Salvatore Bulamuzi lost five children in Bunia while the United States was liberating Iraq, and it did not make the news. He lost his parents as well — all killed in the Congolese war, where tribal militias fight for land rich in timber and diamonds, and Dantesque horrors of macheted infants, murderous 14-year-olds and HIV-laced rapes are so common as to be unremarkable.

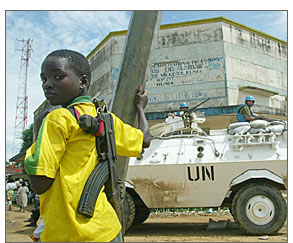

In that context, Bulamuzi’s story is not remarkable, either. News reports and interviews with those who live in the Congo or have recently left suggest that he is but one person adrift on a sea of madness. In the eastern part of Congo there is a town run by children, an uncontrollable army playing soldiers with Kalashnikovs. In the city of Bunia, men machete men, and underground there are diamonds and bones. At night the women hide in the forest because it is safer than in their homes, but they desperately hush their infants lest the noise bring looters who rape and sometimes kill.

“I am convinced now … that the lives of Congolese people no longer mean anything to anybody,” Bulamuzi told an Amnesty International representative at the start of the Iraqi war.

As harsh as the assessment seems, any evaluation of U.S. foreign policy or United Nations policy in the Democratic Republic of Congo suggests that he is right. The statistics of the war there are staggering: More than 3.3 million lives lost in five years, and more civilian deaths in one week than in the Iraqi war to date, according to research conducted by the International Rescue Committee included in a recent report issued by Watchlist, an international coalition of nongovernmental organizations focused on children in armed conflict. It is the deadliest conflict since World War II, and although a South African peace plan has been discussed, few are optimistic it will work.

“We believe that human suffering in Africa creates moral responsibilities for people everywhere,” President Bush said in a speech last week. But while the U.S. fights the war on terror, it has been 9/11 there for years — and few seem to care. On a five-day trip beginning Monday, Bush travels to five countries — Senegal, South Africa, Botswana, Uganda and Nigeria — to focus on HIV/AIDS, democracy, security and trade. But despite his stated concern for human suffering in Africa, he will not be going to the Congo.

In a series of interviews, experts on U.S. Africa policy suggested many reasons for this apparent oversight. Some see the crisis as so nearly impossible to solve that it would be political quicksand for Bush. In part because there is so little news coverage of the region, there is little public awareness, and so little public pressure for Bush to act. Others suggest that it represents Western racism, or the enormous cultural distance between Washington and the tropical forests of Central Africa.

Certainly these are not new phenomena. This is a place “of massacres, of blessings,” Joseph Conrad wrote of the Belgian Congo in “Heart of Darkness.” Later in that masterpiece, there was a more visceral description: “The horror, the horror!” One hundred and one years later, we are all part Kurtz. In a land cursed with an abundance of gold, diamonds and the minerals used in the high-tech industry, we are mystified by the chaos and repelled by it, even as we reap enormous economic benefits from it.

“The world is looting the dead body of the Congo,” says Didier Gondola, who was born in the country and is the author of “The History of Congo.”

On paper, at least, the U.S. government is concerned. According to the USAID Web site, U.S. national interests in the Congo are: “promotion of a democratic transition and sustainable economic growth in a country key to the stability and prosperity of all of central Africa; conflict reduction in a country where warfare still destabilizes vast regions and leads to a humanitarian emergency affecting millions of Congolese; and amelioration of health and environmental issues of significance to the Congolese, the United States, and the global community.” But total U.S. humanitarian aid to the Congo has been slashed by over a third, from $98 million in budget year 2001 to $62 million in budget year 2002.

“[The Bush administration] has been clear that they’re not going to concern themselves past a point with conflicts that don’t threaten us,” says Philip Gourevitch, author of “We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will be Killed With Our Families,” a haunting account of the 1994 Rwanda genocide. “In the case of Iraq, when they [the Bush administration] want to get involved they amplify the threat, but in a case like Congo, they’ll point to the lack of threat to justify non-involvement.”

Even among many human rights experts, there is a striking lack of outrage — but for far different reasons. Gondola says that he has passed through that state and come out on the other side of it: resignation. “I am beyond outrage,” he explains. “When you’re beyond that, you get a little bit calmer, and you look at things without your heart. If I were to be more involved, I could have a heart attack.”

The history of the Congo — richer in mineral resources than any other country in Africa — is one of bloody exploitation. Gold, diamonds, rubber and ivory have flowed to Europe and the Americas for a century from the area known first as the Belgian Congo, then as Zaire, under the West-backed regime of Mobutu Sese Seko from 1965 to 1997. The present conflict started in 1998, after Laurent Kabila took power, renaming the country again as the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Rwandan and Ugandan-backed forces have been trying to overthrow the government and control the resources ever since, in a wave of violence that resulted in the assassination of Kabila in January 2001 and the ascension of his son, Joseph. Today, the Congo is essentially split in half — with Kabila’s government ruling the areas around the western town of Kinshasa, and Ugandan- and Rwandan-backed militias fighting in the Eastern area of Ituri.

Uganda and Rwanda are but two actors in the six-year war an International Rescue Committee report describes as involving “seven nations, three main rebel groups and numerous militias fight[ing] over a complex mix of economic, ethnic, state and factional interests.”

The situation is so fluid and complex that it can be easy to despair of even understanding all the issues involved, let alone addressing them. There is the conflict in Bunia between the Lendu tribe and the wealthier Hemas, so reminiscent of the Tutsi-Hutu genocide. There is the clash between the government in Kinshasa and militias in the east. And there is the war fought by children; those who are not shot or hacked to death often die in the forest of malnutrition or malaria. The forests are sown with their bones.

It is easier to turn away, and that’s what we have done.

In the Congo, diamond fields represent such wealth that they are fought over and died for and the current violence in Ituri is largely their doing. Uganda, whose HIV program Bush will be lauding on his upcoming trip, remains one of the biggest buyers of the diamonds that fuel the ongoing conflict in the Congo. Ugandan forces, which took over the mineral-rich area of Ituri in 1998, officially left the country in May as the main condition of a December 2002 peace plan put together by neighboring countries — but the power vacuum left in their wake only produced the latest explosion of massacres by local tribal militias in Bunia, and Ugandan proxy warriors remain. Macheted infants and the rape of young girls are commonplace. Though the United Nations sent a small team of Uruguayan peacekeepers to the area in April to facilitate the Ugandan pullout, the results have been dismal. The violence has slowed since the arrival of 1,400 French troops in June but children continue to die of war-induced malnutrition.

Arrangements have been made for a transitional, multi-party government to be formed, but experts predict this, too, will end in disaster. “Split the government into factions?” says Gondola, a professor of African history at Indiana University. “This is really going to create a monster. It will just give the rebels official power.” Adds Gourevitch: “To a large extent the problem in Congo is a result of these African neighbors, so the whole ‘African-solutions-to-African-problems’ thing is more like substituting one African problem for another.”

According to Abdul K. Bangura, a Sierra Leonean professor of international relations at American University in Washington, Bush is unlikely to press Uganda on his trip to work toward a peaceful solution. “We have a very strong ally in President [Yoweri] Museveni of Uganda, and we need his support — especially now that we’re fighting terrorism in East Africa,” he says. He also believes Rwanda, another ally, is equally unlikely to be pressured by the Bush administration — even though an estimated third of the Congolese military are believed to be Rwandan soldiers who switched uniforms. Many Africans are questioning the double standards of U.S. foreign policy. “Here we have our own ‘boys’ doing the worst things in the Congo and we pretty much turn a blind eye, but we have no problem beating up on [dictator Robert] Mugabe and talking about regime change in Zimbabwe.”

If the U.S. does not become involved in the humanitarian crisis in the Congo, it’s because it’s in its national interest to leave the Congo in the fractured state it is — no matter how vast the slaughter that ensues. Although “conflict diamonds” — so named because they are gained cheaply through wars in the Congo and elsewhere — have gained the attention of the American public, the more widely used minerals smuggled out have not.

Coltan, a combination of minerals found in abundance in the Congo, is regularly used in the making of cellphones and laptops and can sell for up to $100 a pound — ten times what the Congolese who dig it up are paid. But as yet there is no public outrage over “conflict coltan,” and Gondola blames the news media and Microsoft for the lack of attention paid. “If there were a democratic government in the Congo, if the country owned all the resources, the price would go up,” he says. “Microsoft doesn’t want that, Bush doesn’t want that. So nothing will change. The bottom line is always money.” The humanitarian atrocities in Liberia, Sudan and Zimbabwe are nowhere near the scale of those in the Congo, but those are the wars it appears Bush wants to fight.

But the realpolitik nature of humanitarian crisis is not unusual, according to Gourevitch.

“Humanitarian motives for serious international action tend to be welcome packaging, as it were,” he said. “Even in Kosovo, it wasn’t a humanitarian war. There were a lot of strategic reasons for us to do it. This was NATO acting in the center of NATO’s turf on a problem it’d had for years, and that was then justified by the humanitarian motive, just as the humanitarian motive was then justified as a priority because we were a part of this strategic alliance.”

Leaving the Congo to the U.N. to handle has, in effect, been a convenient way of burying the issue. “It’s a place where you make a very modest and feeble gesture of concern in the form of sending an inadequately mandated small number of poorly armed troops … and then you can say ‘We’ve done something,'” adds Gourevitch. “And when it turns out you didn’t do enough and trouble comes as it did in Bunia in May, then everybody says ‘Well, look, it’s these Uruguayans under a U.N. flag, what a disgrace,’ and nobody says ‘Wait a minute, that was the program approved by Washington, Paris, London.'”

Certainly there are easier problems in Africa to solve. “The Democratic Republic of Congo is a country in name only … our policy options there are limited,” says Timothy W. Docking of the U.S. Institute of Peace. Although he says he’s hopeful Bush will address the Congo while in Africa, “the argument can be made that today we have limited resources, [so] let’s engage in places where we know we can make a change.”

In contrast to previous decades, this is what the Bush administration has done in Africa, Docking says. Clinton also was inactive in the Congo, despite his 12-day trip to Africa in 1998. “Africa’s never been a priority in American foreign policy. Even during the Cold War it was to confront perceived Soviet advances in the region … In the ’90s we really disengaged — cut USAID posts, downsized foreign aid.”

By any objective measure, he argues, sub-Saharan Africa has assumed a much greater priority under Bush. “Look at the AIDS funding,” he says, “the Millennium Challenge account, and the engagement in Sudan.” But though Clinton also turned a blind eye, the violence and deaths in the Congo have only increased under the Bush administration.

Scott Pegg, an activist and political science professor at Indiana University, believes it’s difficult to avoid the conclusion “that racism somehow is involved.”

“The example I sometimes give is in the early to mid ’90s, when everyone was focused on Bosnia, the killing and the starvation and the refugees were far worse in Angola and nobody cared,” Pegg says. “I just don’t think the American public or our leadership really views African deaths in the same light that they view European or other deaths.” Historian Gondola agrees. “Of course it’s racist,” he says. “It’s worse than racist … We turn on the TV and their faces are so remote. They’re darker, they’re marked by suffering, by famine, by disease. They don’t really resemble us. And because of that we create a gap, we almost deny them their humanity. So if they’re dying, it’s not human beings dying. There’s almost a sense that they deserve to die, because they can’t fight. And it’s very racist.”

Gourevitch points to a lack of stories in the news media. “If it were better covered in the news media there would be greater attention,” he says. “In that respect, the press seems to follow the priorities of the government rather than to set the agenda.” With the exception of the New York Times, coverage of the Congo has been erratic and sparse. One reason media coverage of Africa is so scarce is that response is so low. “Ted Koppel did a five-night series on the Congo in 2002, and the response was minimal,” says Anne Edgerton of the aid group Refugees International, who returned recently from the Congo.

But as far as Gourevitch is concerned, people don’t pay attention because the media have not made it a sustained story with daily coverage, as they did with Rwanda or the Balkans. “How do you get people to follow the Balkans? I’m sure they flipped the page at the beginning of the ’90s too. People weren’t itching to read about 50 people whose names ended in -vitch,” he said. And unlike Rwanda, “it’s not a genocide,” says Gondola. “It’s a war about valuable, non-renewable resources. It would be good if it were genocide, because then it’s normal to intervene.”

Docking points to both the size of the area and the lack of an advocacy group such as Israelis have in the U.S. “This is an enormous area,” he said. “There are 48 states in the region, and at any one time a third of them are involved in violent conflict … it’s hard to know where to dig in and engage. It’s also a continent we don’t have a lot of historical ties to, despite 12 percent of our nation’s population being able to trace their roots back to the region. For some reason, and this is the question of African-ness, Africa doesn’t have a strong constituency back here. In other words, African-Americans are not vocal … and have not formed effective policy pressure groups on American politicians, and a lot of us ask ourselves why that is.”

Gondola disagrees. “African-Americans are still fighting wars here. There’s still discrimination, still prejudice. They can’t fight wars on two fronts. [The Israel lobby] has power, they are better off as a group than African-Americans, so it’s easier for other groups as a whole to advocate for their places of origin.”

But regardless of the reasons why, there is not currently a national movement placing pressure on Washington, and no sign from the left of any grass-roots movement to protest U.S. inattention to the catastrophe. Act Now to Stop War and End Racism (ANSWER), a coalition of activist groups that protested the war in Iraq — especially civilian deaths — has also campaigned on Palestine and Cuba, but staffers in the group’s Washington and San Francisco offices said there are no plans in the works to protest the lack of U.S. involvement in the Congo. Top ANSWER officials did not respond to requests for comment about their lack of a campaign regarding the Congo.

Pegg believes it’s possible a protest movement could form, as they did around the issues of apartheid in South Africa and, to a lesser extent, conflict diamonds in Angola, but he wouldn’t bet on it. “One of the problems here,” he says, “is that there are a lot of different players involved, and it’s harder to put in a 30-second sound bite and have a clear ‘here’s the bad guy, here’s the victim.’ This one’s a little blurrier and messier, and I think that’s something that hinders [the forming of a strong activist movement.] If there was a clear campaign against a corporation that was benefiting from it … if something like ‘conflict cellphones’ or ‘conflict computer chips’ were to catch the imagination, that might be the route that that could happen.”

But unless something is done, the future of the Congo looks yet more bleak. “There’s no way the violence is going to stop until the conflict is ended at a very high level,” says Karin Wachter of the aid agency International Rescue Committee, speaking from Bukavu, a town in the east part of Congo. “Intervention has to come from the outside. It can’t come from the people standing up to it — they’re fairly powerless at this point. There’s so much keeping this conflict alive, and I’m absolutely amazed that this kind of conflict can exist without being given the attention it deserves, especially from the Americans.”

But as far as the U.S. government is concerned, “they’re going to be trying to avoid it unless it’s stuck under their noses,” says Gourevitch. “So let’s put it there.”

This story has been corrected since it was originally published.