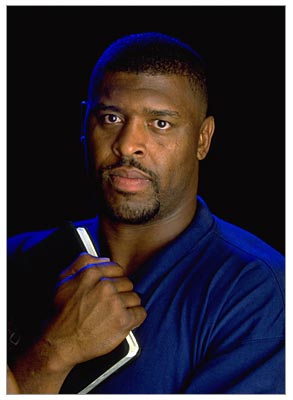

When I interviewed pro football veteran Troy Vincent last spring for my research on religion in sports, I asked how he accounted for the rise of Christianity in the National Football League (a cause that the Pro Bowl cornerback Vincent has helped advance). Vincent was quick with his answer: Reggie White. A whole constellation of factors has gone into the growth of faith in the game over the past two decades, but Vincent was certainly right in the sense that White, “the Minister of Defense,” brought new legitimacy to the now prevalent practice of Christian sports stars using their status as a soapbox from which they evangelize. Never before had a Christian player combined such on-field achievement — White was selected to the Pro Bowl a record 13 times — with such outspoken proclamations of faith and unabashed proselytizing.

That is why it is so interesting, and in my view important, to pay attention to the dramatically different stance on religion that White developed after his playing career, which came to public attention just before his death on Dec. 26. Since his retirement from the NFL in 2000, White had disavowed his role as the exemplar of athletic evangelizing and much of what passes for religious devotion in sports culture.

In an interview aired on the NFL Network four days before his death — part of an hour-long program on religion in pro football — White talked about his new direction. The man who once claimed that God told him to leave Philadelphia and sign with Green Bay, stated, “Sometimes when I look back on my life, there are a lot of things I said God said. I realize he didn’t say nothing. It was what Reggie wanted to do. I do feel the Father … gave me some signals … but you won’t hear me anymore saying God spoke to me about something — unless I read something in scripture and I know.”

In the interview, White also rejected a practice at the very heart of the athletic Christian movement, one he did much to popularize: the perceived imperative for the star athlete to use his stature to spread the Christian message. That was one of the founding goals of the Fellowship of Christian Athletes when it formed a half century ago, and it remains a major thrust of athletic Christianity today, acted out every time a player points to the heavens after a touchdown or home run, credits Jesus in an interview, or puts his fame to work in front of church congregations and youth gatherings. “I was an entertainer,” White said. “People seemed to want to be entertained rather than taught.”

I don’t doubt the sincerity of players who express their faith. But fans should not overlook the reality that a Christian network of considerable breadth, depth and influence operates behind the scenes to convert players and to enlist them in an effort to sway others who play and follow sports. Through the work of a variety of evangelical ministries, all on the conservative side of the social and religious spectrum, nearly every one of the teams in the three major professional sports leagues — football, basketball, baseball — has an officially designated chaplain. By some estimates as many as 40 percent of the players in the NFL participate in team chapels and Bible studies.

White’s point about entertaining elucidates one of the problems with Christianity in professional sports: a tendency of the movement to place promotion over the full and accurate representation of scripture and to use athletes as high-profile pitchmen, as if religious faith were just another product to sell. White actually had a credential; he was an ordained minister, although admittedly not one who was well versed in scripture. But most sports stars who stand before congregations or the media’s cameras and microphones are even less qualified than White, and they often do a poor job of representing Christianity, whether by word or deed.

The most common and notorious misrepresentation is that religious players frequently credit the Almighty for their making the big play or winning the game, as if the Christian (and non-Christian) players on the opposing team did not enjoy equal standing before God, and as if the purpose of faith is to get ahead on the scoreboard. Equally troubling is the frequent dissonance between players’ religious words and decidedly irreligious behavior. Barry Bonds is a serial sky-pointer and a man who credits God for his tremendous success on the field, yet to many in the public he is considered a steroid-using cheater. The football player recently fined $75,000 for the vicious hit on Green Bay Packers receiver Robert Ferguson is the same Donovin Darius who appears in the NFL Network program declaring his commitment to use his football playing to glorify God.

“Folk theology” is how two leading scholars of the Christianity-in-sports movement describe the athletic-flavored religion served up by sports stars. In their 1999 book, “Muscular Christianity: Evangelical Protestants and the Development of American Sport,” Tony Ladd and James A. Mathisen take the movement to task for a lack of biblical soundness born of an overemphasis on promotion. The authors write that “muscular Christian heroes” reduce orthodox Christian teaching to “SportsWorld rhetoric.” Their critique could hardly be dismissed for anti-Christian bias; Ladd and Mathisen are on the faculty of Wheaton College, a Christian institution in Illinois and a leading center of evangelical thought.

Events of 2004 dramatically highlighted the extent to which Christianity has taken hold in professional sports. Dwight Howard, the No. 1 pick in this year’s NBA draft, is a deeply religious young man who publicly declared his intention to Christianize the NBA and one day see a cross on the league’s logo. The biggest sports story of the year, of course, was the Boston Red Sox and their faith-drenched run to baseball’s world championship, with Curt Schilling telling a national television audience that the Lord enabled him to pitch despite his injured, bloody ankle, and Pedro Martinez declaring that God powered Boston’s first World Series title since 1918. “I don’t believe in curses,” Martinez told the newspapers after the team’s sweep of St. Louis. “I just believe in God, and he was the one who helped us.”

In his time, White spoke regularly at churches and often used post-game interviews as opportunities to proclaim Jesus. He even proselytized to those he was beating on the field; he was known to warn opposing linemen, “Jesus coming, I hope you’re ready,” before proceeding to demolish them on his way to the quarterback.

But in the NFL Network interview, the retired, more contemplative White said he felt “prostituted” by those who encouraged him to capitalize on his football fame to promote religion. It is hard to imagine a more blunt and damning repudiation than what White issued.

“Really, in many respects I’ve been prostituted. Most people who wanted me to speak at their churches only asked me to speak because I played football, not because I was this great religious guy or this theologian … I got caught up in some of that until I got older and I got sick of it.

“I’ve been a preacher for 21 years, preaching what somebody wrote or what I heard somebody else say. I was not a student of scripture. I came to the realization I’d become more of a motivational speaker than a teacher of the word.”

Don’t give White too much blame or credit for the state of faith in the game. (And to be sure, credit is due. There is little doubt that Christianity has influenced countless athletes to lead more moral, selfless lives than they otherwise might.) Although he was certainly a leader, White was also a product of a movement far bigger than he, one that remains deeply embedded in professional sports.

But as we know now, White was no longer part of that movement at the time of his death. “Maybe I was wrong,” he said in the recent interview. “I used to have people tell me, ‘God has given you the ability to play football so you could tell the world about him.’ Well, he doesn’t need football to let the world know about him. When you look at the scriptures, you’ll see that most of the prophets weren’t popular guys. I came to the realization that what God needed from me more than anything is a way of living instead of the things I was saying. Now I know I’ve got to sit down and get it right.”

The retired White was repentant about his infamous address before the Wisconsin State Assembly in 1998. ESPN’s Andrea Kremer reports that White told her in a recent, as-yet-unaired interview that he regretted the disparaging stereotypes he had made about various ethnic groups. But it was not clear from Kremer’s reports whether White felt repentant about the ugly anti-gay remarks he had included in the ill-informed address. In the immediate aftermath of the speech, White had been somewhat apologetic about the ethnic remarks. But he stubbornly refused to back away from his blatant homophobia. Had his recent journey led him to a more enlightened position on homosexuality? Given White’s record on the issue, it’s hard to give him the benefit of the doubt.

Still, toward the last part of his life, White was doing something astonishing for a man who used to hate reading: He was learning Hebrew with the aim of studying the Old Testament in its original language. “I came to the realization,” he said, “that if I’m going to find God, I’d better find him for myself.”

White’s new direction was apparently not well received by all who knew him. He said some Christians found his study of Hebrew objectionable and his searching attitude heretical. Some ministers, he said, warned other Christians to stay away from him.

I think they would do well to emulate him. The retired Minister of Defense was on an admirable quest to “get it right,” to wrest a deeper understanding of Christianity back from a culture of jock religion that too often trivializes faith in its zeal to promote it. As White apparently came to realize, little justice is done to the Christian religion by players chattering on camera about “God’s blessing” or by sports heroes who hit the evangelical circuit without the necessary theological equipment.

Reggie White was on a promising path. It is tragic that death blocked him just as he was getting started.