For a few days this week the mood in Iraq recaptured that strange combination of elation and apprehension that marked those days in April right after Baghdad fell. The capture of the dictator on the run briefly rekindled the hope for a better future among the people who opposed his regime. His supporters, especially the Sunnis, seized on his capture just as they seized on the widespread looting after the invasion and made it the focus of their anger at the Americans. On the other hand, Saddam’s arrest has given hope to his victims that justice will be done, and a great sense of relief to those who were hedging their bets fearing that he would return to power. The optimistic scenario is that the resistance against the American occupation and a new Iraqi government, stripped of its only clear alternative, will lose momentum.

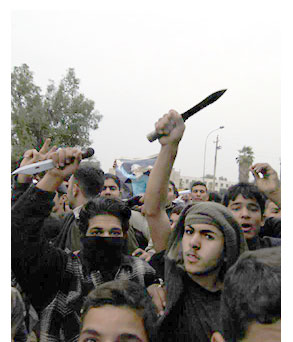

The capture has thrown into sharp relief the differences between the Sunnis who ruled Iraq for so long and the victims of Saddam — the Kurds and the majority Shiites. In many Sunni areas, people demonstrated in support of the dictator after his capture, leading to dozens of dead and wounded. This is in marked contrast to the Shi’a areas where people on the whole are relaxed and happy at the news.

And beyond the very different opinions Iraqis hold about Saddam — from vows to fight to the death in his name to demands that he be executed — there is one constant theme: anger and frustration with Iraq’s ongoing problems, from the current appalling lack of petrol and the electricity crisis to the continued lack of security.

Taken as a whole, the splits within the Iraqi people and the widespread dissatisfaction with security, power and lack of jobs point up the enormous task facing Americans and Iraqis alike as they try to effect a smooth transition from an occupied nation to a self-governing one.

In the sprawling and dirt-poor Shi’a neighborhood that bore the name of the former dictator, Saddam City, now renamed Sadr City after a Shi’a cleric who was killed by the regime, people are mostly overjoyed at the capture of Saddam Hussein. “Everybody here is very happy, we start a new life,” says Satar Razak, a 24-year-old proprietor of a vegetable and fruit stand in the market in Sadr City’s main street. “When people heard the news they all came to buy fruits and candies to hand out,” says Razak. The Shiites, like the Kurds in the north, have suffered most under Saddam Hussein’s rule. Razak says that his cousin was arrested by the regime in 1991 after the Shi’a uprising that broke out in the wake of the Gulf War had been put down violently, also in Saddam City. “They took him away and we never heard from him again,” Razak says. “We are sure he’s dead, executed.”

Most people in the market share his feelings of joy over the arrest of Saddam Hussein, although a few grumble about the sorry state of affairs of the country since the American invasion, about the interruptions in the power supply, about the petrol shortage and about the lack of security.

In the nearby Abrar mosque, Sheik Ali Mahmoud plays down the criticism of the Americans in his neighborhood. “Here in Sadr City our power supply was interrupted constantly as well under Saddam.” The population of Sadr City has heaved a sigh of relief after the arrest, Sheik Ali says. “Even after the Americans had liberated Baghdad, people were still afraid of Saddam Hussein,” he explains. Sheik Ali Mahmoud is himself a Sunni Kurd who fled persecution by Saddam Hussein’s regime in the north. His whole village there was destroyed by the government in 1977, he says. After that he came to Saddam City to lead the mosque. “It is not a problem, that I’m a Sunni Kurd in this Shi’a neighborhood,” Sheik Ali says. “We were disunited because of Saddam. He divided us with his violence.” Sheik Ali says he would like to see Saddam Hussein stand trial in Iraq — indeed, it is difficult to find a single Iraqi who favors an international trial. He expects the former leader to receive the death penalty. As for the Americans, the Sheik, like most victims of Saddam’s regime, does not agree with the widespread criticism of their performance. “They can stay as long as is needed to help us rebuild our country.”

Both questions — Saddam Hussein’s fate and the future of the American occupying forces — sharply divide the Shiites and Kurds, on one side, and the Sunnis on the other. In Tikrit, which is near the birthplace of Saddam Hussein and where he still has many supporters, demonstrations erupted in the wake of his capture, not far from the town. Any random conversation in the town’s main street will lead to choruses of “with out soul and our blood, we will sacrifice ourselves for Saddam.”

At the headquarters of the heavily Sunni Arab Salah-Eddin governorate, of which Tikrit is the capital, Maj. Derek Jordan says that there have been some disturbances since the arrest of Saddam Hussein. A civil affairs officer in the district with the 418th Civil Affairs Battalion, detached to the 122nd, Jordan was taken aback by the angry reactions in the area after the news of the capture. “Yes, I was surprised by the reactions. I had expected much more of a celebratory mood,” he acknowledges.

Jordan says the reason why the army is concerned about the demonstrations is that the Iraqis are not yet used to their newfound freedom to express their opinions peacefully.

“[The demonstrations] become a soft target for infiltrators bent on confrontation. People here are still getting used to such things.”

Dr. Muafak Saleh, a lecturer in biology at Tikrit University, where some of the demonstrations took place, concurs. “These are simple people — they shout very loud but they don’t know what they are saying.” The doctor thinks that most of the demonstrators either had some kind of stake in the former regime or that they were paid by loyalists to go out and make trouble.

But Saleh’s view is a minority one on the streets of Tikrit. More typical is Ibrahim Fadel Al Nasseri, who was a journalist for the “Tikrit Weekly,” a Baath mouthpiece that ceased publishing after the fall of the regime in April. Al Nasseri is from the same tribe as Saddam Hussein and utters platitudes such as “we need to protect him, he is our father.” He pours forth the familiar litany of complaints about the American presence, from broken promises of “bringing democracy” to the lack of security, electricity and the recent, interminable lines for petrol. He says that the Americans were tougher on Tikrit because of the search for Saddam Hussein. It is natural that his tribe and family would protect him, he says.

Ouja, just south of Tikrit, is where Saddam is really from and where some of his closest family members still keep houses. It is surrounded by American troops and barbed wire. Visitors can only enter with special permission and everybody who goes in or out is checked. Sheik Mahmoud Nidda is the head of the Nasseri tribe and of the sub-branch of the Beyat to which Saddam belongs. He is ambivalent about the capture of his family member. On the one hand he is furious with the Americans: “If Saddam had surrounded the village with barbed wire we would have fought him.” On the other hand he is embarrassed by Saddam’s survival.

“We are a tribe of brave men,” the Sheik asserts in his large, empty reception hall where normally dozens of people would come and seek an audience. “Saddam should have fought. He should have killed a couple of American soldiers and then he should have let them kill him, just like his sons Uday and Qusay did.” In Iraq, as indeed in the wider Arab world, people were shocked by the feared former leader’s meek surrender. “Maybe the people who took him his food drugged him,” speculates the Sheik. But then he acknowledges that he is just disappointed in Saddam Hussein. To Sheik Mahmoud it is a personal affront — and one that may also have consequences for his tribe. When the deposed dictator stands trial, many embarrassing details of the role his close family played under his regime may come out.

“It is obvious that the tribe profited from its connection with the leader of the country,” he admits. The sheik lives in a palatial villa on the edge of Ouja and the house and the reception hall exude power and money. But he says the advantage was a limited one and many people also talk of tensions within the tribe that resulted from its powerful position and its closeness to Saddam Hussein. One example is the feud involving Saddam Hussein’s son-in-law, Hussein Kamel, who was killed by his relatives after he returned to Iraq after having deserted. The Sheik does not want to elaborate on those dark chapters in his tribe’s history. He does say, however, that things were not all that rosy. “Saddam Hussein took the young men from the tribe and mainly used them in his personal security detail,” he says. “That did not usually mean a lot of money or power but it does mean that we are hated by many people in the country.”

The Al Nasseri tribe has more than 350,000 young men across Iraq, he says, making it a very powerful group. Ouja has a population of some 25,000 people. The 60-year-old sheik says that he personally is a monarchist, not a Baath member like Saddam Hussein. He emphasizes the political differences he had with the arrested leader. In the early ’90s he was even forced out of his position, he says, and Saddam Hussein appointed somebody else as head of the tribe. “He is now dead. He was killed two months ago,” he says without elaborating. Despite these differences with Saddam Hussein, he says it is impossible that somebody from his own tribe would have betrayed their relative.

“In Iraq, family ties are more important than political differences,” he says. The sheik points out that Saddam Hussein was arrested in Durra, a village just to the south of Ouja. “We did not even know where he was,” he says. In Ouja, where just a few people can be seen in the streets, many people still support Saddam Hussein, but the Sheik says he hopes the violence will now fade. “Saddam Hussein has been arrested, why should people fight on for him?”

Sheik Mahmoud is reluctant to say what he thinks should happen now to Saddam Hussein. “Release him?” he says doubtfully, knowing that this is not an option. Certainly he believes the former leader should not receive the death penalty now. “He should be treated as what he is, the former president of the country.”

Some of those who suffered under Saddam Hussein take a very different position. “I can’t believe the Americans treated him so well, I was furious when I saw it,” fumes Hussein Ali Al Saberi. One of the directors of the Najaf branch of the Union of Political Prisoners in Iraq, he speaks with frustration about the capture of Saddam Hussein. “When I was taken by his men, they beat me and tortured me with electricity,” Al Saberi recalls. He does not advocate the same treatment for Saddam Hussein, but he says he would have liked to see him a bit less relaxed about his capture.

“We understand there are new rules now. We want to belong to the rest of the world and we know that Saddam has to be treated according to international norms,” says Al Saberi. There is, however, one issue on which there cannot be a compromise for the former political prisoner. “For this man who has caused so much evil there is only one punishment, the death penalty. Even if he is only convicted of one of his crimes he should be executed.”

Al Saberi was arrested in 1987 for staying away from work in a campaign of protests against the regime. He was a member of the Islamic Dawa party that very early on started resisting Saddam Hussein and whose members were persecuted by the Baath party government. “There was a group of us, some 25 people,” recalls Al Saberi. They executed about half and the other half, they tortured.” He was released after the Shi’a uprising of 1991 but that was not the end of it. “I was not allowed to travel, I could not work, they followed me all the time. It was not a life.”

Some of the worst deeds of the regime, according to the people in Najaf, followed the Shi’a uprising of 1991 (also called the intifada), which Saddam put down mercilessly. Everybody in Najaf seems to have suffered directly at the hands of the government or to know at least one person who has. Many men are missing an eye: beating the eyes appears to have been a favorite punishment used by Baath supporters on their critics.

An unpaved, muddy alleyway near the Imam Ali mosque in the center of Najaf, the holiest Shi’a shrine, leads to the simple home where the Hamudi family lives in dire poverty. The mother has been ill since her eldest son, Ra’ad, was taken away by government soldiers during the 1991 uprising. His sister Hebba was very young at the time but she has heard the story told many times. “Ra’ad was wounded in his leg during the fighting and it had to be amputated. When the soldiers entered the city we fled but Ra’ad and some other men who were wounded stayed in the house,” tells Hebba. “They took everybody away and we have not heard from them again. They were all executed,” she says.

Hebba and her family hoped to find at least the remains of Ra’ad when the mass graves were discovered after the fall of Saddam Hussein. “But we are still looking,” she says.

She says that she and her family feel better after the capture of Saddam Hussein. “We are not afraid anymore of him or his supporters.” But Hebba’s hatred of the dictator is undiminished. “He should just be handed over to us and he’d be lucky if we drank his blood.”

Everyone in Najaf seems to agree: The man who caused the city so much suffering must die. The supporters of the different Shi’a clerics who influence the whole community from this holy city concur. Ali Merzah Al Asady is one of the leaders of the Dawa party in Najaf. Like so many of his colleagues he was arrested and tortured under Saddam Hussein. He is clear about what the punishment for the dictator should be. “Some people are talking about life in prison, I think it is better to end his life.”

Al Asady is furious at what he sees as unwarranted international meddling in the question of what should happen to Saddam Hussein. He is particularly scathing about the suggestion, raised by U.N. Secretary General Kofi Annan among others, that the captured ex-president should stand trial in front of an international body. “So, what are they going to do? Take him to The Hague and treat him like a king just like they are doing with the Yugoslav president? So that he has to appear only now and then in court where he can brag about what he has done?” To Al Asady that is the worst possible solution from every point of view. He wants to see a trial in Baghdad.

“In Baghdad his victims will be able to attend the trial, there will not be such long delays and even if he is convicted of one crime, he will get the death penalty, which he deserves.” He does not agree that Iraq is too fragile at the moment to accommodate such a trial. He thinks the people in the Sunni areas who demonstrated in support of Saddam Hussein after his arrest are only a minority, “who have probably been paid.”

Al Asady thinks he speaks for the large majority of the population of Iraq when he says, “Everybody will be glad to see the end of Saddam Hussein.”