After years of hanging out with cops, Richard Price has developed uncanny powers of mimicry and observation when it comes to the lives of small-time criminals. Only the novelist George Pelecanos, a fellow screenwriter for “The Wire,” and their mentor, Elmore Leonard, are his rivals, and I doubt even they hear as many kinds of crazy music in American speech as Price does. Most of his books and screenplays since “Clockers” seem driven by a wish to glorify the endlessly creative ways English is pulverized and recast in the mouths of black and Latino teenagers and white law enforcement. He is as enamored of police bureaucratese (of shorthand terms like “vics” and “eye-wits”) as he is of raunchy slang. I pity his foreign-language translators.

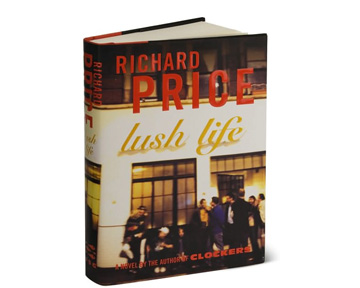

“Lush Life,” Price’s latest tour of down-low urban America, is another astonishing performance and his most acute study so far of the Darwinian adaptations required to survive in our city jungles. His New York City cops have evolved special ears and eyes to detect criminals in their environment. Mention the word “upstate” and they won’t think of vacations in the Finger Lakes. Rather, they’re already figuring out which prison, state or federal. In their minds, a driver who signals lane changes and goes under the speed limit on the Lower East Side is begging to be pulled over by the Quality of Life Task Force. Only someone with drugs or a gun under the seat obeys all the traffic laws in this neighborhood.

You’re guilty until proven innocent in the Fifth Precinct, where everyone is some kind of sinner and the pressure from higher-ups is intense on detectives to clear messy crimes off the books, whatever the evidence.

That’s how Eric Cash, the 34-year-old bartender at Café Berkmann and a would-be screenwriter, ends up in jail as a murder suspect. He and a guy he barely knows from the restaurant are walking the guy’s drunken friend home at 4 a.m. when the trio is held up by two young armed thugs from the nearby projects. Asked to turn over their wallets, Eric’s co-worker decides to resist and is fatally shot. (The victim’s dying words to the gunman, “Not tonight, my man,” are later played up as heroic by the New York tabloids, one of several times that “Lush Life” awkwardly emulates the satiric scope of “Bonfire of the Vanities.”)

When eyewitnesses claim for various self-serving reasons that they never saw the two criminals, just the trio of white guys, Eric finds himself grilled by the two detectives assigned to the case, Matty and Yolanda. They relentlessly ask him to describe what happened that night, probing each of his sleep-deprived versions for the tiniest inconsistencies. That they can’t find a motive or the gun doesn’t matter. If you’ve ever wondered how people could confess to a crime they didn’t commit, read the agonizing but nonviolent 75-page interrogation scene in “Lush Life” and wonder no more.

The book is a first-rate police procedural. We know who pulled the trigger. The suspense comes from finding out whether he will be caught, and how, and what other casualties will ensue. Matty and Yolanda have to spend almost as much effort tending to the victim’s father, unhinged by his son’s death, as they do to running down leads on the killer.

Inner-city streets are, in Price’s view, the stage for a play that often ends as tragedy but is at its base a farce:

“Just as Big Dap said, ‘What the fuck I tell you about that shit?’ to Little Dap, who was putting the finishing touches on a laundry-marker dick in the ear of the soldier on the bus-shelter recruiting poster, the corner of Oliver and St. James became awash in the fluttering light atop the Quality of Life taxi: both Daps and everyone else automatically and forbearingly turning their eyes skyward as if posing for a religious painting.”

But Price’s mimetic gifts and wide-ranging empathies have begun to hamper him as a novelist. Perhaps he has been writing too many scripts, because “Lush Life” is more a collection of brilliantly realistic scenes than a book with moral weight or a convincing vision of the way New York functions in the Bloomberg era. The sections read as if they could just as easily have been a series of one-act plays or television episodes. Too much of the plot is rendered in vivid dialogue that could better have been narrated, streamlined or elided altogether.

What we should think about the gentrification of the Lower East Side, where Price lived in the ’70s, is never clear either. Eric, presumably the author’s stand-in, is plagued with self-loathing, no career prospects, and a fickle girlfriend who has left him to research the sex trade in the Philippines. After being brutalized by both the cops and local drug dealers, the mixologist has every reason to hate the city and escape upstate. Why he stays seems to have more to do with the author’s sentimental attachment to the place than the character’s.

Price is as much a member of the law-abiding bourgeoisie as his many readers. But you’d never know from this book that he, with an MFA from Columbia, belonged to the first wave of Lower East Side gentrifiers or “La Bohemers,” as he calls them here. When one of the few college graduates in “Lush Life” begins to speechify on gun control and poverty in the liberal tones of a New York Times editorial, the words sound so foreign and pompous to Eric’s ears as to be genuinely offensive. Price seems so fond of streetwise impudence and cynicism that middle-class hypocrisy and cant become in some ways a less forgivable crime than murder.

There isn’t a page of “Lush Life” that doesn’t offer something to smile at or savor. The book tunnels underground and brings to light a New York few of us ever see, from disintegrating Orthodox temples to Chinatown boardinghouses where men rent out boards to other tenants. A few of them keep a carp that has grown so large it can no longer turn around in its fish tank, a perfect and terrifying image of the conditions in which many New Yorkers live.

Every scabrous exchange of dialogue here has an authentic texture. But pieced together, they form a synthetic whole, much like the re-creation of the Lower East Side in Atlantic City that is the book’s unpersuasive conclusion and what passes for its unifying conceit and social statement. The only customers who might be eager to visit such a place are the yuppies for whom Price seems to harbor a barely hidden contempt.

These final pages will probably look better on the screen than they read now in a book. Price is in constant demand from Hollywood and must have asked himself at several junctures whether he was writing a novel or a screenplay. I was unsure myself until the end, when Price pulls back from his tight focus on the history and color of the neighborhood where he misspent his youth. As Eric stares out at the Atlantic Ocean and throws away his cigarette, you can already hear the mournful trumpet on the soundtrack.