Before you buy a knife, hold it. Think about its weight and balance and how comfortable it feels. A good knife is balanced, which makes it a little easier and less tiring to use. If you suspend the knife between thumb and forefinger, holding the top of the blade at its widest point next to the handle, the blade won’t tip much up or down. For ease and control, the best way to hold a chef’s knife is to grip the widest part of the blade itself between your thumb and curled forefinger, with three fingers firmly around the handle. You have the most leverage and again the most ease and control, if you cut with the wide part of the blade close to your hand.

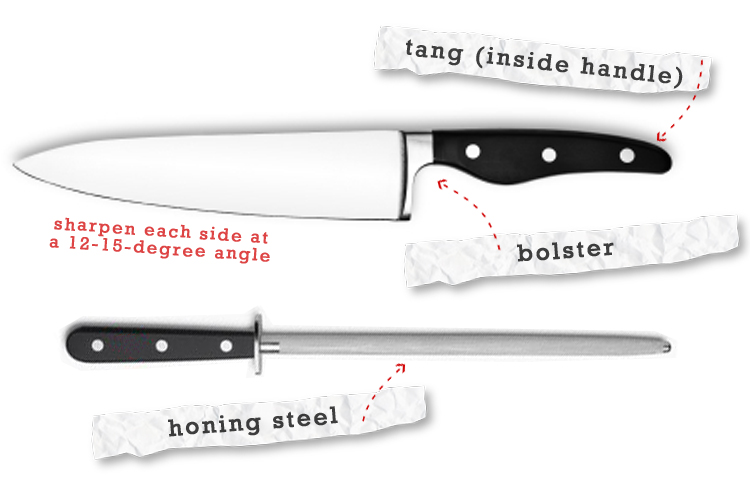

When you hold a good stamped knife this way, the handle should curve down to prevent your middle finger from uncomfortably pressing against the thin butt of the blade. On a forged knife, the side of your middle finger rests against the flat back of the bolster, an extra thickness of metal that reinforces the blade at the widest point and provides more to grasp. But a small bolster or none at all is better if you sharpen your own knives. As the blade is worn down slightly with each sharpening, the bolster, too, must be ground down now and then. Otherwise, it comes in contact with the cutting board, so the blade touches only at the bolster and the tip, not the middle, and you can’t cut all the way through food. Perhaps the biggest advantage to softer, old-fashioned staining steel blades (see part one of this article) is that the bolster is easier to reduce by hand. With stainless, which is so much harder, you almost have to use a grinding wheel.

The part of the blade that enters the handle is called the tang. A full tang is visible all around the edges of the handle, sandwiched between its two halves, the three pieces being held together by rivets. A rattail tang is hidden inside a handle, which is fine if the handle material is good and the bond is permanent. The material might be plastic, epoxy-impregnated wood, or metal. The handle should be smooth and large enough that there is plenty to grip. As for the shape, if you hold a chef’s knife like a lot of professionals, then you grasp only the forward part of the handle and its particular contour doesn’t so much matter.

The part of the blade that enters the handle is called the tang. A full tang is visible all around the edges of the handle, sandwiched between its two halves, the three pieces being held together by rivets. A rattail tang is hidden inside a handle, which is fine if the handle material is good and the bond is permanent. The material might be plastic, epoxy-impregnated wood, or metal. The handle should be smooth and large enough that there is plenty to grip. As for the shape, if you hold a chef’s knife like a lot of professionals, then you grasp only the forward part of the handle and its particular contour doesn’t so much matter.

When I cook, I prefer somewhat thinner, lighter blades, whether traditionally forged or stamped out of a steel sheet. Some people mistake extra metal for a sign of quality, but a heavy knife is more tiring to use, its swollen shape more often binds in the cut, and the thicker blade takes longer to sharpen. And for the very reason that there is less metal to remove from a thinner blade, it is easier to sharpen to a steep angle: it cuts better, though it grows dull more quickly. Good French knives are generally a little lighter and thinner than their German competitors. (It’s somewhat more complicated than that. The French firm Thiers-Issard, for one, makes thinner knives for the American market than for the French one.) Global brand knives from Japan are exceptionally thin, and thus very light and sharp, but the thin butt of the blade presses uncomfortably against your middle finger, if you grip the knife partly holding onto the blade itself. Flexibility, including the extreme flexibility of a filet knife, also comes from a thin blade. The more flexible forged blades are not usually made from different steel; they’re just ground thinner.

Knives, regardless of their toughness, will eventually want care — honing on a steel, which straightens out tiny defects in the edge, and sharpening, which actually removes metal from the worn blade and re-establishes the original angle.

Everyone wants to know the name of a good electric knife-sharpener. I don’t know of one. Most remove too much metal, shortening the life of the knife, and they leave a coarse edge that for real sharpness requires a lot of honing, preferably starting with a stone and finishing with a steel — and then what’s so great about the machine? Worse, none of the machines I’ve tried allow you to sharpen the whole blade. The bolster, and even the handle of a small or narrow knife, get in the way. You can’t quite insert the entire blade, so in time the middle of the blade arcs up away from the cutting board. Plus, the machine isn’t set up to grind the bolster. Sooner or later you have to have your knives rescued by a professional.

Delay the whole problem of sharpening by protecting your knives’ sharp edges. Keep them from touching other metal, especially loose knives and utensils in a drawer or a dishwasher or dish drainer. Wash sharp knives by hand. Don’t ever leave the knives in the sink, where they may be dulled as well as cut someone. A hard plastic board is easy to clean but hard on a sharp edge; wooden is better for most things (if it picks up aromas, place it for a few hours in the sun). Before each use, hone your knives on a steel, four or five times per side; you’ll notice more improvement with staining steel than stainless. If you take care of the edges and don’t use them too often, stainless-steel knives may stay sharp for several years.

I’ve always sharpened my own knives. (All this concerns Western knives; Japanese are another world.) Least expensive is a small carborundum stone, about three-quarters of an inch by three inches, which costs a few dollars at a hardware store, but sharpening with a small stone takes time. Wet the small stone with water and, taking care not to cut your fingers, rub it in a circular motion against the blade. As you rub, the water and grit will form an abrasive paste. Usually, you rub at a 12- to 15-degree angle to the blade. (If you look closely at the edge of the blade, you may be able to determine the original angle. If you like it, copy it with the stone.) Since you sharpen both sides, that makes a “V” of 25 to 30 degrees. A steeper angle is sharper — cuts better — but it’s more vulnerable and dulls more quickly, and it takes more time to create it. A wider angle is stronger, easier to create, and dulls more slowly, but it never cuts as well. Sharpen the whole blade evenly, but concentrate on the tip if that’s the dullest part.

A two-by-eight-inch two-grit carborundum stone is much faster than the little one. Again, keep the stone wet, but move the knife rather than the stone. With larger stones like these, push the blade into the stone at 12 to 15 degrees, holding the handle in one hand and resting the fingertips of the other just short of the tip on the dull side, and making a sweep across the stone so as to grind the whole blade. (Pulling instead of pushing leaves a minute curl of metal attached to the blade, a slight disadvantage, though the steel later removes it.) Make the same number of swipes on each side, alternating every pass or two. I might make a dozen passes per side for each of the three stones, though a really dull knife requires extra time with the coarse stone (and the number of passes depends on the force you use). Check that you haven’t taken too much metal from the center of the blade by holding it at a right angle to a counter or another flat surface. If you see a sliver of light in the middle, then work more on the two ends. Reduce the bolster each time, or have a skilled professional grind it occasionally. Wipe away grit before flipping the stone to the finer side, which will remove the marks of the coarser one. To test the sharpness, draw your thumb lightly across the blade at a right angle, in one direction and then the opposite. A sharp blade will catch at your skin slightly. If both sides feel more or less alike, you’ve sharpened them equally.

Finish the edge with strokes of the steel; try to do so at the same angle you used with the stone. A steel merely completes, or later refreshes, the edge when it curls over from use; it doesn’t sharpen a dull knife. Some steels are diamond-coated to ensure they are harder than the edge they are refreshing. Most steels are magnetic. They gather any tiny bits of metal from the knife edge, so as to leave it perfectly clean and sharp.

Click here to read more from the Art of Eating on Salon, and visit artofeating.com.