The distance from amusing to annoying can be a matter of one step or, in the case of David Brooks, a brief, ignominious, muddy slide. Brooks has been hilarious and original in his social and cultural essays for the Atlantic Monthly and in “Bobos in Paradise,” his book about the vicissitudes of the baby boom generation, but his more recent stint as an Op-Ed columnist for the New York Times is a case of the Peter Principle in action. Brooks is out of his depth, as his recent flailings on the Iraq war have made painfully clear. It’s enough to make you yearn for his return to the territory of “Bobos,” where Brooks acquitted himself so well. Then along comes his new book, “On Paradise Drive,” to prove once again that you should be careful what you wish for.

Admittedly, Brooks is in an impossible position. Liberals are forever claiming that they’d be happy to read a conservative writer if only the press would publish one who wasn’t a moron or a hateful, irrational liar. Brooks is supposed to be that writer. He is not, for example, all that conservative, especially on social issues, and he’s neither a snoot of the old school like William F. Buckley Jr. nor a venomous hypocrite like Rush Limbaugh nor, God forbid, a borderline sociopath like Michael Savage.

But although they won’t admit it, most liberals secretly believe that no one sensible and decent could ever seriously entertain conservative ideas, and therefore no one could ever fulfill the platonic role of Acceptable Conservative. It’s a Catch-22 situation Brooks has stepped into. Still, his lack of consistency and intellectual chops certainly hasn’t helped his case any.

What does work for Brooks is what he accurately identifies as the provincial complacency of the people he both writes for and skewers, the intelligentsia on the coasts and in the handful of inland blue states. His brief is to explain the mores and mind-set of the great flyover to overeducated, full-of-themselves urbanites in a way that needles their unthinking disdain for such places. This wouldn’t get him very far, of course, if those urbanites didn’t lap this stuff up, or if the readership of highbrow magazines and the newspaper of record didn’t include lots of people who feel both resentful of and somewhat intimidated by what used to be called the Northeastern elite. Class animosity lives on in America, however much Brooks may claim otherwise.

Also, Brooks is funny, a rare quality among social critics. This serves him well when he’s on his own turf, describing the trappings and preoccupations of the way we live now. (On subjects requiring gravitas — the current war, for example — he’s stripped of his chief rhetorical tool, and the result has been a sorry sight to behold.) However, the ideal format for Brooks’ wit is the 1,000-word column, a length ideally suited to a riff on the psychosexual symbology of outdoor grills, the future market for play-date attorneys or the rituals of the business traveler. String a bunch of these riffs together and you get … a bunch of riffs strung together, or, in the case of “On Paradise Drive,” the riffs plus lots of pithy quotes from the likes of Alexis de Tocqueville, George Santayana and Walt Whitman, glued together with dollops of fuzzy, self-contradictory “analysis” from Brooks himself.

Brooks’ fans see him as wickedly irreverent. That image is based on his mastery of a single technique (and not a particularly original one, since it was first used by historian Paul Fussell in his 1983 book “Class: A Guide Through the American Status System”): He details, with the taxonomic precision of a zoologist, the habits and possessions of American social groups. “On Paradise Drive” takes a highly selective “tour” through a series of representative neighborhoods, starting from the city and heading out. Brooks describes the hipster enclave of “Bike-Messenger Land,” where “You’ll see transgendered tenants-rights activists with spiky Finnish hairstyles, heading from their Far Eastern aromatherapy sessions to loft-renovations seminars.” Then come the “Crunchy Suburbs” where he observes “the sudden profusion of meat-free food co-ops, the boys with names like Mandela and Milo running around the all-wood playgrounds, the herbal soapmaking cooperatives,” etc. Then there’s the “Suburban Core,” where “all those things that once seemed hopelessly outré — cheerleaders, proms, country clubs, backyard barbecues and stay-at-home moms — still thrive.”

And onward, to a new phenomenon that Brooks considers highly significant, the exurbs. Here, where once was empty land for miles, subdivisions arise and are populated in a matter of months, and “you can cruise down flawless six-lane thoroughfares in trafficless nirvana.” In these friction-free “Mayberries with Blackberries,” the development trend called new urbanism has dictated the construction of artificial “town squares” lined with storefronts designed to look as if they weren’t built all at once and rented out to chains like Restoration Hardware and Starbucks. Developers hire jugglers to simulate a “vibrant street life,” and everyone wears khakis ordered from the Lands’ End catalog and talks endlessly about their kids’ sports teams.

This sort of thing feels vaguely insulting when Brooks is describing the subculture you belong to, but the payoff is that you get to smirk meanly when he’s nailing, say, the $6 ice cream cone purchasers of the “Professional Zone,” with their debates about “the merits and demerits of Corian countertops” and their streets where “there are so many blue New York Times delivery bags in the driveways … they are visible from space.” The meanness lies in knowing that every American wants to think that his or her lifestyle is a reflection of individual taste, and that the more affluent the person, the more dearly held is the delusion of originality. “You,” says Woody Allen’s Alvy Singer in “Annie Hall,” to a character played by Carol Kane, “you’re like New York, Jewish, left-wing, liberal, intellectual, Central Park West, Brandeis University, the socialist summer camps and the father with the Ben Shahn drawings, strike-oriented, red diaper … ” “I love being reduced to a cultural stereotype,” she responds sarcastically.

This technique only works if it’s deadly accurate, and recently Sasha Issenberg of Philadelphia Magazine caused a minor media furor when he was able to demonstrate that some of Brooks’ claims about lower-middle-class neighborhoods in his area were wrong. He’s not alone. I don’t personally know much about Manhattan’s ultrahip nightlife, but even I am aware that “rich and beautiful supermodels” don’t “stand around in bars trying to look like Sylvia Plath and the Methadone Sisters.” (Sylvia Plath may have been suicidal, but she always looked like the well-groomed, twin-set-clad Smith graduate she was, and supermodels haven’t tried to resemble heroin addicts for years.) The kind of bohemians who talk “knowledgeably about Cuban film festivals” and “lament the spread of McDonald’s and Disney and the threat of American cultural imperialism” do not frequent Ian Schrager hotels.

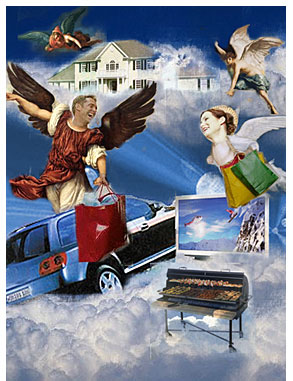

But this is mere pettifoggery. Brooks’ cachet comes not from mocking metropolitan hipsters but from lecturing them on the fundamental goodness of the people of Exurbia, those Americans he christens, Adam-and-Eve style, as Patio Man and Realtor Mom. Granted, there’s some gentle teasing about the monstrous size of their SUVs and their visits to megastore centers where “the parking lot is so big you could set off a nuclear device in the center and nobody would notice in the stores on either end.” There’s a line about how “in America it is acceptable to cut off any driver in a vehicle that costs a third more than yours. That’s called democracy.”

Ultimately, though, Brooks cherishes these people. They epitomize something precious in and essential to our national character, our “energy and mobility and dreams of ascent.” Unlike the residents of Bike-Messenger Land or the Crunchy Suburbs, they don’t pretend to reject the American hankering for achievement and wealth while guiltily succumbing to it. They straightforwardly pursue their own dreams of paradise.

Brooks’ expertise when it comes to exurbia is itself notably friction-free. Patio Man and Realtor Mom are paper dolls, composites of statistical information, like the digital inhabitants of SimCity. Unable to speak in their own voices (the book features no interviews with exurbanites), they express their inner Middle American virtue via their favorite brands, their aversion to traffic and the neatness of their lawns. It turns out that the source of Brooks’ knowledge about them comes mostly from reading magazines like American Demographics and hanging out at big-box malls with a 3-by-5 memo pad. “On Paradise Drive” is crammed higgledy-piggledy with statistics, informing you here that “blacks spend more on poultry and telephones and less on furniture and books,” and there that “a quarter of all women have considered breast-augmentation surgery.”

Like a lot of demographic information, the data that Brooks uses is generated mostly by market research firms. And this, at heart, is why the cultural portraits in “On Paradise Drive” feel so thin. Market research firms only care about what people buy, or to be more precise, the aspects of people’s lives that determine what they buy. By hanging out at Wal-Mart taking notes or by culling trade magazines for tidbits like the three things homebuyers most want (more counter space, basement space and closet space), Brooks endorses these parameters. After all, his own reputation is built on sharp little sketches of various cultural types based almost entirely on the products they consume. As far as Brooks is concerned, you are what you buy.

That characterization probably wouldn’t trouble Brooks much, because the thesis behind “On Paradise Drive” is that Americans “are driven to realize grand and utopian ideals through material things.” It’s not that foreign and homegrown critics are wrong in pegging Americans as venal, it’s that they’re blind to the ways that we use venal things like whirlpool baths and Jeep Grand Cherokees to express our longing for transcendence. Home Depot and the PowerPoint presentation you put together to succeed at the business you start in order to shop there are both manifestations of “a spiritual impulse that is quite impressive and profound.”

Since Brooks has spent the entire book, and much of his career, lampooning all the values we think we manifest through the stuff we own, this is a weirdly sanguine assertion. His point seems to be that the hope with which people chase their dreams of affluence somehow ennobles their goals: “The redeeming fact about American business life is that it is a stimulant. It calls forth boundless energy.” Brooks envisions legions of would-be entrepreneurs, filing through what even he describes as the “sheer existential nothingness of an office-park lobby” in search of the one little idea they can promote into a fortune. (His ur-example is Ray Kroc’s French fry, on which the empire of McDonald’s was founded.) “The quest may be epic, but the goal is trivial,” he writes. In other words, the means justifies the end.

And the end is shopping. Brooks assures us that, contrary to the theories of all those old, bearded, spoilsport social thinkers from centuries past, who claimed that people buy expensive stuff to lord it over their neighbors, American love to shop because they’re just so imaginative. You see, even when they can’t afford a Tiffany bracelet or a Lexus, they linger over the pages of glossy consumer magazines luxuriating in daydreams about the perfect future in which they might have it all. After diverting portraits of three such magazines (Real Simple, Easyriders and Cigar Aficionado), in all their pretension and vulgarity, Brooks suddenly veers into praise for the perpetual cycle of longing they inspire. It is not pathetic and misguided, he insists. It is “a realm of enchantment, anticipation and ecstasy.”

Did you know that “often the pleasure that shoppers get from anticipating an object is greater than the pleasure they get from owning it”? In fact, no sooner do they get it than they start fantasizing about how great their lives will finally be once they buy something else. Glossy magazines fuel this hunger because they are fantabulous dream factories, convincing us to aspire to the splendor of $1,400 cigars and to believe that “the cash register is a gateway to paradise.” Brooks adds that all this is not “entirely benign.” Really? You think? “Still, shoppers are bathed in hope. The products they confront might be trivial baubles or shams, but shoppers get caught up in the romance and spend optimistically, if not wisely.”

Brooks may see this as an “impulse to utopia,” but to me it looks a whole lot like what Marx called “commodity fetishism,” a useful term for the aura of glamour advertising spins around some object in order to convince you to pay much more for it than it’s actually worth. Marketing convinces you that the purchase will satisfy some inchoate longing and when it fails to do so, you keep coming back for more junk, hoping against all common sense that this time it will do the trick. How can anyone not see this? I mean, we’re going back to Sociology 101, here.

Since Brooks believes in marketing the way other people believe in the Bible or, for that matter, in Marx, he can somehow envision the whole circus as a beneficent gift to the American people, rather than a sleazy racket. It doesn’t seem to occur to him that there is a terrible waste in all that American ingenuity going to collecting more and more crap, that we might spend so much money and watch so much TV and eat so much junk food because we are bored, and we are bored because we are unchallenged, and we are unchallenged because we have been sidetracked by easy, pleasant piffle. “People who look at advertisements want to want,” he writes. “They are not passive victims in these fantasies.” This may be true, but people want candy, cocaine and cigarettes, too, and that doesn’t make them good for us.

I’m placing Brooks’ argument in the silliest possible light, granted, but it’s not much of a reach to get it there. To be fair, “On Paradise Drive” is not completely specious. Brooks is right that there is something invigorating and life-affirming about the idealistic, can-do spirit of American society, hokey as it may sound. And any spiritual or philosophical system that doesn’t allow for the pleasures of the physical world is impoverished and inhuman. But so is any system that doesn’t account for the suffering and loss inherent to life on earth, and Brooks’ sun-drenched vision of the ever-burgeoning American utopia is just such a system. (Even if he does offer a few demurrals about our willingness to sacrifice safety — i.e., social welfare — for opportunity — i.e., minimal taxes and government regulation.)

“Hopeful American dreamers, who have their heads filled with visions of their own future glories, are never going to develop the tragic view of life that is supposed to be the prerequisite for the probing and profound soul,” Brooks writes. Maybe, but to paraphrase a proverb from Alcoholics Anonymous (a quintessential American institution), you don’t have to worry about getting in touch with tragedy, because sooner or later, tragedy will get in touch with you.

The categorical opposite of Brooks’ outlook was elegantly expressed by Graham Greene, in his novel “The Quiet American.” Brooks has read it, but clearly it hasn’t sunk in, because in “On Paradise Drive” he describes Alden Pyle, the idealistic CIA agent hell-bent on installing democracy in Vietnam, who leaves a swath of catastrophe and carnage in his wake, as the novel’s “protagonist.” The book’s actual hero is Thomas Fowler, a broken Englishman, a journalist, who knows just how dangerous Pyle’s simple, arrogant optimism will be. Fowler is a man with the tragic view of life, and eventually, if briefly, Pyle catches up with him. Even Americans aren’t immune to tragedy, a lesson that, apparently, we have to learn over and over again.