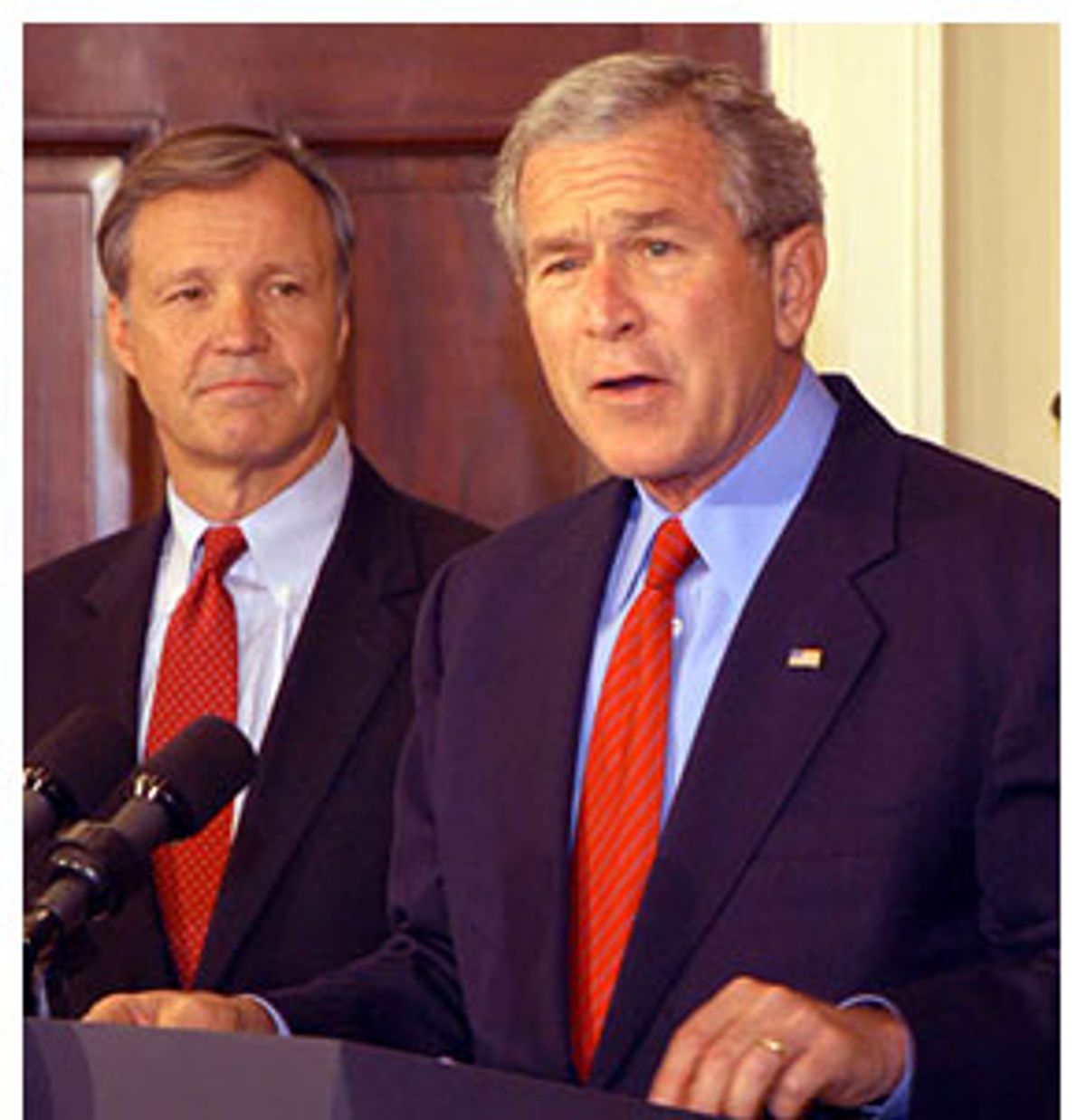

When President Bush announced Rep. Chris Cox, R-Calif., as his nominee to chair the Securities and Exchange Commission last month, he said Cox would work to "guarantee honesty and transparency in our markets and corporate boardrooms." It was an odd choice of words, considering that Cox's signature achievement during his 17 years in Congress is the enactment of a law, the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995, that by all accounts has made it more difficult for corporate executives who lie to investors to be held responsible for their actions. According to experts, this law played a significant role in bringing about the spate of fraud cases at WorldCom, Enron and numerous other corporations in recent years.

Although Senate hearings have not yet been held on Cox's nomination, corporations are already anticipating the changes he would be likely to make in their favor, considering his pro-corporate stance in the past. Corporate lobbyists are "almost giddy at the prospect of Cox" being put in charge of market regulation as SEC chairman, Business Week recently reported. If confirmed, Cox would be in a position not only to dial back enforcement of investor-friendly laws like the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 but also put the brakes on initiatives set into motion by former SEC chairman William Donaldson (who stepped down June 30), such as requiring corporations to treat stock options as an expense and mutual fund companies to have independent board members.

Co-sponsored by Cox and Sen. Chris Dodd, D-Conn., the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act was a central plank of the Republicans' "Contract With America," and was ostensibly aimed at discouraging frivolous lawsuits by investors. But the law provides considerable legal protections for corporate executives -- and, just as important, their accountants and lawyers -- who mislead investors. For example, the law provides a "safe harbor" for executives who make inaccurate "forward-looking statements" about their company's future prospects. Securities lawyers refer to this provision as "the license to lie."

Under the PSLRA (which became law over President Clinton's veto), before a court can even accept a corporate fraud case, investors must prove there is a "strong inference" that the corporate defendant acted with the specific intent to "deceive, manipulate or defraud." This is a very tough standard to meet. The 7th Circuit Court of Appeals, interpreting the PSLRA, dismissed fraud cases against corporate executives who said they simply forgot to disclose damaging information to investors. (Cox favored an even more severe version of the law that would have shielded corporations from lawsuits in nearly every circumstance.)

But describing Cox as a principal author of the bill doesn't do justice to his significant role in its enactment. Cox was a PSLRA evangelist, and he sought to demonize his opposition. During a congressional hearing on the bill on Jan. 19, 1995, Cox described lawsuits by investors for securities fraud as "a scandal of corruption on a scale Congress hasn't witnessed since the days of Eliot Ness and Al Capone." These lawsuits, in Cox's view, were nothing more than an "extortion racket."

One of the witnesses at the hearing, echoing Cox's theme, claimed he was "intimidated and threatened" by Rep. Ed Markey, D-Mass., and securities lawyer Bill Lerach (who also testified) for agreeing to appear at the hearing. The witness, AES Corp. president Dennis Bakke, later admitted under questioning by former Rep. Jack Fields, R-Texas, that no one had threatened him; he apologized and said he was referring to advisors who warned him about retribution. Cox was undeterred. When it was his turn to question Bakke, he said, "You pass on to those advisors, whoever they were, that they weren't altogether wrong."

Lerach, whom Cox described as earning his living through "legalized extortion," turned out to be particularly prescient about the impact of the law. In his opening statement at the hearing, Lerach said that if the PSLRA was enacted, "in 10 or 15 years you will be holding another hearing with the debacle in the securities market that will make you remember the [savings and loan] mess with fondness -- because the fraudsters and the dishonest people are there, and if the prohibitions against fraud are removed, they will come forward [and] they will become more active."

As it turns out, Lerach was overly optimistic. Corporate fraud began to wreak havoc on the nation's economy just five years later, not only at WorldCom and Enron but at Cendant, Sunbeam, Livent, Waste Management and Rite Aid, among others. Congress held hearings to find out what had gone wrong. In December 2001, testifying before the Senate about the Enron bankruptcy, Columbia University law professor John Coffee Jr., a noted expert in securities law, cited four separate provisions of the PSLRA as contributing factors in the epidemic.

Cox, for his part, has never wavered from his pro-corporate stance. In response to criticism that the PSLRA would help Enron executives defend themselves, he told the National Review Online in February 2002 that the law "is a very healthy and happy thing amidst this veil [sic] of tears." He has also clumsily attempted to argue that the PSLRA has actually protected investors. For example, in 2002 Cox said the law "requires a company and its officers to constantly update and correct any forward-looking statement once made." But according to the official Congressional Research Service summary, the law "states that there is no duty upon any person to update a forward-looking statement."

Cox's evangelism about the law isn't terribly surprising. He has admitted that his approach to securities law is intensely personal. For much of the time that he was pushing the PSLRA through Congress, he was being sued for securities fraud. Cox conceded to the New York Times in 1995 that being the target of securities fraud litigation had caused him to "sympathize with people who are victimized in these suits."

Cox's trouble started while he was practicing as an attorney for the firm of Latham & Watkins in the mid-'80s. In 1985, Cox wrote a letter on behalf of a client, First Pension Corp., to California securities regulators, assuring them that a new investment scheme dreamed up by First Pension CEO William Cooper was "low risk" and designed to be "fair, just and equitable" to investors. (Cox left out of the letter that Cooper was then under investigation by the SEC and had had his real-estate license suspended in connection with fraud at another company.) In fact, the investment Cox touted was a scam that defrauded small investors out of $130 million. Los Angeles Times columnist Michael Hiltzik described it as "one of the most flagrant con schemes in Orange County history."

Just one week before the PSLRA bill was introduced, attorneys representing First Pension investors were threatening to add Cox as a defendant in their suit. The Associated Press noted that although the PSLRA would not directly affect the First Pension case because it was filed in state court, "it could affect future legal actions brought in federal court against him or his former law firm, Latham & Watkins." But despite the apparent conflict of interest, Cox continued advocating for the bill, even after he was formally added as a defendant.

Spokespersons for Cox are quick to point out that Cox was eventually dropped as a defendant. But according to Michael Aguirre, who represented several hundred First Pension investors in the case, Latham & Watkins bailed out Cox. Aguirre, who is now San Diego's city attorney, told the Los Angeles Times "that in return for dropping Cox from the case he secured an agreement that Cox's actions could be imputed to Latham [& Watkins] in assessing its legal liability." Aguirre eventually reached a settlement with Latham & Watkins; the terms are secret. Cooper and a couple of his associates went to prison.

In 2002, after the economy was shaken by a wave of corporate fraud, Congress reversed the deregulatory path favored by Cox and passed the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, which was designed to keep corporate fraud in check, just as investor lawsuits had done before the PSLRA became law. The new law provided more accountability for corporate executives, more disclosure of financial information and more independence for corporate auditors. But the business community was highly critical of how SEC chairman Donaldson implemented the law. U.S. Chamber of Commerce president William Donahue described Sarbanes-Oxley as a "runaway system of corporate destruction being run by ... the people who work at the SEC." Corporations are now counting on Cox to turn back the clock at the SEC.

Hearings on Cox's nomination are expected to occur sometime before Congress' August recess. Thus far, with Congress preoccupied with Supreme Court retirements, John Bolton and whether Karl Rove will be criminally indicted, there has been little vocal opposition to Cox among elected officials. (One of the Senate's most liberal members, California Democrat Barbara Boxer, has indicated she will introduce Cox at his Senate banking committee hearing as a show of support.) But should the Senate banking committee conduct an aggressive investigation of Cox -- perhaps subpoenaing William Cooper and the confidential settlement with Latham & Watkins -- his nomination could grow contentious quickly.

Shares