The last two stories I read by Octavia E. Butler prior to her death in February, at the age of 58, were "The Book of Martha" and "Amnesty." Both were published in 2003, and both are available in the SciFi.com archives. Neither, in my opinion, is absolutely first-rate Butler; still, they are quintessential as to theme and character. They have their own strengths, and remind you of the pure stuff that made Butler's work so powerful.

The opening to "The Book of Martha" makes for sad rereading now, though. In it, God tells Martha that she is free for the very first time. Martha seems to be much like a younger Butler -- a woman of 43, an African-American and a writer. Her first concern is that she must be dead, and she doesn't want to be. Her last memories of earth are of writing, the "sweet frenzy of creation that she lived for."

As it turns out, Martha is not dead; God merely has a task for her. The human race is racing toward self-destruction and the black, female science fiction writer is being given the chance to save the world. The rules of this deal-with-the-deity story are as follows: Martha can make a single change and whatever society results, she must occupy the bottom rung of it. "I don't believe in utopias," Martha tells God, and no reader of the fiction of Octavia Butler could doubt this.

In the second story, "Amnesty," a woman named Noah works as translator between humans and a species of alien invader referred to as the Communities. The arrival of the Communities has crashed the economy; humans are dependent now on the aliens for employment and food. Many humans died in the days of early contact -- the aliens experimented casually on them to discover what the human body could and could not withstand. The humans have not forgiven this.

The Communities ask Noah to turn six human recruits into willing workers. Abducted by the aliens at age 11, released only many years later, Noah knows, as the recruits do not, that the Communities can and will completely eliminate humans if the two species prove unable to live together. No one has asked, but Noah has taken on herself the task of saving humankind. She has no reason to love either side. When the Communities finally released her, she was seized and tortured by the military for information she was assumed to be withholding. Much worse, she tells the recruits, to be tortured by your own, who know what they're doing, who know how to hurt you, than by the curious, ignorant aliens.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

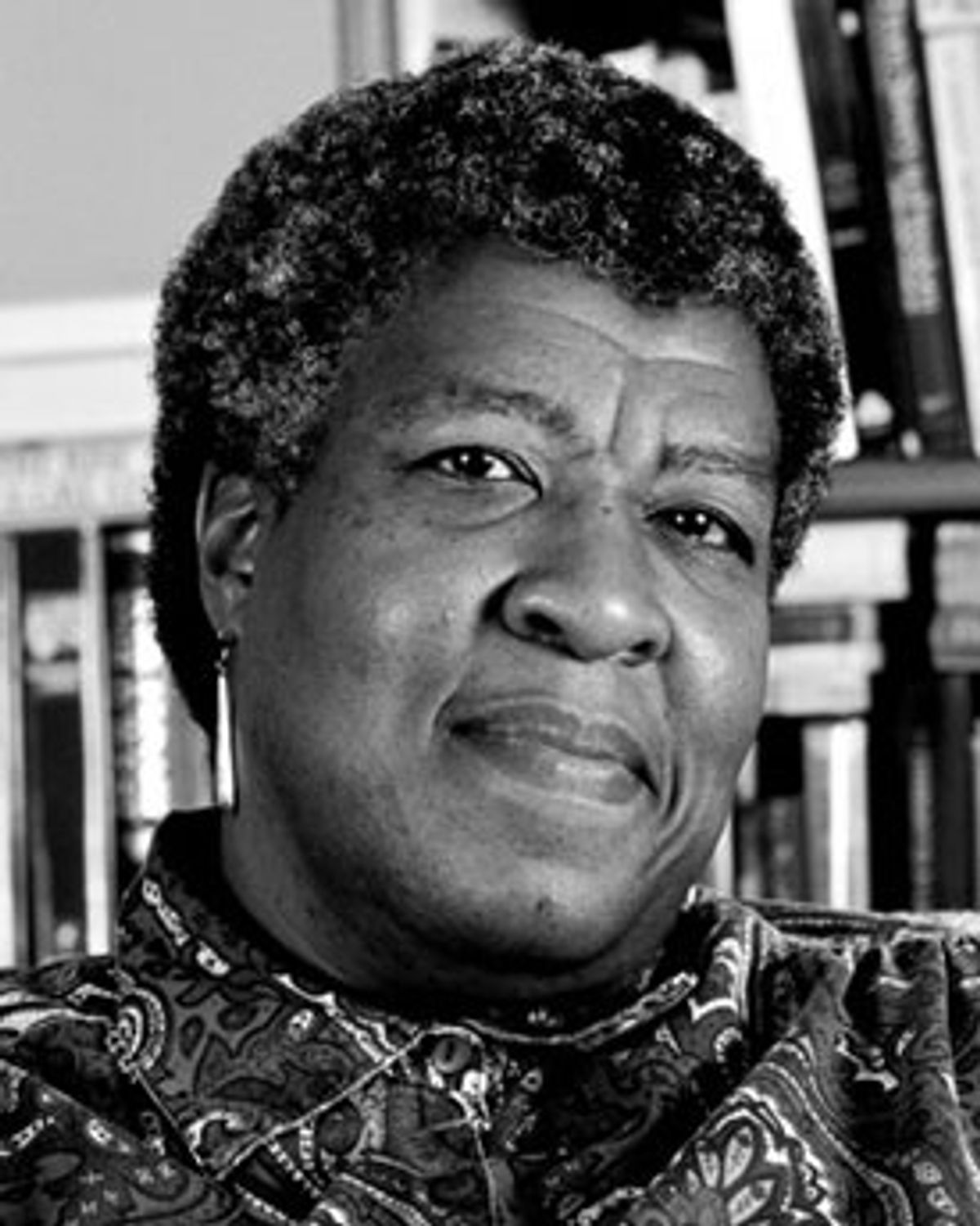

Octavia Butler often described herself as an outsider, but within science fiction she was loved as an insider, someone who was a fan first and came to s.f. writing as an enthusiastic reader. She said many times in many interviews that she began to write science fiction at age 12, having seen the movie "Devil Girl From Mars" and been convinced that she could tell a better story than that. (Her first published novel, "Patternmaster" in 1976, was purportedly a reworking of her childhood story.) As a young woman she attended the Clarion Science Fiction Writers Workshop, at which she later taught many times, and in the 1980s won both the Hugo and Nebula awards for short work. In 1995, when she received a MacArthur "genius" grant, the reaction inside the field was one of pride and pleasure for one of our own.

She also described herself as a hermit, but on the occasions when I met her she struck me less as reclusive than as shy. She had the wrong body for someone who so disliked being conspicuous -- she was extremely tall and imposing -- and the wrong personality for someone in the public eye. In 1985 when she won the Nebula, her acceptance speech consisted of a thank you and the observation that she had become a writer "in order to avoid moments like this." Yet she was, through sheer determination, an effective, seemingly confident public speaker. Formal and impressive onstage, she was warm and friendly in person. She used to say that the last thing she wanted was for her work to be prophetic. In 1993 when she wrote "Parable of the Sower" -- which is, among other things, a meditation on the ways a nation can turn to fascism, an evergreen issue in George W. Bush's America -- she was not trying to predict but to warn.

I learned of Butler's death (too young, with too much work left to do) through a phone call while it was still a rumor. Moments later, confirmation appeared online on various science fiction Web sites. A science fiction convention known as Potlatch had convened that same weekend in Seattle, where Butler lived. She was expected to put in an appearance; there were plans for lunch. Her sudden death, the result of a fall in her front yard, was a terrible shock to everyone.

Octavia Butler was more interested in writing a good story than in worrying about where to slot it. She called herself a writer rather than a science fiction writer and said on at least one occasion, in an interview: "How dull it is to have people defining you." But she used scientific extrapolation in most of her work and did so carefully -- acknowledging what was known to be true and inventing only into the blank spaces on the map.

In the '70s and '80s, when much of the field was out in the clean, sterile sweep of space or jacking into the Web and leaving the body entirely, Butler's scientific interest was in biology. Her work is all about the body -- about disease, about reproduction, about the horrible realities of the food chain. Many of her stories feature graphic depictions of fluid-spilling, flesh-eating, oozing, gooey physicality. There were times as a reader when you might find yourself wishing her imagination and her prose were a little less vivid. In my opinion, she was one of the field's scariest writers. There was nowhere she wasn't willing to go in her imagination. There was nowhere she wasn't willing to take you.

She had a particular fascination with relationships of dominance and submission, master and slave, predator and prey. Though she always positioned herself on the side of the victims, she frequently focused on complicity, portraying such interactions as complicated and intimate. One cannot be eaten or raped without being touched. There was sometimes a narcotized pleasure built in on one side of the relationship or both. The idea of humans as carriers for alien seed, of cross-breeding between humans and aliens, of the mutual dependence of predator and prey -- these are staples of Butler's books, appearing in both her Patternist series (four novels) and her Xenogenesis trilogy. In some ways, her 1984 short story "Bloodchild" has distilled this to a disturbing essence.

"Bloodchild" takes place in a world where the dominant species, an insectlike alien called the Tlic, reproduces by laying an egg in a living host. When the larvae hatch, they eat their way out. Humans prove to be excellent hosts for Tlic larvae: In fact they provide the only possible means of reproduction; without the human hosts, the Tlic face extinction.

Initially the Tlic kept humans like animals just for this purpose, but it has become possible to intervene in the hatching so as to save the human host -- not always, but often. Over generations, families of Tlic and families of humans have become intertwined in an intimate sexual history. Gan, the human boy who is the protagonist of "Bloodchild," is not only the proposed host for the child of T'Gatoi, a highly placed Tlic, but also her brother, as his own father was host to her. T'Gatoi could compel Gan's cooperation, but she won't. The decision to bear T'Gatoi's child, or not, is left to Gan.

"Bloodchild" won both the Hugo and Nebula awards in 1985. A number of readers have argued that it's a story about slavery. Although this is a possible reading, it's a difficult one, and I can't help wondering how much it depends on knowing that the author of the work is a black woman. The slavery metaphor is contradicted, or at the very least complicated, by the consensual, loving relationship at the heart of the story.

Other readers have argued that "Bloodchild" is simply a gender reversal story in which the female impregnates the male and the male delivers, in great pain and at bodily risk, the baby. The egg-laying scene is subtly, uncomfortably erotic. Butler herself described it as a love story. The intimate relationship of predator and prey is the juice of the vampire tradition, and after a long struggle with writer's block, Butler arrived here (though science fictionalized) in her final novel, "Fledgling." Her vampire, who looks like a young girl, is in fact a 53-year-old member of a long-lived race that cohabits the world with humans, but predates them by many centuries. This race is called the Ina. Like vampires, the Ina need human blood to survive, but their feeding is not homicidal and the blood comes from willing volunteers. Maybe they're volunteers. Or maybe they're addicts. We learn that the saliva of the Ina carries a powerful addictive narcotic as well as an agent that extends the human's life. The book takes place in a fictional world and features a fictional race but is, once again, primarily about complicated, disturbing, tangled webs of dominance and submission, sex and compulsion.

Butler's novel "Kindred" may be the book most widely read by readers outside science fiction; it has been assigned as a text in classrooms and has sold steadily since its publication in 1979. Butler always refused to classify "Kindred" as science fiction, because there was no science in it, calling it instead "a grim fantasy." Still, it's clearly embedded in that science fictional tradition of stories that revolve around the conundrum of traveling back in time and killing your own grandfather.

Part of the impulse to write this book, Butler said, was guilt. Her own mother was taken out of school at the age of 10 and worked in jobs that, as a child, Butler found demeaning. It took her several years to see that endurance and sacrifice are, in fact, the characteristics of the hero.

The protagonist of "Kindred" is a modern woman from Southern California, a black woman married to a white man. She finds herself transported back to the pre-Civil War South, where she faces many terrible choices, including the quandary of whether to save the life of a sadistic slaver who is one of her own ancestors and, therefore, someone on whom her own future depends. About "Kindred," Butler said that she wanted people to think about what it would be like to have all of society arrayed against you. She wanted people to think about this often.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Last week, Dave Itzkoff, the new science fiction reviewer for the New York Times, created a stir on s.f. chat lists and blogs when he posted the titles of his 10 favorite books of science fiction. Since this list was never represented as more than an idiosyncratic selection of personal favorites, it's probably unfair to object. People must be allowed to like the books they like (however clear it is that the books we like are superior books) and I think (at least I think I think) it's better, even for reviewers, to be honest instead of politic about what they like.

And yet, with Butler's death still quite recent, quite raw, readers couldn't help noticing that the list is, among other things equally shocking but less to the point here, exclusively white, straight and male -- as the field of science fiction is not. If the New York Times ever asked the women of science fiction for our idiosyncratic, personal favorites, our lists would look quite different from Itzkoff's. No doubt they would also look quite different from each other's. Still, I think there are few among us who would not have included Octavia Butler in our top 10.

Shares