Ariel Manto, the heroine of "The End of Mr. Y," Scarlett Thomas' new novel, is an isolated grad student in an unnamed British university town. She has no money; an unheated, mouse-ridden apartment; an active but degrading sex life and a thesis advisor who has disappeared. "People who don't say I look intimidating sometimes say I look 'dodgy' or 'odd,'" she explains with some mystification. "One of my ex-housemates said he wouldn't like to be stuck on a desert island with me but didn't say why."

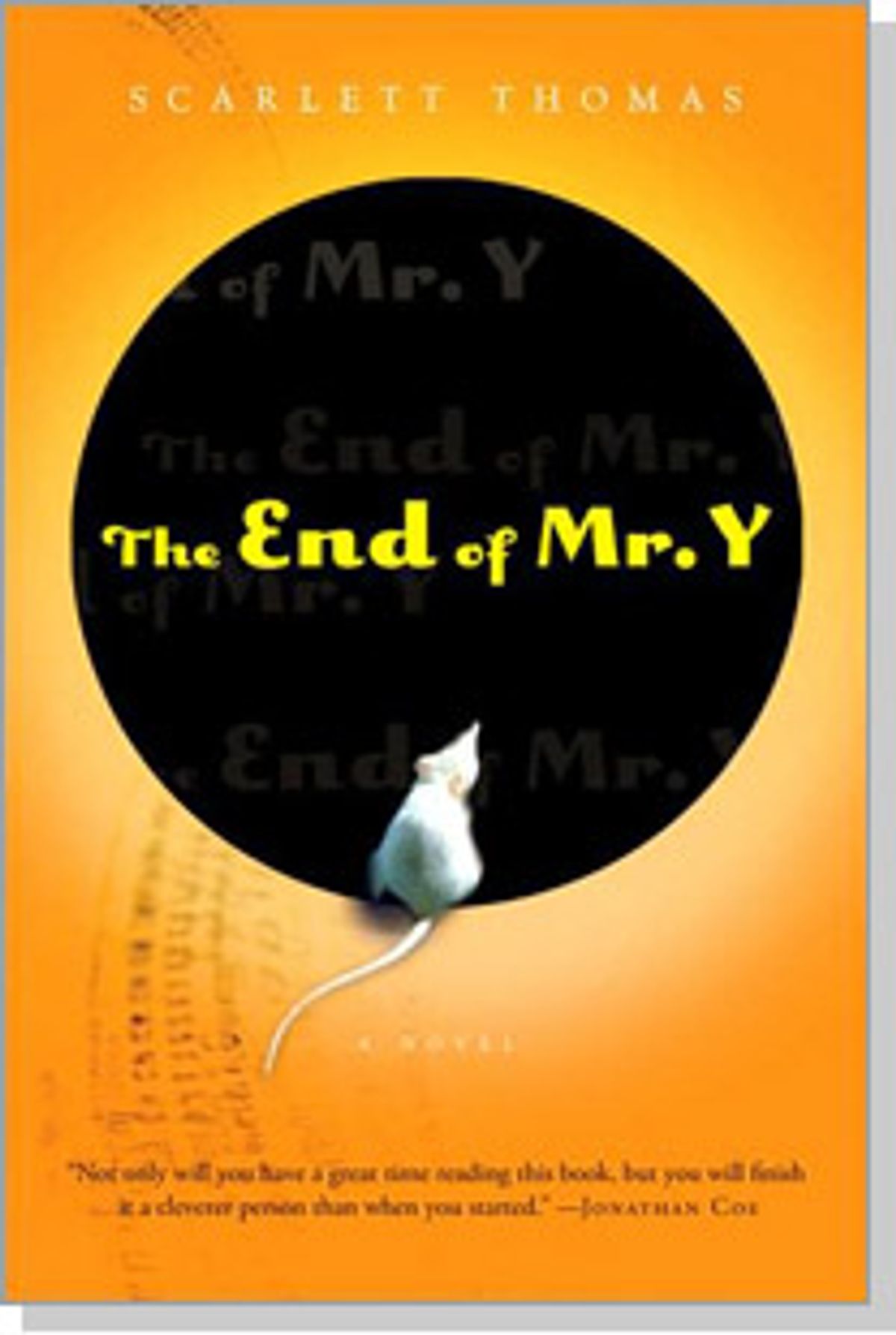

Depending on what kind of reader you are, Ariel might seem like such an intriguing narrator you won't even need to hear the additional bait: This is a story about a cursed book. But don't suppose that either of these setups offers a reliable forecast of what else you'll find in the pages of "The End of Mr. Y." Perhaps the most pleasing thing about this book is that just when you think it's settling in to be one kind of novel, it saunters off in another direction entirely.

Ariel, who is writing her thesis on 19th-century thought experiments, has a special interest in an obscure writer of the period named Thomas E. Lumas. The fictional Lumas was best known (when known at all) for punching Charles Darwin in the face ("he favored the evolutionary biologist Lamarck"). His final work of fiction, written after a long period of seclusion and crankery, was published the day before its author perished -- and after almost everyone else significantly associated with the book died, too. The only known copy of the novel (which is also called "The End of Mr. Y") lies locked in a German bank vault. No one that Ariel has ever heard of has ever read it -- it has the reputation of killing anyone who does. So when she finds a copy, in an unfamiliar bookstore she visits purely by accident, she empties her meager bank account to acquire it.

So far, this might sound like a cozily old-fashioned bibliophilic suspense yarn, along the lines of last year's creaky thriller "The Thirteenth Tale." But sharp-eyed readers will spot a line in an early paragraph that's a tip o' the hat to the famous first sentence of William Gibson's "Neuromancer," and guess that Thomas intends to take her readers to some very strange places indeed. In his preface to the cursed book, Lumas feverishly insists that it be considered "only as fiction," but this "novel" is patently autobiographical, and it contains instructions that turn out to be anything but fictional.

Following those instructions launches Ariel on a series of adventures that I will not describe overmuch here. She will have to scour homeopathic shops and hide out in churches from men in suits. She will find favor with the god of mice. She will almost trade sex for money, but avoid it by extraordinary, if not downright supernatural means. She will fall in love with an agnostic theology student. And perhaps most remarkable of all, she will find a practical use for her extensive knowledge of the post-structuralist theory of Jacques Derrida.

Although Ariel is researching a Victorian novelist, her interests are less literary than philosophical. (She almost decides to go back to school to study theoretical physics, which she thinks she can get through without needing too much math.) The epigraphs introducing the book's three parts come from the likes of Heidegger, Jean Beaudrillard, Aristotle and the 19th-century novelist of ideas who seems a likely model for Lumas, Samuel Butler. "The End of Mr. Y" (Thomas' version, that is) is literary manna for would-be philosophy nerds, people who liked "Sophie's World" but wished the fictional parts were more grown-up. It's the kind of book where someone can say "Whoops... I forgot all about phenomenology there and almost became an empiricist," and raise a wry chuckle from the other characters present.

Yet unlike other intellectually driven fiction -- that, say, of Umberto Eco -- which can bog down in its own cerebral excesses, "The End of Mr. Y" never loses touch with the fact that it's a novel. There are little, 100-percent-literary sugar plums to be found in its pages, like the summaries Ariel offers of Lumas' short stories, making him sound like an alluring precursor to Borges; in one, two philosophers try in vain to leave a blue room, and in another an exact but impenetrable copy of a man's house appears across the street from his real house. Above all, "The End of Mr. Y" is always the story of a fairly screwed-up girl trying to become a somewhat less screwed-up girl (and to avoid being killed by government agents, when it comes to that). This keeps its feet firmly planted on earth, however much the ground rumbles beneath them.

Shares