Because rock ‘n’ roll is a relatively new art form, we’re only just now seeing what happens to people who have, from a very young age, devoted their lives to spreading its gospel.

The subject of George Hickenlooper’s “Mayor of the Sunset Strip” is Rodney Bingenheimer, a shy, soft-spoken elf of a man who came of age in Hollywood during the ’60s (the young Sonny and Cher were like surrogate parents to him) and went on to become one of the most beloved, respected and instinctive DJs of the ’70s and ’80s.

Bingenheimer broke countless bands, including Blondie, the Ramones, Van Halen and the Go-Go’s, and his show, “Rodney on the Roq,” on KROQ in Los Angeles, became a lifeline for anyone hungry for new music. Bingenheimer used his remarkable radar to search out great songs, done by people you hadn’t heard of (yet), and sent them out on the airwaves before other radio stations would even touch them. You could argue that he played as big a role in shaping the rock ‘n’ roll culture of the era as the artists themselves did.

But few people outside Los Angeles even know who Bingenheimer is. And his show, once a must for anyone within listening range who wanted to stay on top of new music, is now relegated to one minuscule nighttime slot. As one of his younger KROQ colleagues says, not unsympathetically, in the film, Bingenheimer is now considered by the station to be the “king of the obscure … the gateway to things people care about” — and here, he adds a pause that speaks volumes — “less.” Now that radio is all about programmed playlists, it’s no longer valuable, or even advisable, for a DJ to have killer instincts. Or even just ears.

Hickenlooper is a smart young filmmaker who co-directed the 1991 “Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse,” which documented the making of Francis Ford Coppola’s “Apocalypse Now.” More recently, he gave us the flawed but inescapably elegant “The Man From Elysian Fields.” Here, Hickenlooper doesn’t set out just to tell the story of an unsung hero (although that’s surely part of his goal). He’s deftly filling in a much bigger picture, a sprawling, abstract canvas, rendered in some pretty melancholy colors, about the ways our love of music can affect our lives: Sure, music enriches us. But the rough truth is, it can also beat the crap out of us. I’ve heard more than one musician reflect ruefully, “Music ruined my life” — in other words, the love of it spoiled them for anything else.

Yet even if Bingenheimer’s celebrity and influence have declined in recent years, Hickenlooper doesn’t make him an object of pity. That may be because Bingenheimer doesn’t see himself as an object of pity, even though it often seems that he’s thrown much of his energy into building the careers of others while not being particularly devoted to bulking up his own. Bingenheimer is charming, understated and waiflike. His hairstyle has undergone some minor changes over the past 40 years, having settled into something that’s half Ron Wood rooster cut, half Dutch-boy bob, but also weirdly timeless. His eyes are serious, inky and honest. When Hickenlooper, off-camera, asks him a question, he answers with so much unrehearsed forthrightness that you realize it would never occur to him to lie or embellish. In fact, his longtime friend, the nefarious producer and heel-about-town Kim Fowley, builds up Bingenheimer’s legend more than Bingenheimer does, informing us that, in the ’60s, Robert Plant noted that “Rodney gets more girls than I do.”

It’s easy to see how girls in ’60s Southern California would have gone wild for the teenage Bingenheimer, who looked like the innocent little boy every girl wanted to mother (and more). But Bingenheimer didn’t have a particularly glamorous upbringing. He grew up in the small California town of Mountain View. His parents divorced when he was 3. His father went on to remarry and, as he practically admits in his on-camera interviews here, had little to do with Rodney’s upbringing. Rodney was closer to his mother, who died several years ago, but even that relationship is a bit shadowy: Bingenheimer was left on his own at a young age, roaming Sunset Strip and somehow (it’s never made clear exactly how) meeting and befriending the most sensational musicians of the day, from Mick Jagger to Elvis Presley to David Bowie.

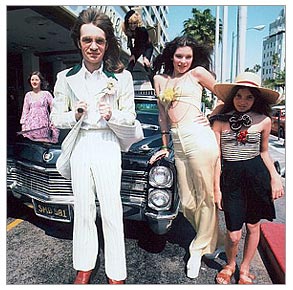

Hickenlooper mixes contemporary and vintage footage, crisscrossing the past and the present to sift out every possible fleck of glitter from Bingenheimer’s sometimes glamorous, sometimes pedestrian, career. Zelig-like, Bingenheimer shows up in photograph after photograph, as well as in live-performance footage, sidled up to the big stars of the day. He was never a stone’s throw away from a photo op with the likes of the Doors, the Mamas and the Papas, Jimi Hendrix, Bob Dylan and Frank Zappa.

Apparently both persistent and likable, Bingenheimer became a fixture on the Hollywood scene of the mid- to late ’60s. His glamour quotient increased further when he tried out for the Monkees. (He didn’t make the cut, but he resembled Davy Jones closely enough that he did serve as a Monkee stand-in now and then.) Somehow, everybody who was anybody knew Rodney. In the early ’70s he opened a club known as Rodney’s English Disco, which featured a tiny roped-off VIP area that was barely separate from the space where the club’s garden-variety beautiful people shimmied and shook.

Not long after the disco closed, in 1976, Bingenheimer got his slot on KROQ, and his web of rock star (and rock star wannabe) acquaintances continued to grow. Hickenlooper interviews a starburst array of them, including Blondie’s Debbie Harry, former groupie extraordinaire and ex-GTO Pamela Des Barres, Doors keyboardist Ray Manzarek, Brooke Shields and Nancy Sinatra. Courtney Love recounts how she met Bingenheimer: “I stalked him.” And Des Barres, looking prettier and more vivacious than many women half her age, reveals that Bingenheimer was the first boy she kissed when she got to Hollywood. “He tried to feel me up, but I wouldn’t let him!” she adds, breaking into a fit of giggles.

We learn more about Bingenheimer from these interviews than we do from what he says about himself, which is actually very little. Nearly everyone speaks of him both fondly and a little protectively, particularly Cher, who explains that she and her ex-husband Sonny Bono really liked Bingenheimer and were happy to have him hanging around — a good thing, since he obviously hung around a lot. David Bowie, a busy man with much bigger fish to fry, speaks with Bingenheimer on-camera, clearly having made time to do a favor for someone who helped him out early in his career. Bingenheimer meekly points out that the not-yet-famous Bowie used to send him demo tapes. Bowie retorts that those tapes are now “extremely valuable” and then goes on to ask, perhaps only half-kiddingly, if Bingenheimer has sold them off.

Bingenheimer murmurs that he hasn’t, and although the guy clearly lives modestly — he putt-putts around town in his mother’s old Nova — you don’t doubt him for a second. Bingenheimer takes us on a mini-tour of his home, showing us all the memorabilia he’s accumulated over the years, including Elvis Presley’s driver’s permit. Hickenlooper asks him, marveling, how he got it, and Bingenheimer replies, straight-faced, “He gave it to me.” Now somewhere in his 50s, Bingenheimer dresses as if somewhere in the late ’70s he found the uniform that worked for him and decided to stick with it: He favors narrow dark trousers and a boxy black jacket that all but swallows his trim, slight frame. His stride is a bit tentative, but there’s always a bounce in his step — he’s like a wooden puppet with hidden springs in his joints.

While Hickenlooper never takes the cheap route of making Bingenheimer a figure of pity, he manages to capture the halo of sadness that hovers around the man. Bingenheimer has a close friend named Camille, a tall brunette with an intense, but not unkind, demeanor. It’s obvious the two care for each other, but bit by bit we catch glimpses of the nature of their relationship. It becomes clear that Bingenheimer has romantic feelings for Camille, whereas she announces, almost flatly, that she “has a boyfriend, and Rodney’s just a friend.”

There are plenty of other moments in “Mayor of the Sunset Strip” that aren’t easy to shake, as when Rodney visits his father and stepmother’s house and they explain that Rodney’s picture isn’t among the family photographs they have displayed prominently in their living room. “They’re in the other room,” the stepmother explains. Rodney heads for that other room and digs through some carelessly stacked pictures to pull out a snapshot of himself, age 4 or so, with the Easter Bunny. His stepmother looks on, musing idly, “Dad’ll have to put that in a frame.”

Yet “Mayor of Sunset Strip” isn’t a downer. Bingenheimer admits, only at Hickenlooper’s prodding, that he could use more money, a comment that’s particularly wrenching considering that Bingenheimer has helped his share of down-and-out dreamers over the years (one of whom, a 50ish transplanted Texan who wants desperately to be a rock star, is interviewed in the movie). It’s possible that some of the acts Bingenheimer has brought to prominence over the years have helped him out financially; if they haven’t, they need to seriously consider it. (Liam and Noel Gallagher of Oasis, to name just two, can surely afford it.)

But what comes through most vibrantly in “Mayor of Sunset Strip,” shining through Bingenheimer’s low-key, laid-back, almost monotone manner of speaking, is how much the music has meant to him, even if it never exactly lined his pockets. One of the movie’s most beautiful sequences is a bit of footage filmed during one of Bingenheimer’s fairly recent radio shows, in which he plays for his guest, Brian Wilson, Ronnie Spector’s 1999 recording of the song Wilson wrote for her, “Don’t Worry Baby.” (Phil Spector refused to let her record it when it was written.) Wilson’s expression melts into pure ecstasy at the sound of that voice, at last performing his song. Bingenheimer looks on, clearly filled with a kind of impish pleasure at being the agent of such unadulterated happiness.

At one point Hickenlooper, from behind the camera, asks Bingenheimer what he likes about pop music. Bingenheimer shrugs impatiently, as if he were annoyed by the question, and you can’t blame him. How would anyone answer that? Bingenheimer thinks for a second and then says, “It makes you happy. It makes you wanna do more things.” And, he might have added, like the best friend you’ve got, it sticks with you for a long, long time.