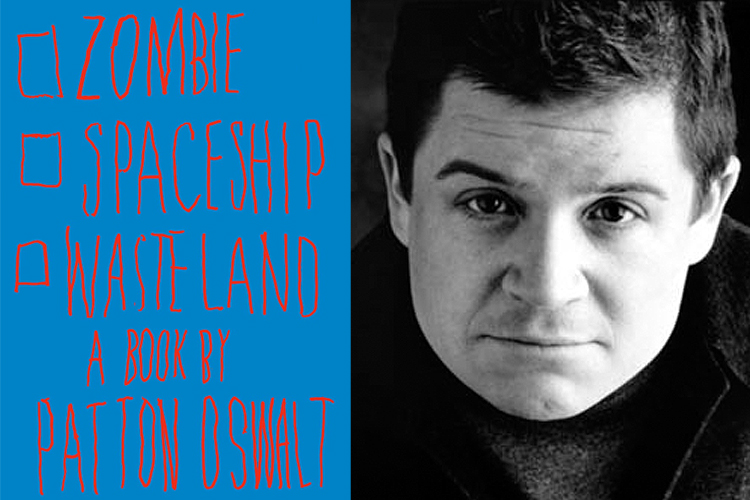

You know Patton Oswalt. As I prepared to talk to the comedian about his terrific, Gen X-era cultural memoir “Zombie, Spaceship, Wasteland,” nearly everyone I mentioned him to had an immediate, very specific response. They were, in order:

“I loved ‘Big Fan.’ “

“I wish ‘Comedians of Comedy’ would come back.”

“The voice of ‘Ratatouille‘!”

“Spence, from ‘King of Queens!”

“He was the best thing about ‘The Hangover.’ “

Actually, he never appeared in “The Hangover.” My friend had confused him with fellow “Comedians of Comedy” member and charmingly gnomish funnyman Zach Galifianakis. But it’s a testament to how ubiquitous Oswalt is that, after nearly a decade of seeing him on stage, on TV and in films, you can have a vivid recollection of one particular performance yet have a hard time pinning down who he actually is.

His new book goes a long way toward doing that. In a hilarious series of stories and vignettes (and a really wicked series of greeting cards), Oswalt captures the hyper-imaginative id of an ’80s suburban boy who grew up desperately battling boredom through the peculiar adventures of his time only to eventually outgrow them. He closes one essay about his addiction to “Dungeons & Dragons” with:

Then I went to a pool party — the first one I was skinny enough to swim at without my shirt. I made out with a girl, and the curve of her hip and the soft jut of her shoulder blades in a bikini forever trumped the imagined sensation of a sword pommel or spell book.

I spoke to Oswalt recently as he continued his comedy tour, and “Zombies” began to hit bookstores.

You have a line in your book about how writing has always taken a backseat to your “ambition to craft a perfect dick joke.”

Oh yeah, oh definitely.

So was this hard to pull off? Was it produced in fits and starts?

It was written pretty much in a sustained fashion over about nine months. I mean I was doing other things while I did it, I was doing movies and doing stand-up, but I was really focusing on doing the thing in a thematic way — even though it jumps around a lot in terms of chronology and subject matter. That is how my memory works, and I tried to sort of embrace that.

You have a chapter that spoofs classic stand-up comedy types: Blazer, the guy who goes for the cheap, ripped-from-the-headlines laughs, and another guy, “Topical” Tommy, who is really political and dour, but not very funny. I wondered reading, what type of comedian do you think you are?

God that’s a good question, because I don’t [pause] I just talk my way around an idea, and the way into the core of what I’m trying to talk about is through jokes, and through a million different punch lines hidden within the sentences rather than having the thing just end with the punch line. I’m giving a really, really garbled answer right now. I think I wrote that chapter because, whether I like it or not, all of those guys are a part of me. They all have come up, even if it was [me thinking] “I never want to be like that.”

The Blazer character is the sort of guy who comes up with, in 1988, a stunt song called “Nazi Boys,” sung to the tune of Janet Jackson’s “Nasty Boys,” about Kurt Waldheim. Blazer is hilarious because he’s exactly that wince-inducing, shticky kind of comedian, always going for the easy laughs.

Although that can be a bit of a misnomer, because, you know, laughs are not easy to get. But, you don’t want to get laughs that are just based on the things that you don’t care at all about, and that’s what I want to avoid. That’s like when people put down bands for like, you know, “they just write these hit songs.” Writing a hit song is really hard to do. But when you’re writing a hit song from just a mechanical kind of way then, yeah, that’s pretty horrible.

I read an interview where you were talking about Bill Hicks, and how sad you were that Hicks left before he could weigh in on certain current events. I wonder how consciously you try to integrate big ideas or social commentary into what you do?

It’s certainly not a premeditated thing that I’m like, I want to address this, it has to be something that affects me personally and comes out of it organically. So if I’m talking about stuff like gay marriage or the war in Iraq, it’s because it’s really affected me on a personal level and the personality of somebody that’s against it has kind of activated me on some level, but I don’t sit down and make a list, like, I’m gonna cover this topic. I’m not really conscious of it. It’s whatever is bothering me at the moment, so you know, fast food items that disgust me or people that are freaked about gay marriage that also disgust me.

But the danger is not to be Topical Tommy.

Yeah, yeah. He’s [got that problem of] having preconceptions and assumptions about the audience before he even gets to see the audience. That’s how Topical Tommy is and that’s how a lot of bad comedians are. And you know, comedians who have expectations about audiences are just as bad as audiences who have expectations about the comedians, and you can’t have either of those or you’ll get a bad show.

Your essay on your Uncle Pete, who struggled intensely with mental illness, was really moving. How influential was he on your career or your comedy?

He was more influential on my life view and the way that I kind of look at life and my place. He had a much bigger impact on that than he had on my career.

You write about how you understood the desire he felt to isolate himself, to live in his own world …

Well, you know, I’ve definitely spotted where that was in me, where those tendencies lie in me as much as I don’t want to admit I have them, but I do.

Don’t you think that’s true with a lot of creative people? That they have to resist the temptation of drawing inward and into their own private creative world?

Yeah. Or maybe what they have to learn to live with is the push and pull of wanting to be out there and be kind of extroverted, but then also needing, in order to help the work, to be introverted for a while and go live a regular life and be quiet and just observe. There has to be that balance back and forth.

And it would seem to be easier to choose and do one or the other.

But I don’t think you have to choose one or the other. You have to balance between them.

Do you think that you’ve found a balance?

I think what I’m going to do is spend my life looking for the balance, but I just don’t think I’ll ever find it. But I think the search will yield some good stuff.

You have a really funny aside, in a chapter you write about your childhood obsession with Dungeons & Dragons, mentioning that you’d revisited it later in life in what you called “perhaps the most gentle, sedentary midlife crisis ever on record.”

It happened for a few months, and it was just that thing like, I’m wallowing in nostalgia right now. And then I had a baby, and I didn’t have time to play it anymore so it didn’t really go as deep as I thought it would. It was just an amusing thing that happened for a little bit.

How old were you and how did you find people to play with?

They found me. It was a lot of my friends that started doing it and I said, hey that sounds cool, so boom — I just did it. They kind of started it without me, and I fell into it.

You were mid- or late-thirties at the time?

Yeah, late thirties I would say.

And did you think you would somehow recapture the magic?

I don’t know what I was thinking. But there wasn’t really any magic in there. It just wasn’t there, and basically mostly we would sit around and gossip. It was like a ladies sewing circle with guys rolling dice and playing wizards.