Last week, as the Bush campaign and the news media continued to question John Kerry’s heroism during and after the Vietnam War, I detected the beat of what I call the Bush family’s Texas two-step: “Wimp” your opponent, then “weird” him. Make him look soft on defense, then show him to be out of touch with the lives of ordinary Americans.

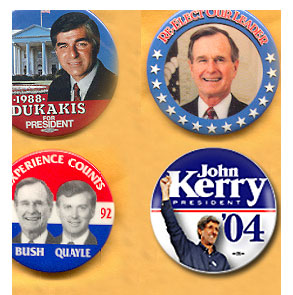

When I discussed this with a friend from Bush War I, the one against Michael Dukakis (I made TV spots for Dukakis during the presidential primaries), we were struck by the banality of the Bushes’ strategy. In 1988, opposing Dukakis, they ran against a Massachusetts liberal. In 2004, opposing Kerry, they’re again trying to run against a Massachusetts liberal.

Note the shorthand: “The senator from Massachusetts has given us ample grounds to doubt the judgment and the attitude he brings to bear on vital issues of national security,” Vice President Cheney charged in a political diatribe delivered at Westminster College in Missouri — one that offended the college president so deeply he immediately invited Kerry to speak in response.

Just as Kerry began national TV advertising focusing on his combat service, the Bush attack Hummer swung into action. With guidance from an anti-John McCain, pro-Bush publicist, a group of veterans fragged Kerry in an attempt to dishonor his exemplary military duty. As Joe Conason wrote in Salon last week, one of the Kerry-hating veterans, Texas lawyer John O’Neill, “has been assailing Kerry since 1971, when the former Navy officer was selected for the role by Charles Colson, President Nixon’s dirty-tricks aide.”

“I do not believe John Kerry is fit to be commander in chief,” retired Rear Adm. Roy Hoffmann said May 4 at a news conference. Hoffmann first gained notoriety in Vietnam as a Robert Duvall-type character (the cowboy commander in “Apocalypse Now” who loved the smell of napalm in the morning), a strutting, cigar-chewing Navy captain obsessed with body counts.

Sadly, such attacks are nothing new to Democrats running for president. Republicans have been painting Democrats as dangerously soft on defense since Nixon massacred George McGovern (an honest-to-goodness World War II hero bomber pilot) in 1972. The modest McGovern chose not to discuss his heroism during that campaign; in the Midwest, such a declaration would have been considered boastful. Besides, he was the antiwar candidate. That year, Massachusetts became enshrined as America’s most liberal state when it was the only state in the union to choose McGovern over Nixon. At the same time, in the same state, an antiwar Vietnam veteran lost a race for Congress. His name: John Kerry.

In 1988, Dukakis captured the Democratic presidential nomination in a manner not unlike Kerry did in 2004 — by winning a war of attrition. Flush with money, Dukakis was the last man standing: First Gary Hart, then Bruce Babbitt, then Paul Simon, then Richard Gephardt, then Al Gore and finally Jesse Jackson all folded their hands. Those of us in the Dukakis message camp quickly grasped what is known in advertising as your USP, or unique selling proposition. What can you say that both is compelling and no one else can say? I concluded it was that Dukakis was the only CEO in the field, the only governor, the only candidate who had balanced budgets, raised and lowered taxes, put police on the streets to fight crime, and reformed a cruel and dysfunctional welfare program. Undeveloped, however, this USP contained a fatal flaw. The weakness became apparent when Dukakis appeared in an early televised debate against conservative windbag William F. Buckley. But Governor, you have never had to command or raise enough funds for a military to defend America from its enemies abroad, Buckley droned snidely. The first wimp charge had been leveled.

One of the urban legends that persist about Dukakis is that he never fought back, never ran a negative TV spot. But that is not true, as I explain shortly. His distaste for first use of negative attacks grew out of the darkest day of his campaign, the day he dismissed John Sasso, his campaign manager, muse and auteur. Dukakis had painted himself into a corner when he self-righteously promised to dismiss anyone who had been involved in producing a video that showed candidate Joe Biden appropriating the life story of British politician Neil Kinnock. Without telling Dukakis, Sasso sent the tape to the New York Times, NBC News and the Des Moines Register. Biden may have been caught in a lie, but in Dukakis’ eyes, the graver sin was that Sasso denied to the press that the campaign had had anything to do with the tape.

By ditching Sasso, Dukakis planted the seeds of his own demise. Although the candidate had literally cut off the head of his campaign, Sasso’s plan would get him the nomination. But Sasso hadn’t gotten to the general election plan.

The subject of negative campaigning didn’t come up again until shortly before the delegate-rich Super Tuesday primaries, held mainly in the South. Dukakis had just lost the South Dakota primary to Gephardt, who used a last-minute TV spot to belittle Dukakis for suggesting that Midwestern farmers should do what Massachusetts farmers had done — diversify and grow Belgian endive. Distorted and simplistic, the endive spot nevertheless cost Dukakis the state.

Unbeknown to Dukakis, I had produced a TV commercial about Gephardt in case we needed it. The spot showed an acrobat, with his hair sprayed red, in a business suit doing somersaults and cartwheels, backward and forward, as an announcer described the flip-flops in Gephardt’s record in the House. One week before Super Tuesday, I flew to Miami to show Dukakis the spot. His best friend and campaign chairman, Paul Brountas, was there, along with a few Florida politicians. After viewing the spot, Dukakis grimaced, shrugged and threw up his hands. “I don’t know, guys, what do you think?” They said it was clever, memorable and, most important, necessary. Dukakis ultimately relented, and the ad ran only two days. Gephardt lost every Super Tuesday primary but his home state and quit the race a few weeks later.

By the time Dukakis traveled to Atlanta to accept his party’s nomination, I, seen as a holdover from the Sasso team, had been replaced by a new creative group hired by Susan Estrich, Dukakis’ new campaign manager. So I was surprised when Estrich asked me if I would produce a biographical video for the convention. Academy Award-winning actress Olympia Dukakis, the candidate’s first cousin, had volunteered to help. We decided she should play guide in a short film that would show her cousin’s roots in a house in Brookline, a Boston suburb where John F. Kennedy was born. The first time we scouted the location, I told the director, “This is perfect. It [looks like] Ward and June Cleaver’s house” in the TV show “Leave It to Beaver.”

My enthusiasm flowed from what the house said about Dukakis as a quintessential suburban kid with a normal, post-World War II upbringing. The idea was to show that Dukakis was a fully assimilated second-generation American. He had married his childhood sweetheart, took the subway to work, followed Boston sports, and was tight with a buck. The contrast with the privileged upbringing of George H.W. Bush, himself a native New Englander, was irresistible. But Dukakis would have none of what he called “that class-war stuff.” Perhaps it was because he thought of himself as fortunate; his father had been a doctor, his mother a teacher, and they had expected much of him.

In Massachusetts, Dukakis’ toughest campaigns had been against Democrats — conservative Irish Democrats; big, brawling Roman Catholic men who subscribed to old-style relationship politics; men who held ideals about helping the poor but who saw nothing wrong with helping some of their friends along the way. By the time Dukakis got to general elections against Republicans, the competition was so light he could start picking a cabinet and writing legislation. Kerry’s path as a politician has been considerably harder; as a senator, he has had to beat formidable Democrats and Republicans, the toughest being the wily and popular former GOP governor of Massachusetts, Bill Weld.

What’s more, at the Statehouse, Dukakis had won and lost a governorship as a reformer. He was about process, not outcomes; if the process was honest and fair, the results would take care of themselves. By extension, the campaign for president, Dukakis famously preached, was about competence, not ideology. Right after winning the nomination at the 1988 convention, Dukakis took off for a three-week sabbatical in the Berkshires. While there he decided he needed a new management team, new media producers, a new (and utterly implausible) plan to do door-to-door canvassing in California, but nothing new on message. Nothing.

Meanwhile, on the other side, the Bush team of Lee Atwater, Roger Ailes, James Baker and Peggy Noonan had no choice but to use the wimp-and-weird strategy against their opponent. A poll released right after the Democratic convention showed they were trailing by 14 points. Thus began the Republican version of Charles Manson’s “helter-skelter.” The GOP threw everything at Dukakis. They attacked him for mental problems (John McCain, are you listening?); his veto of a Massachusetts bill requiring public but not private school teachers to recite the Pledge of Allegiance; his “lax” furlough program; his membership in the ACLU; the filthy Boston Harbor (supposed proof that the “Massachusetts miracle” was a scam); and his refusal to support the death penalty, even for CNN’s Bernard Shaw, who posed a difficult question about the issue in a presidential debate. This was carefully designed helter-skelter — there was no pattern, but the bottom line was, this guy is not like the rest of us.

The best example of how helter-skelter works is detailed in Sidney Blumenthal’s “Pledging Allegiance” (1990). One of the most stubbornly stable people I have ever met, Dukakis was accused in a flier produced by followers of the loony Lyndon LaRouche of having a history of mental problems. Soon the archconservative Washington Times picked up the charge. Then the longtime anti-Dukakis Boston Herald tabloid trashed him for refusing to discuss it. Then the even more conservative Detroit News sent Dukakis a nutty questionnaire about his mental health, which Dukakis refused to answer. He believed the charges were so preposterous that no one would believe them. Besides, this doctor’s son felt the question itself was an unethical breach of patient confidentiality, even if there was nothing to report.

Dukakis finally agreed to release his entire medical file. But the damage had been done. President Reagan was asked at a White House press conference by a LaRouche-nik for his thoughts on the reports about Dukakis’ mental health. “Look, I don’t want to pick on an invalid,” Reagan replied. From a LaRouche flier to a presidential press conference, all in a few weeks, it was helter-skelter on speed.

Republicans also attacked Dukakis for allowing a weekend furlough for a convicted black felon, Willie Horton, who had attacked and raped a white woman — under a program begun by Dukakis’ Republican predecessor. “When we’re through, people are going to think that Willie Horton is Michael Dukakis’ nephew,” said political consultant Floyd Brown of Americans for Bush. By making the spot, Brown’s group allowed Bush and Ailes to deny that they had hatched it. (Brown’s group would later pump up the Whitewater pseudo-scandal against the Clintons, once again sucking in the press corps.)

One of the strangest ironies of the 1988 campaign involved Bush’s revolving-door furlough TV spot, a brutally effective black-and-white commercial that showed criminals — with swarthy complexions — moving in and out of jail through a turnstile. One of the creators of that spot was himself on furlough for vehicular homicide he had committed while driving drunk. News of this hypocrisy reached me only days before the general election, too late for Dukakis’ team to do anything with it. Why remind people of the whole Horton furlough thing? Besides, the lights were flashing “Game Over.”

Returning to 2004, Kerry, a former assistant district attorney with mob convictions on his résumé, and good relations with prosecutors and police chiefs, is tough to attack on crime. He also aggressively investigated U.S. officials’ actions in the Iran-Contra arms scandal, exposed the CIA’s secret deals with brutal Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega, and uncovered a crooked international bank with ties to longtime Washington fixer Clark Clifford. Nevertheless, without primaries to provide introductions and context, Kerry has been fast-forwarded into a pre-election situation in which he is widely familiar but not well known — making him, by the Bush campaign’s lights, the perfect target for turning into a liberal wimp.

As mentioned earlier, the Bush camp decided to preempt Kerry’s claim to wartime heroism by rolling out a bogus, ad hoc group of anti-Kerry veterans, and now both sides are running multimillion-dollar advertising campaigns on Kerry’s military service and voting record. Kerry and many of his people believe that, unlike other Democrats, he should be able to repel the classic Bush and GOP soft-on-defense attacks because of his combat valor. He won’t easily be turned into a wimp on defense, no matter how many ways they try to call him French. His Vietnam service is the political equivalent of the family jewels — and Kerry will protect it at all cost.

When Kerry ran for Congress 32 years ago and lost — a campaign in which I participated — he was attacked by a previously unknown Vietnam veterans group. Eventually, President Nixon’s chief political hatchet man, Colson, confessed to setting up shell veterans groups to embarrass Kerry and give local newspapers fodder for Kerry attacks. With new anti-Kerry veterans groups being formed seemingly every day, will anyone in the media besides Salon and a handful of others look into these Kerry critics and their sponsors? Not likely. It’s easier to Google the Dutch painter whose work of art Kerry sold last year.

Meanwhile, the White House continues to stonewall on President Bush’s so-called military service. All records have been made public, the White House’s boy press secretary repeats, when of course they haven’t. Releasing the details of Bush’s dental checkup was a public relations coup. We are so open, the White House boasted, we even released the president’s dental records. I would have preferred viewing the teeth of someone who’d seen Bush in the Alabama National Guard. And Bush’s losing his flying credentials because he didn’t show up for a mandatory pilot’s physical? That too is “old news.” But what Kerry did in 1971, when he was an angry 27-year-old fresh from the killing along the Mekong River — that’s still relevant.

We are at once in a new and familiar place. We stand in the ridiculously early, post-primary, pre-convention period, but we already know the principal actors, their supporting casts, their lines, their points of conflict and, thanks to polling, even their story arcs. We also know that the news media — new and old alike — are hardly neutral observers or faithful recorders of events and utterances. They are a snarling Greek chorus.

Mainstream media appear to swallow what the GOP feeds them — whole. Reporters lurked for days around a story ginned up by right-wing gossip Matt Drudge that turned out to be a phony “intern” flap. The media have failed to find out from Commerce Secretary Don Evans why Canada’s economy has been growing jobs while our economy has been losing them, according to a report by the Center for American Progress. Yet they eagerly tell us that Evans is the man who said, “Kerry looks French.” The Web site of a certain onetime drug-addled, right-wing radio talk show host carries pictures of the Kerry-Heinz homes, with captions in English and French. The homes and their prices were also featured recently in major newsweeklies.

While the most secretive vice president in history attacks Kerry’s fitness to lead America in a time of war, major media cover Roman Catholic conservatives’ questioning of Kerry’s fitness to receive Communion. Teresa Heinz’s eight cars are national news; the fact that Laura Bush killed someone while driving one car is put aside as “old news.” Meanwhile presidential brother Jeb Bush twists an admitted — and corrected — mistake by a Florida college newspaper into a statewide story that says Kerry favors expanded oil drilling off the Florida coast.

How might Kerry run the government? What kinds of issues have mattered to him as a senator? What would a Kerry budget look like? Who are the policy people he turns to for advice? “Yeah, yeah, yeah, we’ll get to that. But what about the starlets, Senator?”

If Kerry had had his way, Cheney smeared, Saddam Hussein would still be in power. Cheney, who used five draft deferments to avoid military service during the Vietnam War, dared to challenge the commitment of Kerry, a decorated Vietnam veteran who volunteered to fight in that war, saw death up close, and carries a piece of shrapnel lodged in his arm.

A Bush commercial attacks Kerry’s votes against old weapons systems that are suddenly deemed necessary to today’s war on terrorism. But as President Reagan’s secretary of defense, Cheney had called for many of the same cuts he now faults Kerry for favoring. Moreover, Cheney had urged deep cuts in troop strength of anywhere from 100,000 to 500,000 active and reserve forces.

ABC News “discovered” a tape given to it by the Bush campaign that showed Kerry saying he had thrown his military medals over a fence around the U.S. Capitol when he and thousands of other veterans protested the war they had fought. (The ABC producer for the story was Chris Vlasto, a contributor to right-wing publications, who was also a producer of much of the network’s pseudo-scandal coverage during the Clinton years.) The national news media fixed on the “gotcha” aspect, the fact that Kerry had told a news organization 33 years ago that he had thrown medals, not ribbons. Today Kerry says they were ribbons. What does this tell us about Kerry that we need to know, other than the fact that a 27-year-old veteran was filled with anger and confusion and profound regret over what his government had asked him and thousands of other American soldiers to do? Whatever he threw, the act crushed him, as a Boston Globe photo of a crumpled Kerry reveals. Not far from where he and his mates had surrendered their combat decorations, he slumped to his knees, his first wife huddled over the solitary, broken soldier.

Kerry’s campaign has been distracted by vacations, shoulder surgery and the tragic news coming out of Iraq. Challengers often forget that they have to keep introducing themselves to voters. The Kerry campaign is launching a $27 million TV advertising campaign to fill in the gaps, and to protect the family jewels.

My view, shared by some but certainly not all in the Kerry campaign, is that as long as the subject is Vietnam, Kerry is ahead of the game. In Massachusetts, his military service is considered to be the third rail of Kerry politics. Touch it at your peril. Former Massachusetts Gov. Weld, having watched others get jolted, had nothing but praise for Kerry’s military service.

We may look back at this period and see that just when Bush looked as if he was on the ropes, talented GOP handlers saved him. Bush is managed by people who know how to sell him. Texans all, they created him — from diaper changer Karen Hughes to dark lord Karl Rove to Democratic turncoat and media consultant Mark McKinnon.

Most in the Kerry campaign know what to expect from the Republican mule drivers. They know, for instance, that Democrats having their convention in Boston, while not ideal, will matter not one whit to average voters in swing states four months later. But the national news media seem poised to treat liberal Massachusetts as a major story. When gay marriages become legal in Massachusetts on May 17, and national media fan out across the state to document same-sex nuptials, the Bush administration will try to make the whole thing Kerry’s idea.

Last week, Republican Gov. Mitt Romney of Massachusetts did his part, promoting a “foolproof” death penalty plan that would use DNA and other scientific tests to encourage the imposition of a death sentence. While it is unlikely to gain legislative action, much less approval, the plan will provide the Bush-Romney team with live ammunition when the Democrats come to Boston to nominate Kerry in late July.

Whether the Texas two-step succeeds will depend in large part on the toughness and discipline of Kerry and his campaign. It will also depend on whether members of the news media use this early phase of the campaign to find better ways to cover the race, the smears and the candidates — or approach the Bushes, as they have so often done, on bended knee.