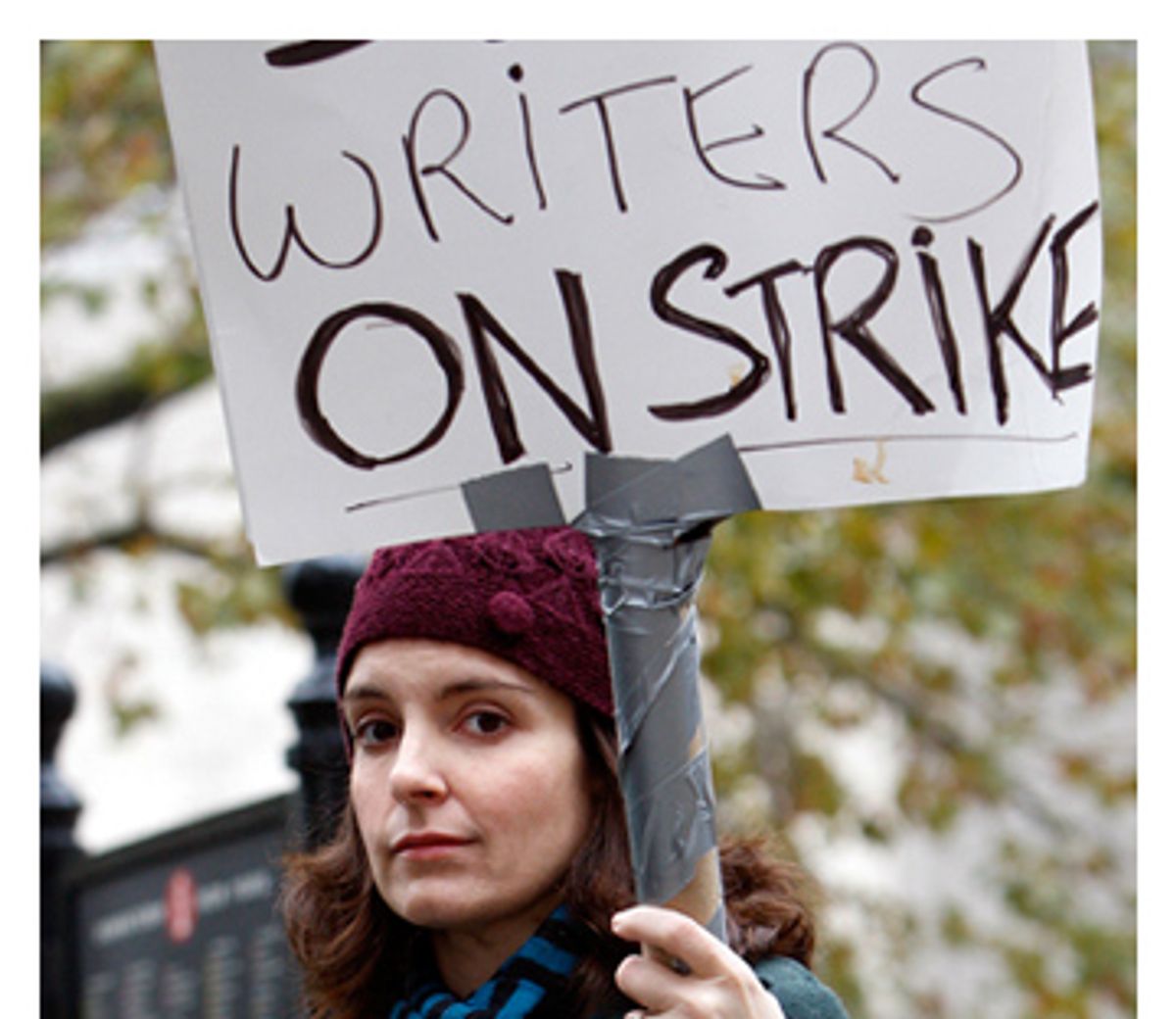

As a member of the Writers Guild of America, I have walked the picket lines in front of the Time Warner Center and other media headquarters in New York over the past few weeks, contributing my feet and my voice to the strike that is currently paralyzing the entertainment industry. By any standard, I'm low on the industry totem pole, so I couldn't help feeling a deep sense of excitement as I shared the sidewalk -- and the shadow of an inflatable rat -- with Tina Fey, Tim Robbins, Holly Hunter, Oliver Platt, Seth Myers, Sam Waterston and the many other celebrities who marched in solidarity.

Most causes benefit from the presence of a major star: Michael J. Fox turned his Parkinson's diagnosis into political and financial action in the search for a cure. Cancer survivor Lance Armstrong's six Tour de France victories have inspired the purchase of millions of tiny yellow "Livestrong" wristbands and generated millions more in financial contributions to his foundation.

For the WGA, though, too much star power might actually be a bad thing. As the strike drags on, an entertainment-starved audience might soon turn on Hollywood. Scripted television will give way to nonstop reality TV, viewers will run out of backlogged episodes of "Grey's Anatomy" on their TiVos -- and try telling a "Lost" fan that the show now might not come back until 2009. Will anyone have any sympathy for a bunch of millionaire writers then?

As the Guild is quick to point out, at any time 50 percent of its members are unemployed. In New York, where union-sanctioned shows are limited to late-night comedy, soap operas, the news and the various "Law & Order" series, it sometimes feels as if that number is higher. The fact is that most of the Guild's members are not millionaire writers. Some of us are "Who Wants to Be a Millionaire" writers.

From 1999 to 2003 I was a member of the staff of the hit ABC game show, one of approximately 13 writers developing questions, jokes, promotions and other material related to the Regis Philbin-helmed phenomenon. When the series debuted, it quickly generated millions of dollars for ABC, and it didn't take a Magic 8-Ball to predict that other networks would soon try to duplicate its success. "Millionaire" begat "Greed," and "Greed" begat "The Weakest Link," and "The Weakest Link" begat "Deal or No Deal," and "Deal or No Deal" begat "Power of Ten," itself produced by Michael Davies, who brought "Millionaire" to U.S. television sets in the first place. Imitation, as the saying goes, is the sincerest form of television.

Recognizing the change that "Millionaire" would bring to the television landscape, the WGA was eager to fold the show's writers into the union, and we were eager to join. Although it might seem silly to complain about a job spent writing "What sound does a dog make?" and other gems, before we joined the WGA we frequently argued with the producers over vacation days, hours and the amount and type of work expected from each writer. Writing questions for the show seemed clear enough, but what about other material? "Millionaire" launched an online game, and it needed as many questions as dozens of episodes of the show. It seems quaint now, but in 1999 the idea of a television show having an online, interactive component was uncharted territory. Where did television writing stop and promotional writing begin?

Then the WGA stepped in. Writers were very clearly divided into those who wrote for the show and those who wrote "ancillary" material, such as CD-ROMs, online games and promotional tie-ins. We were signed to fixed-length, renewable contracts at salaries that increased at predetermined amounts from season to season, eliminating the fear we all had that we might come into work one day to find that our jobs had been outsourced to trivia writers in Bangalore. We also received health insurance, a brass ring so far out of reach of most people in creative professions that they often don't exercise or leave the house for fear of getting injured.

Eventually, "Millionaire's" success began to wane, a victim of overprogramming and the insatiable desire of TV audiences to always watch the next cultural juggernaut. As questions piled up in the show's database like grains of corn in a silo during a bumper crop year, there was less of a need to have the same number of writers poring over encyclopedias and surfing the Internet for new trivia. A switch from prime time to daytime and syndication meant that the show commanded fewer advertising dollars, and season by season the producers figured out how to produce the show for less money and with fewer staff members. I was let go in December 2003.

If ever there was a time when I valued my WGA membership the most, it was when I wasn't working. Thanks to the Guild's qualification policy, I had earned enough during my time at "Millionaire" to keep my health insurance for another year. When that ran out, I held onto the WGA's excellent coverage by making COBRA payments. That ends next month, almost four years to the day after I wrote my last trivia question.

With the competition for television writing jobs fierce and the likelihood of extended unemployment high, the most important benefit of my experience with "Millionaire" came in the form of residuals, which supplemented my paltry income for nearly two years after my time in the hot seat was up. When reruns aired I would receive a check a month or two later for as little as $25 or as much as a few hundred dollars.

Even though I haven't had a WGA-covered job since I worked at "Millionaire," I will continue to join the picket line until the strike is resolved. Why?

As long as "Millionaire" can still make money for its producers, then it should still make money for me and my fellow writers. Like any TV show, there is a set formula for how much money each writer receives for reruns on network and cable television. But for some reason that logic is not extended to new media, and no clear formula exists for the Internet. (Actually, a formula does exist: Take the number of episodes streamed or downloaded online, add the amount of money generated by advertising, and then multiply that number by zero.)

One could argue that I was merely a cog in the machine, an overpaid monkey at an iMac, churning out word after word until something suitable for broadcast came together. And besides, I couldn't argue with anyone who pointed out that I didn't originate the concept for the show. But a television program's premise is not the only factor contributing to its success. After all, boil down any series to its most basic elements and even the biggest hits might not sound very entertaining. A show about nothing? A bunch of co-workers at a paper company? Bored housewives living in suburbia? Who cares? It's the content of individual episodes that makes the show -- and that makes money -- whether those involved were there at the creation or not.

ABC and the show's producers will make a lot of money for a long time from the work I did alongside my fellow writers at "Who Wants to Be a Millionaire." The same holds true across the industry. Whether they produce new shows or dig deep into their libraries, there is no show that networks, studios and production companies won't be able to monetize in the form of webisodes, online games, cellphone ringtones, downloads and other digital media. I've read "The Long Tail." One day that million-dollar question I wrote or the joke I put in Regis' mouth will be streamed online, preceded by a 30-second ad that will generate money for someone. Just not me.

"What was the first movie to be featured as a promotional tie in with the McDonald's Happy Meal?"* -- your choices are "Star Wars," "Superman: The Movie," "Star Trek: The Motion Picture" or "Raiders of the Lost Ark" -- is not likely to make it into Bartlett's next to "Here's looking at you, kid," but it didn't exist anywhere on network television until I wrote it.

*The answer: "Star Trek: The Motion Picture."

Shares