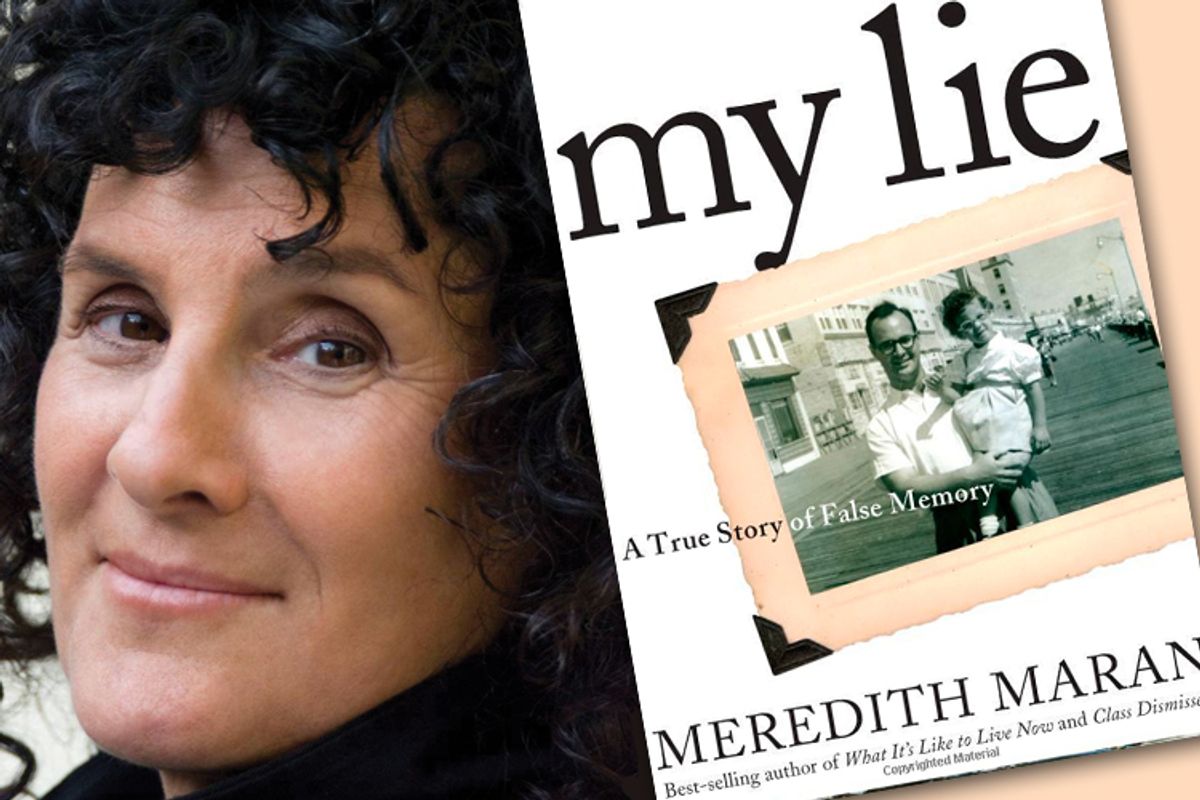

More than 20 years ago, Meredith Maran falsely accused her father of molestation. That she came to believe such a thing was possible reveals what can happen when personal turmoil meets a powerful social movement. In her book "My Lie: A True Story of False Memory" (the introduction of which is excerpted on Salon), Maran recounts the 1980s feminist-inspired campaign to expose molestation, which hit feverish levels in 1988 with the book 'The Courage to Heal." As an early reporter on the story, Maran observed family therapy sessions, interviewed molesters and steeped herself in cases where abuse clearly took place. Meanwhile, she divorced her husband and fell in love with a woman who was also an incest survivor. Maran began having nightmares about her own molestation and soon what had been a contentious relationship with her father turned into accusations of unspeakable crimes. Eventually, she came to realize the truth. She was the person who had done wrong.

Toward the end of her memoir, her father asks her, "What I really want to know is how the hell you could have thought that of me." Salon wanted to know, too. We spoke with Maran recently about how a false memory is born, what she thinks of "Courage to Heal" today, and what her story can teach us about such dangerous political narratives as the undying "Obama is Muslim" lie.

For a reader new to your story, and perhaps even the recovered memory craze of the 1980s, can you explain briefly what happened to you?

During the 1980s and 1990s, tens of thousands of Americans -- most of them middle-class, 30-something women in big cities, like me -- became convinced that they'd repressed memories of childhood sexual abuse, and then, decades later, recovered those memories in therapy.

In the years leading up to that mass panic, I was working as a feminist journalist, writing exposés of child sexual abuse, trying to convince the world that incest was more than a one-in-a-million occurrence. In the process, I convinced myself that my father had molested me. After five years of incest nightmares and incest workshops and incest therapy, I accused my father, estranging myself and my sons from him for the next eight years.

In the early 1990s the culture flipped, and so did I. Across the country, falsely accused fathers were suing their daughters' incest therapists. Falsely accused molesters were being freed from jail -- and I realized that my accusation was false. I was one of the lucky ones. My father was still alive, and he forgave me.

Why write this book now?

In 2007, I was out for a walk with someone I wasn't even that close to. She asked me if I'd ever done anything I was ashamed of and had never forgiven myself for. And without hesitation I said, yeah, when I was in my 30s I accused my father of molesting me, and then I realized it wasn't true. She stopped walking and stood still, just staring at me and she said, "The same exact thing happened to me." When I came home from that hike I started calling people I had known back then and speaking to some of the therapists I had seen during that period. With the exception of my ex-lover, every other person I talked to who had accused her father in the '80s and early '90s now believed she had been wrong. Being a journalist, you realize there's a story there.

There's an interesting arc in the book. As reports of molestation increase, you begin to believe you too were molested. And as reports of false memory increase, you realize that you were not, in fact, molested.

It's a little embarrassing for a person who's always been thought of as a critical thinker. There's a lot about writing this book and putting it out there that's embarrassing. It's not exactly the most flattering portrait. I think if it were a novel my editor would have rejected it, because the protagonist wasn't sympathetic enough. It really shocked me, I must say, to see how much influence the external had on the internal. That the most intimate emotions and relationships can be so affected by the dominant paradigm.

What surprised me was that your own discovery of molestation was more of a process than a single epiphany.

It really was a gradual thing. I don't think there ever was a time when I would have bet a hot fudge sundae on it. I remember telling my brother, "I think, maybe, this happened." And, of course, the statement of accusation is all it takes to put the wheels in motion. Either legally or in your family. One thing I've learned is the relevance of the phrase "the perfect storm." Not only for me, but for a lot of women I know who made these false accusations, it was very much a social phenomenon. Metaphorically, everything we were saying was true. But there was a confusion between a metaphor and a fact. And it was a highly relevant difference.

There were no legal implications in your case, and you never directly confronted your father. Would it have sped the process toward realizing the truth had you talked to him directly?

I was pretty terrified by my father. People ask, "What did your father say when you confronted him?" Well, I never confronted him. I withdrew from him, and I spent years sort of patching together this story and lining up the evidence.

Including a regular set of dreams that pointed to being molested. I wonder if you ascribe any meaning to those dreams now?

I felt a little stupid when I started interviewing the neuroscientists about how I could be dreaming something if it never happened. One of the doctors basically said, duh, a dream is a dream. It's not reality. It's not like something had to happen in actuality for you to dream about it, as those of us who like to dream about flying during dry sexual periods have experienced. But when I dreamed over and over about my father's hands, and all around me people were losing their heads and blaming it on incest, I said, oh, see, I'm dreaming about my father's hands. Obviously he molested me. It was just a few links that were a little extreme.

On the other end of the story, was there a moment when you could say, I have decided it did not happen?

That too went on for years, just like the process of deciding that he had. But when I stopped believing, it was a little more dramatic, during the breakup with my incest survivor lover. Over time, I had been less and less able to believe her stories, which progressed from incest with a slightly older relative to satanic ritual abuse, to the extent where I thought she was becoming defined as an incest survivor. I knew I couldn't say I don't believe her without examining my own beliefs just because her story is crazier. To my family, my story is pretty crazy too. When she left me, that was the break I needed to realize it was not true.

There is this amazing scene in the book when your father calls after you've sent him a birthday card for the first time in years and you recall that you sort of floated to the ceiling and could look down at yourself. And you hear your therapist say floating to the ceiling is what little girls do when they're molested. Can you tell me a little bit more about what happened to you that day?

That was a really good example of mind control, of brainwashing, that I had been so steeped in the symptomatology of incest survivors. How do you know it's true and what happens to little girls when they've been molested? All that stuff had gone into my head. That is a symptom of mass hysteria. I was actually transposing what I had heard from these little girls into my own psyche. When I heard my father's voice, I just went there.

Because the writing is so direct in that passage, I have to ask, what really happened?

Well, you know that feeling when you hear a voice you didn't expect to hear, that means a lot to you, and you feel weak-kneed? It was more like that. It was such an intense experience coming over my body.

At one point in the book you say, "I don't know if I'll ever be completely sure of anything again." But at the end of the book it seems clear that you have become as sure as possible that nothing happened. That's where it stands, right?

Yes. Not that I check my Amazon page or anything, but there have been some early comments that say I leave some room for doubt. That wasn't my intention.

An important catalyst for you and many women who later recanted was reading the book "The Courage to Heal." What's your opinion of that book today?

I feel mixed. The two women who put the book out are people I know. I have great respect for each of them as human beings and I think their intentions were nothing but the best. I happen to know them well enough to know that no publisher called them up and said, "If you will just make these really deceptive lists of symptoms and if you will write phrases like, 'If you think it happened, it happened,' you will become rich and famous. It's very hard now to understand the context in which that book was published. So if you take it now and say, how did they ever sell 10 copies of this book, it's such nonsense, it's easy to do. The movement that created that book doesn't exist anymore.

There's a whole body of work that came out of that time and mind-set, some of it feminist literature. Was there anything from that time that you think was useful or should it all be forgotten?

Oh no, no. In the book there's a conversation with a friend of mine who says very clearly, there were excesses, there were heartbreaks, there were tragedies in terms of our families. But at the same time, when you look at the overall impact on the world, I'm glad it happened. Kids didn't used to be protected the way they are now. Another thing, one hopes, is that a little girl who does tell, or little boy, is more likely to be believed than was true before all this happened.

You make a very interesting connection in your prologue to your story and the political landscape of today.

During the election, when people were saying Obama was a Muslim, my leftie friends would say, "What's wrong with these people? They're such idiots. How can they believe that?" And I would be watching it and thinking, that's me. I know how. Even though the intention was different, and the politics were certainly different, the fact of the matter is, I've had the experience of gradually and thoroughly coming to believe something that isn't true and acting on it. I can never look at crazy right-wingers the same way.

There's a scene in the book where you meet one of the major detractors of recovered memory, Elizabeth Loftus, and your old defenses return as you talk. It made me wonder if you feel like you betrayed your side.

I'm getting letters and responses from people in the False Memory Syndrome Foundation. Elizabeth Loftus gave me a blurb. You are so right. That is another example of conditioning. I spent years thinking the False Memory Syndrome Foundation, and Elizabeth Loftus in particular, were the devil incarnate. They were cover-uppers of this horrible crime. That's why I write about finding common ground with Elizabeth in the book, because it was so startling to me.

In the middle of the book, while you are still deeply in the mind-set of being molested, there's a notion you agree with that if one innocent man goes to prison, but it stops a hundred molesters, it's worth it. Do you still agree with that notion?

I'm fairly close to a man still in prison, and really believe he is innocent. I know how he's suffered. I know he's 80 years old and in ill health. He's spent 20 years in prison, for no reason. If every elementary school child is now taught how to protect themselves from sexual abuse -- and even more to the point, some father or preschool teacher who feels the urge to molest a child will be inhibited from doing so because they think there are guys still in jail for doing that -- but innocent people are in prison, do I have to make that choice? It is a Sophie's choice kind of thing. Would I allow an innocent man to sit in prison if it meant keeping children safe?

So would you make that choice?

I think so.

Shares