The biggest myth of the 1994 Republican takeover of Congress is that the party’s pickup of 52 House seats was somehow keyed by the “Contract With America.”

Yes, it’s true that 350 House Republicans (and GOP candidates for the House) signed the document in late September ’94 and that — for a day or two – the Washington press corps wrote and talked about it. But it’s also true that almost no actual Americans knew anything about it until the morning of Nov. 9, 1994, when they woke up to learn that a man named Newt Gingrich would be the next speaker of the House and that he was promising to honor some kind of contract with them.

The “Pledge to America” that House Republicans unveiled on Thursday is just as unknown to Americans and will remain so at least through Election Day. Even if the GOP does take back the House — an increasingly likely scenario — “the Pledge” will have nothing to do with it.

But it’s still a valuable document, because of the reaction it is generating from within the Republican Party.

Plenty of conservative commentators are dutifully praising it, or at least deeming it acceptable, but there are some upset voices too — and they are coming from the right. Red State’s Erick Erickson, for instance, blasted the House GOP’s manifesto as “full of mom tested, kid approved pablum that will make certain hearts on the right sing in solidarity. But like a diet full of sugar, it will actually do nothing but keep making Washington fatter before we crash from the sugar high.”

Contrast this with the intra-GOP response to the unveiling of “the Contract” in ’94. Back then, the only audible discontent came from the party’s moderate wing. “If I were a Democrat in a closely contested district, I’d be in church right now giving thanks,” was how then Rep. Fred Grandy, a middle-of-the-road Iowa Republican, put it.

This tells us something about how the Republican Party has evolved since 1994, and particularly how it’s evolved over the last two years.

Back in ’94, the party’s right-wing base had no memory of what it was like for Republicans to control Congress. It had been 40 years since the GOP had run the House, and some believed the Democratic majority would last forever. The base was restive, thanks to Bill Clinton’s election (which put Democrats in control of both the executive and legislative branches for the first time since the Carter years), but its anger was directed almost exclusively at Clinton and the Democrats. So it was easy for Gingrich and his team to draw up a broad document full of poll-tested platitudes and to convince just about every Republican candidate in the country — many of them far-right ideologues — to sign on.

Things have changed since then. The Gingrich Congress forced Clinton into a showdown over its balanced budget plan in late ’95, but when Clinton opted to shut down the government rather than sign off on the Medicare cuts the GOP wanted, Gingrich folded. He could read the polls as well as anyone: The shutdown was bad for the Republican Party brand. But within the conservative movement, his action stirred some resentment; this wasn’t what the “Republican Revolution” was supposed to feel like.

But it wasn’t until the Bush years, when Republicans found themselves with the White House and majorities in both congressional chambers, that a chasm really opened between the GOP base and the GOP leadership in Washington. The source of the friction was George W. Bush’s brand of big government conservatism. Republican leaders in Congress largely rubber-stamped his agenda and, at least in the 2002 and 2004 elections, the base went along without much grumbling. But when Bush’s political fortunes turned and the party suffered crushing losses in the 2006 and 2008 campaigns, the base revolted. In Barack Obama, they saw — and continue to see — the product of the failure of Republican leaders to live up to their own rhetoric.

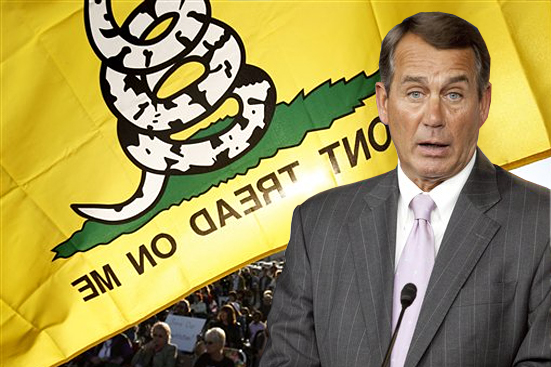

To understand this anger and where it’s coming from is to understand the Tea Party movement, which sprang up in the early days of Obama’s presidency. Its members tend to be conservative Republicans (or self-identified independents who, functionally, are conservative Republicans) who are deeply disturbed to see Democrats running Washington. In this sense, they’re no different from the conservatives of ’94, who were energized in response to the Washington monopoly Democrats then enjoyed.

The twist, though, is that their anger is also directed inward this time. Today, the GOP base knows all too well what it’s like for Republicans to enjoy a congressional majority. And they’ve learned that it matters what kind of Republicans make up that majority; if they’re not on board with the base’s right-wing ideology now, they’re almost guaranteed to see the base out once they’re in power. Thus, the energy of the GOP’s base — which is essentially synonymous with the Tea Party movement — was directed this spring and summer to taking out one wobbly, establishment-friendly Republican after another in party primaries.

Against this backdrop, right-wing skepticism about “the Pledge” makes perfect sense. The document is as vague and poll-tested as the original Contract. But the GOP base is savvier than it was in ’94, not as ready to sign on without asking questions. Will this hurt the Republicans in November? No, not in this political climate. But the reaction to “the Pledge” is yet another warning of the peril Republicans face if they actually do win back Congress this fall: Their base — the base that has dislodged one brand-name Republican after another in primaries this year — will be watching them with eagle eyes on every piece of legislation they consider.