When, back in October, a Northwest Airlines flight went AWOL over Minnesota, dropping out of radio contact and wandering off course, I had the same reaction as most people. What happened was shocking and unacceptable, I felt. It was embarrassing to pilots everywhere. Moreover, I had a difficult time imagining how two professional airmen could allow such a bizarre thing to happen. How was it even possible? The majority of my colleagues felt the same way.

The problem was, all we had to go on was the media's condensed presentation of the event: Two pilots, focused on their laptop computers, lost track of where they were and overshot their destination.

But was it really that simple?

Imagine, for a moment, the following scenario:

Flight 188 is en route from San Diego to Minneapolis, somewhere around Denver, when a flight attendant calls the cockpit to let the captain know his crew meal is ready. The captain takes his tray, and uses the opportunity to step out and use the lavatory.

While he is out of the cockpit, the first officer receives a call from air traffic control, asking him to contact the next sector on a new frequency. The instruction for the change sounds something like this: "Northwest 188, contact Denver Center now on 125.9."

The first officer acknowledges by repeating the information back to the controller, then setting the new frequency into one of the VHF radios.

"Good evening, Denver Center," he says next. "This is Northwest 188 with you, level at three-seven zero [37,000 feet]."

Radio frequencies are at least five digits long (often six digits overseas), and as you might expect, it's not unheard of for a pilot to accidentally transpose a couple of numbers. This happens from time to time and is seldom if ever dangerous. The situation is normally corrected after a minute or two, often because the incorrect frequency is completely silent: The crew gets no response, and there is no chatter from controllers or other pilots.

Aboard Flight 188, the first officer mixes up the numbers and dials in a frequency for Winnipeg, Canada, instead of Denver. Let's call this Factor 1.

Winnipeg is hundreds of miles away, and controllers there do not hear him. They are unable to acknowledge his call or correct his error. At the same time, however, Flight 188 is at a high enough altitude that transmissions from other aircraft under Winnipeg's control are clearly audible in the cockpit. Thus there is plenty of chatter coming over the radio. This leads the pilot to believe he is on the correct frequency. Let's call this Factor 2.

A short time later the captain returns. He too hears the radio chatter and has no reason to think anything is wrong. Factor 3.

When a pilot comes back from a restroom break, it is customary for the other pilot to brief him of any changes, such as a new altitude or heading assignment, revisions to the routing, radio frequency changes, and so forth. In this instance, nothing is said. The captain is not told of the frequency change, or about the fact that nobody acknowledged the first officer's call. This would be Factor 4.

Neither does the first officer, having received no reply, make a second attempt to contact ATC. Factor 5.

Why he neglects to do these things isn't clear, but neither is it shocking. After all, few things are more routine than dialing in a new radio frequency and, as we say, "checking in." This can happen dozens of time over the course of a flight, and failure to get a response from ATC on the first call is not uncommon, especially when a frequency is busy. Occasionally, when the chatter is unusually heavy, you wait for them to contact you. In addition, the first officer is distracted by the commotion and security rigmarole required when opening and closing the flight deck door. It's possible that he's simply forgotten. Factors 6, 7 and 8.

Soon thereafter, back on the correct frequency, Denver Center is trying to get hold of Flight 188, wondering why it never checked in. They call many times, to no avail. Minutes later, there is a shift change at the facility. For reasons unknown, the new controller is not told about the failure to reach Flight 188. Had he known about this, there are steps he could have taken to help track down the wayward flight. But he didn't. Factor 9.

As they fly along, unknowingly out of contact, the captain and first officer then get into a long discussion about the airline's new scheduling system for pilots. The first officer takes out his laptop and gives the captain a short tutorial on how to bid his monthly schedule. The captain takes his computer out as well. Neither computer is on for more than five minutes, but clearly both crew members are distracted. Factor 10.

On they fly, still out of contact with ATC. Worsening matters is a hundred-knot tailwind, and the fact that the pilots have their navigational screens set to the highest mileage range, which compresses the distances and waypoints and makes any deviation less noticeable. Factor 11.

At one point Northwest attempts to contact the plane via the on-board datalink system known as ACARS. On some aircraft, an incoming ACARS message is indicated by an audible chime. But on this one there is just a small light, and it stays illuminated for only 30 seconds. The message goes unnoticed. Factor 12.

Eventually a flight attendant calls on the interphone to ask about their arrival time. At this point the flight is directly over Minneapolis.

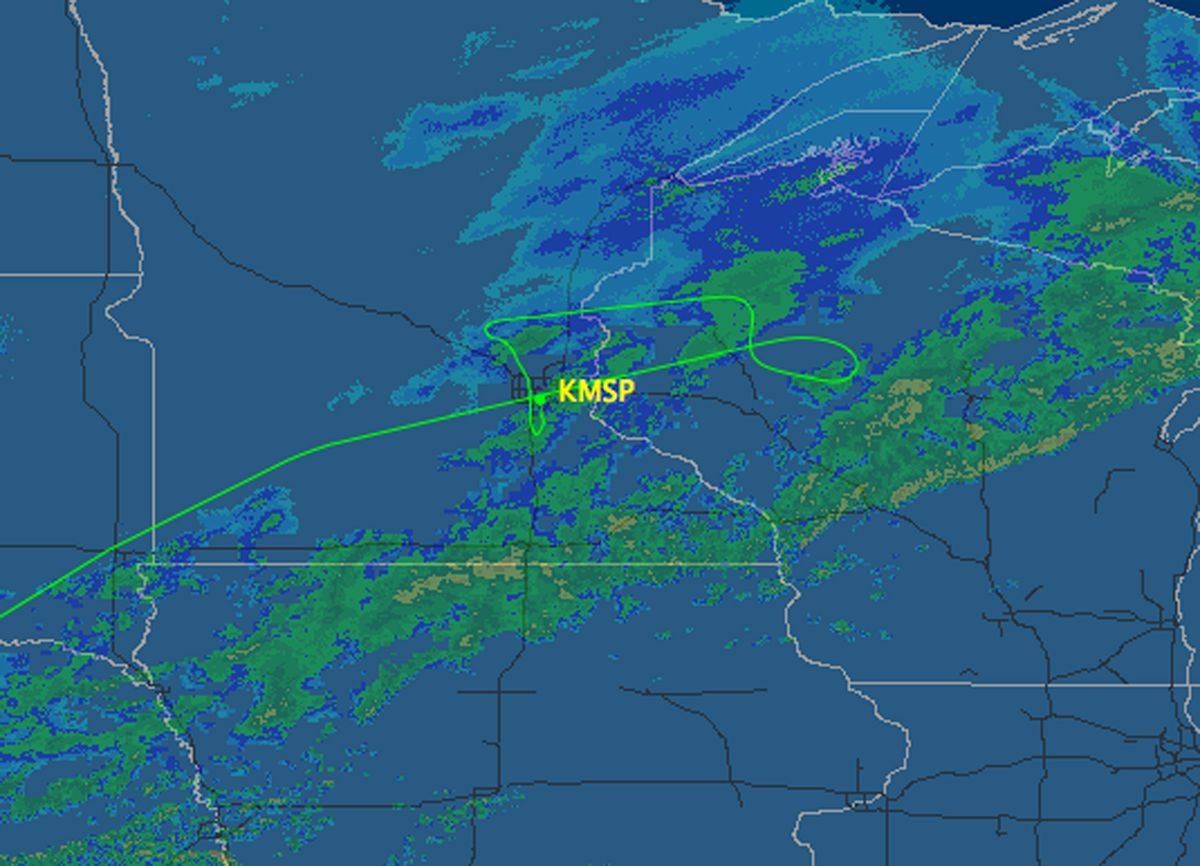

Depending on traffic, runway use, etc., arrival patterns can sometimes take a flight several miles beyond its destination before turning back again, but this is different. The crew realizes something is wrong. They track down a Minneapolis frequency, establish contact, and begin to receive instructions for landing. ATC is naturally suspicious, and puts the aircraft through a long series of turns to be certain the pilots haven't been hijacked and are in full control. Finally Flight 188 is cleared to land.

When the Airbus gets to the gate, the FAA and FBI are among those waiting.

And we all know the rest.

This scenario is based on a secondhand account written by a pilot who happens to be a friend of Flight 188's captain. The pilot's letter has been cited in news articles and blogs. I've paraphrased here and there, and rounded things out for clarity. I cannot know for certain if the details are accurate, but certainly they take what was, on the surface, a startling and borderline implausible story, and make it plausible.

In other words, laptops were only part of what went wrong. This was more than a pair of pilots zoning out under the glow of their computers. It was something less overt: a combination of small errors and oversights, not all of them of the crew's doing, creating a loss of what a pilot calls "situational awareness."

When it comes to aviation incidents, things are seldom as simple as they first seem, or as the media frames them. Here on Salon I have made my living emphasizing that point. I should pay more heed, maybe, to my own advice. I'm annoyed at myself for not being more suspicious of this incident from the start.

I'm just as annoyed that this story made such a splash in the first place and has spent so much time in the media spin cycle. It never deserved it. The airplane and its occupants were never in peril. The deviation occurred during the cruise portion of flight, with the aircraft plainly visible on ATC radar and in no danger of colliding with other aircraft or the ground. When it landed in Minneapolis, the jet still had two hours of fuel in its tanks and was only 15 minutes behind schedule, including a 35-minute delay out of San Diego.

The pilots are by no means off the hook. The entire mess could have been avoided had the frequency error been caught early on, as it should have been, and clearly both succumbed to a needless distraction. But do they deserve to be publicly excoriated and banned from ever again flying?

The pilots had their FAA certificates stripped through emergency revocation almost immediately, prior to any formal investigation. Reportedly, not everybody at the FAA thought this was the best of course of action, but pressure to do so came all the way from the White House. The media firestorm dictated that somebody had to be punished, and fast.

In summary, the saga of Flight 188 remains an embarrassing error. But not as scandalous an error, or as reckless an error, as it first appeared.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Which is all the more reason why our elected officials should back off and avoid pushing for federal legislation, as some have been doing, that would ban laptops and other devices from cockpits. Never mind that some carriers require pilots to carry laptops in the cockpit, for access to important charts and manuals; most of them already prohibit their recreational use. Is a federal law going to make any difference? Of all the things government could be doing to improve air safety, for any lawmaker to spend five minutes writing up legislation on computers is shameful.

As a general rule, anything a politician says or proposes about commercial air travel should be looked on with heavy skepticism. This isn't to say that every once in a while something intelligent and useful doesn't emerge from Washington.

Case in point: the Airline Safety and Pilot Training Improvement Act of 2009, passed by the House of Representatives earlier this fall. If voted into law, the measure will bring welcome changes to pilot training and hiring protocols. Not everyone is convinced the measure will pass the Senate, but it soared through the House by a vote of 409-11.

The legislation comes on the heels of last winter's Colgan disaster near Buffalo, N.Y. Fifty people were killed when the Dash-8 turboprop, operating as Continental Connection Flight 3407, fell on a house after stalling in bad weather. In addition to highlighting fatigue issues, the crash revealed the controversial hiring standards of many regional airlines.

The new law would require that pilots possess an FAA airline transport certificate (ATP) in order to be eligible for a cockpit job with any commercial carrier operating under Part 121 of the Federal Aviation Regulations -- that is, almost all of them. Requirements for an ATP include a minimum of 1,500 hours of flight time (broken down over various categories), and the satisfactory completion of a written test and in-flight examination. In recent years, regional airline new hires have been coming on board with as few as 250 total flight hours.

Additionally, the law will somewhat redefine the ATP certificate, with a focus on the operational environment of commercial air carriers, requiring specialized training in things like crew coordination, cockpit resource management and so on.

You'd take that for granted, but believe it or not, the existing ATP requires no specific training in airline procedures, and no prior experience in large aircraft or those requiring more than one pilot. One needs to pass a written exam and in-flight evaluation in a multi-engine aircraft, but you can obtain an "airline transport pilot" certificate having logged 1,500 hours flying Pipers and Cessnas.

The changes will make it easier to weed out those pilots who lack the acumen for airline operations. For those who progress, it will allow an easier transition from general aviation to the high-demand training environment at a regional. It will lower their training costs and, ultimately, make for safer cockpits.

As I've written before, logbook totals aren't always a good indicator of skill or performance, but it's hardly unreasonable to set the acceptance bar at or near the ATP standard. And in many ways this would represent a return to historical norms. In years past, the typical civilian new hire needed to accrue between 1,200 and 2,000 hours to be taken seriously by a regional airline.

(One concern I have is for those pilots already hired into cockpits with qualifications that don't meet the new standards, including many who are currently on furlough. Can they be called back to duty under the old rules? I presume they will be grandfathered in, which is only fair.)

For a would-be pilot, obtaining an ATP will entail a financial investment approaching or exceeding six figures. Theoretically, at least, this should encourage the regionals to begin offering better wages and benefits if they want to attract and retain experienced crews. For the time being, average first officer pay begins at around $20,000 a year. (I say "theoretically," because pilots have a terrible habit of, shall we say, suffering for their art.)

Rep. Jerry Costello, chairman of the House Aviation Subcommittee, calls the Airline Safety and Pilot Training Improvement Act "the strongest aviation safety bill since the creation of the FAA in 1958."

That's pretty strong, but on the whole I see something good for everybody: airlines, pilots and passengers alike.

Shares