regulation; it’s just equity flexing its muscle, saying, We have a role. Hopefully that will be the long-term and important check, more than anything government does.

But I don’t think the institutions alone are likely to effect the changes we need. They’re certainly part of the answer. If we in government do what we can do and should do, and move with some alacrity, then I think the shareholders can move in thereafter and continue to apply pressure.

When I spoke to Joseph Stiglitz, author of “Globalization and Its Discontents,” he argued that the root of all the corporate malfeasance arrived in the mid-’90s with the rise of stock options as a means of compensation. He argued that it provided too much incentive for short-term measures designed to boost stock prices at the expense of long-term corporate health. Would you agree with that?

I won’t disagree with Joe Stiglitz, one of the brighter guys anyone could encounter. I think [compensation in the form of stock options] was one of the causative factors that led to what I call “the imperial CEO” who ran roughshod over traditional limitations on corporate governance. But I don’t think it was the only cause. There was a more generic breakdown in corporate governance. Boards failed to participate, audit committees failed to ask probing questions. Auditors became clients of the CEO, who tried to portray everything in the most favorable light rather than remaining true to the objective of transparency, simplicity and clarity. Institutional shareholders became even more passive than they had been traditionally and that meant that that check on the CEO disappeared. And then the investment houses, who were traditionally one of the marketplace checks on corporate behavior, were seduced into this unholy alliance with the CEO. So I think you had a breakdown all across the chain of corporate governance.

At what point did you decide to get involved, and why? After all, financial cases are typically started by the SEC.

We have bureaus that have done all sorts of interesting cases and not interesting cases — but the jurisdiction is enormous. It’s everything from civil rights to antitrust to consumer, healthcare, Internet, etc. Securities regulation is one of them. And as I do routinely, I sat down with the bureau chiefs and asked, What can we do that’s going to be more useful? Where can we use our jurisdiction to have a significant impact on protecting investors or workers or whoever it may be? And this was an issue that had been out there for a while. Journalists had been out there covering it, writing about it, but not much had been done from a governmental perspective. So we said, maybe we can do something here.

Your critics say that you’re bringing these cases to draw attention for a run for governor in 2006.

Look, you can’t stop people from speculating about what my motives might be. I can’t stop them, but they’re wrong, and as long as they can’t fault either the facts or the theory of what we’re doing, then I’ll just leave it to others to speculate as to why I’m doing what I’m doing. They’re wrong, but what more can I say?

What you’re doing with these Wall Street cases and other cases you’ve brought against Midwest polluters and gun manufacturers has been described as attorney-general activism. You’ve argued in the past that this trend is an attempt to fill in gaps left through deregulation, but do you ever worry, for instance, that you’ve opened up a Pandora’s box in which any A.G. with an agenda can make life miserable for those he disagrees with? What if a conservative A.G. starts suing abortion providers?

You’re mixing issues. Multiple layers of prosecutorial authority does not mean that the law can be or should be inconsistent. But multiple layers of regulatory authority — which can enforce existing laws — is something we have always had. That doesn’t mean that state law can be inconsistent with federal law. Of course it can’t be. It can be more demanding in certain cases but not inconsistent. But what we certainly have is the capacity for state, local and federal authorities to all prosecute the same theories. Look at the BCCI case, which is perhaps the largest bank-fraud case in history. [Robert] Morgenthau, the Manhattan district attorney, brought that because federal officials walked away from their obligation. They didn’t want to do it. So this is the structure we’ve always had and it’s served the public very well.

How do you see this playing out? Ten years from now, what will American business look like?

I think Wall Street will not only come back, it will be stronger because there will be a better ethical foundation to some of what had been wrong. That doesn’t mean there won’t be different problems of a different sort. Every 10 or 15 years, there has been a different sort of problem that emerges. It’s not because Wall Street is any better or any worse; it’s just the nature of these relationships and how they work over time. Different problems emerge that have to be dealt with.

And what about you? Where do you hope to be in 10 years?

Working on my backhand.