The nomination of William Pryor to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit should teach liberals once and for all never to underestimate George W. Bush’s chutzpah. Just when it seemed the president couldn’t possibly find any potential judges more right-wing than those he’s already appointed, he outdid himself. “It’s an extraordinary public record,” Ralph Neas, president of the civil liberties watchdog group People for the American Way, says of Pryor. “Rarely do you see someone so bad on so many issues at a relatively young age.”

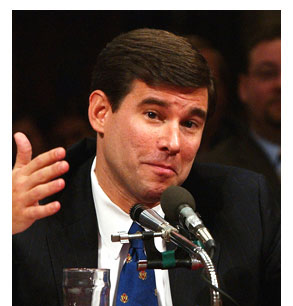

Pryor, the 40-year-old attorney general of Alabama, holds far-right positions on women’s rights, abortion, gay rights, the environment, criminal justice and the separation of church and state. Speaking at Pryor’s hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee yesterday, Sen. Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., said, “In a way, his views are an unfortunate stitching together of the worst parts of the most troubling judges we’ve seen thus far.”

Because Bush nominated him on April 9, two and a half weeks into the war with Iraq, Pryor initially didn’t receive as much scrutiny as judges like Priscilla Owen and Charles Pickering, both of whom the president renominated after a Democratic Senate rejected them. (Pickering is still awaiting a second hearing, while Owen is being filibustered by Senate Democrats).

Yet Pryor’s rhetoric over the years is at least as extreme as that of former Senate Majority leader Trent Lott, R-Miss., who stepped down in December after he was criticized for comments widely deemed racist, and Sen. Rick Santorum, R-Pa., whose anti-gay remarks in April created an uproar. And if his nomination succeeds, he’ll have a lifetime spot on one of the 12 courts that make up the second-highest judicial authority in America.

Pryor calls Roe vs. Wade “the worst abomination of constitutional law in our history” — meaning, Schumer noted, that he considers it worse than such dark moments in U.S. judicial history as Plessy vs. Ferguson, the 1896 decision legitimizing segregation, or Dred Scott, the 1857 decision affirming that slaves were property.

Pryor also believes that states have the rights to criminalize gay sex. Pryor echoed Santorum’s recent anti-gay remarks in a brief submitted to the Supreme Court on behalf of a Texas anti-sodomy statute in the Lawrence vs. Texas case.

The Texas statute, he wrote, is not discriminatory because it doesn’t make it illegal to be gay. “Rather,” he wrote, “the Texas anti-sodomy statute criminalizes petitioners’ sexual activity, which is indisputably a matter of choice. Petitioners’ protestations to the contrary notwithstanding, a constitutional right that protects ‘the choice of one’s partner’ and ‘whether and how to connect sexually’ must logically extend to activities like prostitution, adultery, necrophilia, bestiality, possession of child pornography and even incest and pedophilia (if the child should credibly claim to be ‘willing’).”

A fervent Christian and dedicated opponent of what he has referred to as the “so-called separation of church and state,” Pryor told an audience at a 1997 rally in favor of displaying the Ten Commandments in the Alabama Supreme Court building, “God has chosen, through his son Jesus Christ, this time and this place for all Christians … to save our country and save our courts.”

Judith Schaeffer, People for the American Way’s deputy legal director, says that what’s most disturbing about Pryor is his judicial philosophy, which puts states’ rights ahead of the Bill of Rights. He has consistently argued that civil liberties issues should be decided by majority vote rather than recourse to the Constitution. “One of the tasks of the next century will be to restore lawmaking and policymaking to the democratic process, not the legal process,” he said at a 1999 commencement speech.

Indeed, in Lawrence vs. Texas, he argued that the court erred in even agreeing to hear the case, since the “proper loci” for such issues are “the legislatures of the 50 States.” “Accepting petitioners’ invitation will take this Court perilously down the path toward permanently ensconcing itself as the final arbiter of the kulturkampf that is currently being waged over such sensitive and divisive social issues as abortion, sexual freedom, gender identity, the definition of the family, adoption of children, euthanasia, stem cell research, human cloning, and so forth,” he wrote. “If Roe v. Wade and its progeny have taught one lesson, it is that judicial attempts to resolve social disputes of this nature do not have a calming and stabilizing effect on our society.”

“His view is that the Constitution does not apply to certain issues pertaining to individual rights and liberties, such as school prayer and gay rights,” Schaeffer says. “He gave an example at his hearing — he said that the Supreme Court should not be able to tell Alabama whether or not it can carry out death sentences by using the electric chair. He said the court should not be able to say that using the electric chair constitutes cruel and unusual punishment.” Such logic, she says, “stands the Constitution directly on its head.”

There is, however, one case in which Pryor sided with the Supreme Court against states’ rights. He was the only state attorney general in America to file an amicus brief supporting the Supreme Court’s intervention in Bush vs. Gore.

“Pryor is nothing but a right-wing Republican activist who wants to get on the bench,” says Jamin Raskin, a professor of constitutional law at American University. “He reads the law completely through the prism of his political preferences and biases.”

As grim a farce as the Pryor nomination is, liberals can take comfort in the possibility that he’ll never actually ascend to the bench. “I certainly feel comfortable saying I believe the Senate will reject this nomination,” says Neas. Adds Raskin, “Up until this point, not a single Republican senator has voted against a single nominee to the federal circuit bench. But if senators like [Arlen] Specter or [Olympia] Snowe can’t vote against Pryor, then they really have become robotic partisans.”

If no Republican moderates prove willing to defect from the party line, Democrats may filibuster the nomination, just as they have with Owen and Miguel Estrada.

Yet even if Bush doesn’t get Pryor on the bench, his nomination, like so many other Bush policies, will likely have the effect of pushing the definition of “mainstream” even further to the right.

“In the big picture, I think the Bush administration is trying to shift everything judicial so far to the right that any Supreme Court nominee they come up with is going to look like a centrist,” says Raskin.

“One is left speechless at the people they’re bringing forward,” he continues. “Things have gotten way, way out of whack.”