Perhaps the best key to the Barack Obama phenomenon (as opposed to Obama the man) is a book that never even mentions the Illinois senator: Rob Walker's "Buying In: The Secret Dialogue Between What We Buy and Who We Are." Observing the launch of Red Bull, an energy drink, Walker noted that instead of attempting to assert the brand's identity to a mass market, the manufacturer pursued a strategy of what he calls "murketing," sponsoring low-key events geared to distinct niches; ask any of these groups what Red Bull is and you're likely to hear a different answer. By refusing to define Red Bull, advertisers allowed each slice of its overall market to interpret the beverage for itself. Likewise, the "vagueness" that many flinty political junkies complain of in Obama permits all sorts of disparate people -- progressives, independents, intellectuals, young people, minority advocates, renegade Republicans -- to see the reflection of their own desires in the self-described "skinny kid with a funny name."

Obama the symbol possesses the enviable quality that Walker calls "projectability," and Obama himself has marveled that he often seems to be "a blank screen on which people of vastly different political stripes project their own views." He is, in short, a cutting-edge brand. But if he does win the general election, what then? A brand can't be president of the United States. Once in the Oval Office what beliefs, values and ideas would Obama bring to the job? Rather than look at calculated official pronouncements (a recent release cited William Shakespeare and Ernest Hemingway as the candidate's favorite authors) it's time to take a closer look at some of the formative books in his intellectual and political life to see if we can learn more about the man behind the movement.

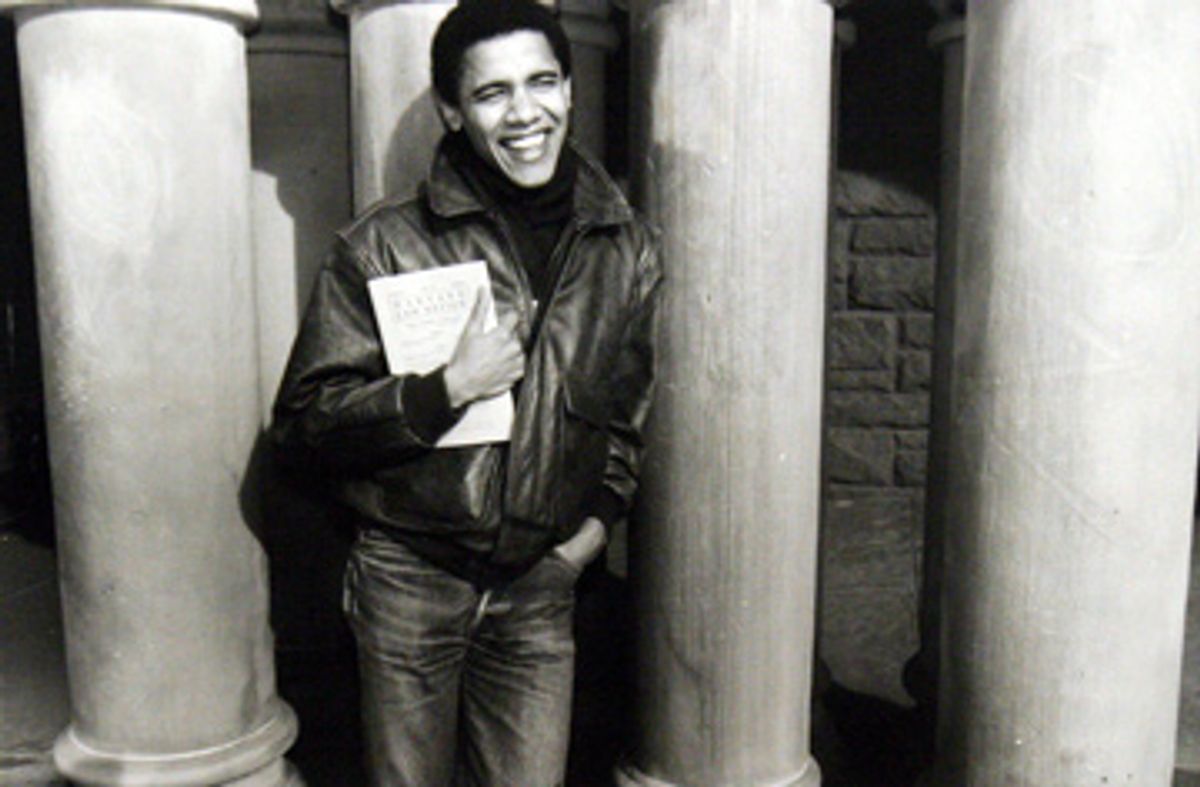

If Obama is elected, he'll be one of the most literary presidents in recent memory. Although his boyhood and youth in Hawaii and Indonesia were not especially bookish, Obama the reader blossomed as an undergraduate at Occidental College in California and, especially, during the two monkish years he spent finishing up his degree at Columbia University in New York. "I had tons of books," he told his biographer, David Mendell ("Obama: From Promise to Power"), about this time in his life. "I read everything. I think that was the period when I grew as much as I have ever grown intellectually. But it was a very internal growth." Even after he left New York to work as a community organizer in Chicago, Mendell reports, Obama lived so much like a retiring writer -- spending many hours holed up in a spartan apartment with volumes of "philosophy and literature" -- that some of his colleagues assumed he was gathering material for a novel.

A taste for serious fiction is rare in the American male these days, but Obama has it. According to several friends, he even tried his hand at writing short stories during those early years in Chicago, and he recalls priggishly scolding his half sister, Maya, while she was visiting him in New York, because she chose to watch TV instead of reading some novels he'd given her. Among the authors he favored during his years of intensive reading were Herman Melville, Toni Morrison and E.L. Doctorow (cited as his favorite before he switched to Shakespeare). He has also mentioned Philip Roth, whose struggles to shrug off the strictures of Jewish American community leaders must have resonated with the young activist.

The biracial Obama, invested with a sense of his African-American heritage by his idealistic white mother, but largely raised (by her parents) among whites, found himself questioning the social and political ideas of the educated blacks he met after moving to the U.S. mainland. His memoir, "Dreams From My Father," is framed as a quest, the story of a young man's journey toward an African-American identity that felt authentic and vital, yet didn't demand that he reject his white family and friends.

Although Obama has mentioned Ralph Ellison only in passing, it's difficult not to see "Dreams From My Father" as a variation on Ellison's 1952 modernist classic, "Invisible Man." Ellison, too, felt hemmed in by the demands of community. The nameless narrator of that novel is thrust into a series of roles imposed on him by both white and black society, until he finally retreats from the world entirely. Obama's own story ends on a much more hopeful note, but as he considers and critiques post-colonial theory, black nationalism, buppiedom, Afrocentrism, tribalism and so on, his restless search for the truth echoes that of the Invisible Man. According to "Dreams From My Father," among the characters in African-American literature, the adolescent Obama felt closest to Malcolm X, whose discipline and "repeated acts of self-creation" impressed him. Yet, when Malcolm wrote of the desire to "expunge" the white blood in his veins, Obama "was left to wonder what else I would be severing if and when I left my mother and my grandparents on some uncharted border."

In Chicago, Obama worked for the Developing Communities Project, a church-based group following the grass-roots organizing principles laid out by Saul Alinsky. Alinsky, a Chicago native, famously organized the impoverished Back of the Yards neighborhood in the 1930s and trained several generations of organizers, including César Chávez, before publishing "Rules for Radicals: A Pragmatic Primer for Realistic Radicals" in 1971. (He died the following year.)

The best-known Alinsky-style organizing body around today is the nationwide Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now, or ACORN, which works on projects such as stemming predatory lending practices, passing living-wage legislation and negotiating with developers for affordable housing. Although Obama's boss at the time told the National Review that DCP was not an especially strict Alinsky-style operation and Obama never mentions Alinsky by name, he has read "Rules for Radicals," according to his campaign; it would be hard to find any thoughtful community organizer who hasn't. Hillary Clinton's senior honors thesis at Wellesley College was on "the Alinsky model," although after her husband's election to the presidency, his administration tried to keep it under wraps for fear that it would make her appear too much the firebrand.

If you haven't read "Rules for Radicals," it's not what you might expect. Written with a vigor and a panache that amply convey Alinsky's legendary charisma, it is less a primer than a concise, witty and iconoclastic manifesto crossed with a war manual à la Sun Tzu. Alinsky wrote it to correct what he viewed as the many fatal errors of the generation of activists produced by the 1960s, whom he regarded as too dogmatic, too self-righteous, too romantic, too idealistic, too infatuated with exotic ideas and too impatient. Stylistically, the model can only be Nietzsche; the book is full of breathtakingly provocative assertions and nifty aphorisms. "He who fears corruption fears life," Alinsky writes at one point. At another he attributes the naiveté of Machiavelli's views on morality to his lack of "experience as an active politician," and concludes that had the Italian been more worldly, he would have realized that morality and power are not disconnected. Instead, as Alinsky sees it, morality provides a noble-sounding excuse for actions that invariably arise out of self-interest.

Obama himself went through a period of "devouring" the work of Nietzsche while living in New York. It's difficult to say what Obama might have absorbed from the German philosopher, mostly because Nietzsche himself is so hard to pin down, but one of Obama's favorite instructors at Occidental told Mendell that anyone who immersed themselves in his thought would learn "to call everything into question." Steeped as he was in the history of the civil rights movement (Taylor Branch's history "Parting the Waters" was a seminal book at this time), he couldn't help noticing that some self-styled African-American activists were using the more extreme rhetoric of the '60s primarily to shore up their own power, or else were purists who "preferred the dream to the reality, impotence to compromise." In the 1980s, when Obama was organizing on Chicago's South Side, the pieties of '60s-era leftism -- from identity politics to the idea that, provided with the right social environment, people can be rendered peaceful, industrious and altruistic -- had become a kind of dogma. Alinsky's ruthless demolishing of these and other utopian illusions would have been even more bracing then than it was when "Rules for Radicals" was first published, at the height of the counterculture's idealism.

Bravado aside, the Alinsky model observes some basic rules, such as focusing on concrete, achievable goals, especially at first, so that a demoralized group can build up a sense of its own power. An important Alinsky maxim is "never go outside the experience of your people." This means (among other things) not insisting on reforming a neighborhood's retrograde attitudes on issues such as race, gender, class, capitalism and sexual orientation before you try to get the toxic-waste dump cleaned up.

In "Dreams From My Father," Obama recalls that the organizer who trained him told him to interview neighborhood residents in order to "find out their self-interest. That's why people become involved in organizing -- because they think they'll get something out of it. Once I found an issue enough people cared about, I could take them into action. With enough actions, I could start to build power. Issues, action, power, self-interest. I like these concepts. They bespoke a certain hardheadedness, a worldly lack of sentiment; politics, not religion."

Being willing to cut a deal with the enemy is part of a practical, hardheaded political strategy; as Alinsky wrote, "To the organizer, compromise is a key and beautiful word." An activist I know told me that the strength of the Alinsky-model groups is that "they get things done," but (as a recent arrangement ACORN made with developers in Brooklyn, N.Y., illustrates) they also leave themselves open to charges of selling out.

Despite the "radical" label that made the Clintons' image managers so nervous, Alinsky considered himself to be well within the boundaries of "Judeo-Christianity and the democratic political tradition." One book he invariably assigned to his students was Reinhold Niebuhr's "Moral Man and Immoral Society," and Obama has in turn described Niebuhr (to New York Times Op-Ed columnist David Brooks) as "one of my favorite philosophers." Martin Luther King Jr. and Jimmy Carter were inspired by the work of this 20th century German-American Protestant theologian, and so are some of the "theoconservative" apologists for the war in Iraq, as well as liberal hawks like Peter Beinert, former editor of the New Republic. So broad is Niebuhr's appeal that, as Paul Elie observed last year in an excellent essay on Niebuhr in the Atlantic Monthly, "a well-turned Niebuhr reference is the speechwriter's equivalent of a photo op with Bono."

"Moral Man and Immoral Society," published in 1932, represents the utmost left of the Niebuhrian spectrum; it even evinces some Marxist notions, such as the assumption that capitalism will eventually pass away, echoes of the time when Niebuhr campaigned for the state Senate in New York on the Socialist ticket. As a result of the Second World War, he abandoned the socialism and pacifism of his youth and became the founder of a school of thought known as Christian realism, which provided a theological justification -- grounded in original sin and the concept of a "fallen world" -- for the use of military power to enforce the greater good. This made him beloved of cold warriors. It is this "muscular" Christianity that the Iraq war's early proponents found so useful in arguing that the United States had a moral obligation to use its military might to fight evil abroad.

Critics of the war, however, can just as easily point out that Niebuhr cautioned humility in such matters. Deciding, as George W. Bush did, that America was the righteous agent of God's will on earth would not have sat well with Niebuhr. When Obama made his important 2002 speech at a rally opposing the invasion of Iraq, he said, "I don't oppose all wars. What I am opposed to is a dumb war. What I am opposed to is a rash war." Obama told Brooks that what he'd taken from Niebuhr is "the compelling idea that there's serious evil in the world, and hardship and pain. And we should be humble and modest in our belief we can eliminate those things. But we shouldn't use that as an excuse for cynicism and inaction. I take away ... the sense we have to make these efforts knowing they are hard, and not swinging from naive idealism to bitter realism."

Perhaps more relevant to Obama than Niebuhr's position on war was his lifelong mission to criticize liberalism from within. "Moral Man and Immoral Society" challenges the progressive creed of its time, the belief that society can be perfected, whether through the adoption of true Christian ethics or through reason and education (or, for that matter, through communism). The book is, in short, a brief against any notion of social engineering. Individuals can learn to be altruistic, Niebuhr allowed, but groups never will. Elites will always defend their power, and human beings have always chosen to "invent romantic and moral interpretations of the real facts, preferring to obscure rather than reveal the true character of their collective behavior." Furthermore, "political opinions are inevitably rooted in economic interests of some kind or other and only comparatively few citizens can view a problem of social policy without regard to their interest."

Alinsky was a self-described radical and Niebuhr was a devout Christian but neither man was an idealist. Both tended to see morality as a kind of cover story used by groups who, in Niebuhr's words, "take for themselves whatever their power can command." That doesn't mean that these two men believed that nobody had the ability or will to change the world for the better. However, anyone who attempts to do so better be ready to get his hands dirty. So when we turn to the book Obama has most recently cited as a major influence, Doris Kearns Goodwin's "Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln," it's not the Lincoln of popular American myth -- the secular saint and martyr -- we find praised there. It's Lincoln the wily politician, who was not above carefully hedging his public positions and who prided himself on cajoling his opponents to his side.

All presidential candidates would like to be seen as resembling Lincoln -- even those who aren't gangly master orators from Illinois. Obama is no exception; he announced his candidacy for president at the Old State Capitol building in Springfield, Ill., where, in 1858, Lincoln made his famous "House Divided" speech against slavery. Obama's own reputation-making speech at the 2004 Democratic Convention also called for national unity in the face of political polarization, even if the divide is not nearly so deep and the causes are considerably less grave.

Lincoln's path to the Emancipation Proclamation was far from direct and unwavering, as the few critics of Lincoln-olatry these days are wont to point out. As a state senator, Lincoln voted against a resolution declaring the "sacred ... right of property in slaves," but he didn't insist that Congress abolish slavery in the states where it was established, either. (He didn't believe that this was within the legislative body's legitimate powers.) In his 1858 debate with Stephen Douglas, he assured the audience that he was "not in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races."

Without a doubt, Lincoln abhorred slavery, but what Goodwin describes in "Team of Rivals" was not a fiery abolitionist but a politician who "rather than upbraid slave-owners ... sought to comprehend their position through empathy." He insisted that most of slavery's opponents would have supported it, too, if they had been born into the plantation economy and had a financial and cultural interest in perpetuating it. Similarly, in the early stages of his national career, Obama won praise for his ability to win over conservatives by listening respectfully to their demands and concerns. The premise of "Team of Rivals" is that Lincoln deftly incorporated his former opponents into his administration, winning them over with his prairie charm, formidable intellect and political acumen. The primary selling point of Obama's candidacy has been his promise to heal the bitter rift dividing red state from blue, left from right, black from white, just as Lincoln was able to persuade an assortment of men, formerly at one another's throats, to pull together to save the Union.

However, the rivals Lincoln incorporated into his administration were fellow Republicans. With the Democrats and the slave-holding states (all of which rejected him in the general election), there could be no compromise. American conservatives are not fools, and while a sympathetic ear and a considered reception of their ideas may turn down the temperature in the debates between left and right, sooner or later they will require something more substantial. Already, with his support of the FISA bill and death penalty, Obama has begun the predictable "shift toward the center" of every candidate moving from the primary to the general campaign.

Obama, whose color and youth signify "liberal" in the visual symbology of American politics, looks like that previously mythical creature -- a progressive capable of capturing enough votes to win the presidency. If he turns out, as is likely, to be far more middle of the road, some of his supporters will surely feel betrayed. But how justified will that sentiment be? Obama the reader and writer has already shown an affinity for pragmatism, whether it's the Cabinet-level maneuverings of Lincoln or the "Let's make a deal" activism of Alinsky or the "a man's gotta do what a man's gotta do" geopolitical realism of Niebuhr. Even in "The Audacity of Hope," a campaign bio (and therefore largely free of grist), he states:

"I think my party can be smug, detached and dogmatic at times. I believe in the free market, competition and entrepreneurship, and think no small number of government programs don't work as advertised ... I think America has more often been a force for good than for ill in the world; I carry few illusions about our enemies, and revere the courage and competence of our military. I reject a politics that is based solely on racial identity, gender identity, sexual orientation, or victimhood generally. I think much of what ails the inner city involves a breakdown in culture that will not be cured by money alone, and that our values and spiritual life matter at least as much as our GDP."

Unity sounds refreshing in a political culture battered and wearied by vicious partisanship. But bipartisanship means that sometimes the other side -- those people you've come to regard as the devil incarnate over the past 30 years -- will get what they want and you won't. Anyone who assumes that self-interest is what really motivates political groups isn't going to expect them to be moved by high-flown appeals to conscience and guilt; there will be wheeling, there will be dealing, and there will be half-measures. If he is elected, and if Obama asks his most idealistic champions to countenance some sacrifices, they will hardly be able to say that they weren't warned. Their disillusionment is most likely to come soon. Whether in the long run we'll regard him as a president who got things done or one who sold out will take a lot longer to decide.

Shares