Your body has a million ways of telling you to stop running. An unnamed muscle in your side juts against the skin like it wants out. Your knees seem to rattle and pop with every footfall, a symphony of ache. You have to go to the bathroom. It’s an emergency. And eventually all the pain and chaos swirling through your head coheres into a question: Why the hell am I doing this?

It takes a special kind of insanity to run 26 miles without being chased by the law, but each of the 47,000 runners in the New York City Marathon has a reason for it. Mine’s kind of complicated.

The walls of the Orlando, Fla., house I grew up in were neatly lined with framed medals from my father’s many marathons: Boston, Marine Corp, New York City. A few of these awards hung in the living room, just above the couch, the place I could most reliably be found back then. Well, either the couch or the kitchen.

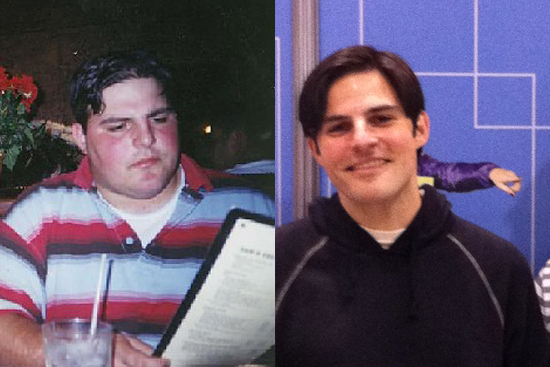

I wasn’t just a fat kid, I was the fat kid. When I was in a classroom or at Chuck E. Cheese’s, the chubby children breathed easy. Being fat defined me. It was the reason I sucked at sports and it was the reason I was great at watching movies. No other way of life seemed possible, especially not my father’s way. Losing weight might have been beyond difficult, but long-distance running was just plain dumb.

By sophomore year in college, I weighed over 300 pounds. My father had grown a little thick around the middle himself by then, but one day he showed up at my dorm 30 pounds lighter. His was a speedy, Hollywood-style weight drop — the kind that typically required a surgeon and a vacuum. But the secret he proscribed turned out to be something fairly simple — eating differently and running short distances once or twice a week. I followed my father’s lead, and the fat quickly melted off me like burger grease in a George Foreman grill (which I frequently used to make dinner).

Eventually, I discovered what most athletes already know: Results are as addictive as crack. I lost 10 pounds in a month, and nothing in the world seemed as enticing and euphoric (and likely) as losing 10 more pounds next month. Looser clothes and compliments were their own highs. More crack, please.

By the time I moved to New York, two years later, I had shed the weight, but also my identity. I wasn’t a former fat kid anymore. Letting go of that accomplishment, and the crack hit of accolades, meant some other challenge had to replace it. Perhaps it was inevitable that I set my sights on the New York City Marathon.

It took an entire year’s worth of running races to qualify. When I first started, the big day was a comfortable 19 months away, and finishing seemed a foregone conclusion. But obstacles arrived soon enough. I barely made it through a 10-mile qualifying run through Central Park, and I was daunted by the prospect of running a race nearly three times as long. I vividly remembered the toll these races took on my father, watching him tend to his battered feet after a race, scraping the dead skin off his feet with razor blades. Running a marathon is a physical feat, but it is a mental one as well, because you can talk yourself out of it at any time. Facing your dread can be trickier than a cramped muscle: What if I couldn’t finish the race because I got injured? What if it simply proved too difficult and I gave up?

But after I qualified, the dominoes began to fall. First, my brother entered the lottery to join me for what would be his third marathon. After he was accepted, my sister decided she wanted to watch us cross the finish line. Before I knew it, my entire family was booking plane tickets and pricing out hotel rooms, each one a kind of insurance policy on my finishing. Friends and co-workers offered to come cheer me on. That was it: I was locked in.

Early on Sunday morning, my brother and I set out for Staten Island, where the race began. Thousands of us were bundled up in warm, disposable garments for the hours-long lead-up to the race; on the way to the starting line, layers of clothes were discarded en masse and these soon hung from every fence post and from every tree branch in sight. It looked like a tornado had ripped through a laundromat.

Then the starter pistol fired, Sinatra’s “New York New York” came pumping through the sound — and we were off.

The sheer enormousness of the race hit me just after we passed a small army of cold people relieving themselves off the Verrazano Bridge. During the descent into Brooklyn, I got my first glimpse of the vast Fort Hamilton Parkway ahead, completely choked with bodies for miles. It was like a scene from a disaster movie, with hordes of shivering people fleeing past New York landmarks to escape something. All one needed to do to escape the marathon, though, was stop running.

As the miles zipped by, I tried not to anticipate difficult things ahead. Luckily, I was too distracted by scrappy bands doing Springsteen covers, old school boomboxes blasting Reggaeton, or groups making original Klezmer music. A couple of elderly Japanese ladies wearing wigs like pink cotton candy ran right past me, followed by a solidly built man decked out in full Gene Simmons regalia, his face covered in Kiss makeup. It took two miles of spectators yelling out “Go, Juggler!” before I realized a silver-haired man just behind me was juggling three white balls with Zen-like calm as he ran. Perhaps it was his lack of a free hand that prevented him from checking in on Foursquare at each mile-mark, which seemed to be a popular thing to do.

Two million spectators flooded the streets to watch the marathon, holding up signs and tossing out granola bars. There was rarely a moment during the race when I didn’t have the opportunity to high-five somebody. Midway through, when the strain on my body began to register on my face, I finally understood why so many people come out to cheer on runners struggling against the limits of their endurance. The onlookers become involved in that struggle, too. Sometimes I locked eyes with a total stranger and they returned my weary look with such warmth and empathy that I was deeply moved. As the Hasidim and hipsters of Williamsburg gave way to the Polish dudes and punk rockers of Greenpoint, the support never let up. It was New York at its finest.

A lot of people gave me advice while I was training. “There is no better time to run than 4:30 a.m.,” one person would say. “Drink beetroot juice every night before bed,” swore another. The most common advice I was given, though, was to just have fun. The marathon abruptly ceased to be any fun at the 20-mile mark. At that point, tunnel vision kicked in and it was all about just getting through it — preferably as soon as possible. As I ran past the next water station, the ground littered with thousands of trampled-over Gatorade cups ground into a mulchy paste, parts of my feet began to hurt that I didn’t know could hurt. My knees went rubbery. This was the part of the marathon I’d feared most.

Nothing is as seductive to a runner as the allure of ending a run early once the idea pops up. It’s like hitting the snooze button on your deepest sleep. The old, familiar urge to quit reared up, and I was flooded with the thought that this was impossible, beyond me, that I couldn’t do it. By mile 23, I officially went into panic mode and started looking for reasons to stop running.

Then I saw it. Of all the signs I’d passed during the marathon, this was the one I needed most. In giant blue letters it read, “The Pain Is Temporary, The Pride Is Forever.” When I saw that sign, my spirits lifted immediately. The entire lower half of my body may have been tenderized, but I could still do this.

Back when I was that kid on the couch, I didn’t understand what drove my father to run such long distances. Now I understood that the reason was quite simple: He did it to prove that he could. To prove — to himself, more than anyone else — that the impossible was only something in his mind. That he could do anything he set his mind to do.

As I crossed the finish line, at four fours and 40 minutes, the crowd roared. I assumed it was for me, but actually, a giant plush rhino had finished at roughly the exact same moment. When a woman placed the gold finisher’s medal around my neck, I was choking back tears.

I’d finished.

My father rushed over, brimming with congratulations. Last year he underwent surgery to replace both knees, and this was the first time he was able to give me a bear hug without wobbling a little, unsteadily.

“You’re a marathoner now,” he said. “And you’ll have that for the rest of your life.”

But I suspected my first marathon was also my last. My father’s knee surgery felt like a warning for me. But something did change at the finish line, as conclusively as when I’d lost the weight. The difference was that with the weight, I’d been running away from something, and with the marathon, I was running toward it. I can’t say what I’ll be running toward next, but whatever it is, I know one thing: that I’ll get there.

Joe Berkowitz is an assistant editor and freelance writer. His work has appeared in The Awl, McSweeney’s and Splitsider, and he blogs about pop culture at anfscu.tumblr.com.