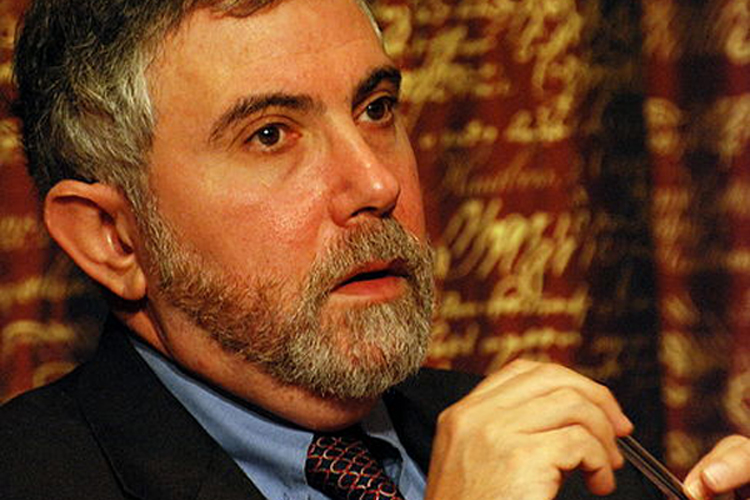

Even though it recapitulates a narrative that has been explicit and endlessly discussed since the very beginning of the Obama administration — leftist disillusionment with Obama — Benjamin Wallace-Wells’ New York Magazine profile of Paul Krugman, “What’s Left of the Left,” has been getting plenty of attention.

Maybe it’s the paradoxical tone of Wallace-Wells’ eloquently articulated elegy for liberalism — Krugman’s got a lot going for him, after all — Nobel Prize, prominent public intellectual bully pulpit, hugely trafficked blog — but somehow Wallace-Wells uses the profile to tell a story of defeat: of Obama’s failure to deliver true progressive change, and Krugman’s failure to get Washington to listen to his liberal “purism.”

For close followers of the political and economic scene, Krugman’s Obama critique is all too familiar: The stimulus should have been bigger, healthcare reform should have included a public option, the banks should have been nationalized, et cetera. Krugman staked out his position before Inauguration Day — Obama is insufficiently aggressive and ambitious — and he has stuck to it ever since. But for those on the left who are feeling a sense of outright betrayal, Krugman delivers a bit of a surprise:

Krugman has been suspicious of Obama since the beginning of the campaign, and his early doubts have remained. “It’s not so much — it’s not a values difference. I think Obama was and is committed to the welfare state.” What has always troubled him, Krugman says, is Obama’s conviction “that we can find the center and work with these people.” This seems to Krugman a deeply naive view of politics, though one that is pervasive in Washington. “There are really very, very few things, very few values issues on which both sides of our political divide agree,” he says. “You may in the end get an agreement that involves both parties but is not bipartisan in any positive sense of the word.”

The quote put me in mind of a telling moment during the conclusion of Obama’s speech on the deficit two weeks ago, when the president alluded to the partisan warfare that had plagued his term.

Of course, there are those who simply say there’s no way we can come together at all and agree on a solution to this challenge. They’ll say the politics of this city are just too broken; the choices are just too hard; the parties are just too far apart.

And then with a wry smile and downcast eyes, Obama said “And after a few years on this job, I have some sympathy for this view.”

It was a laugh line, but it was also an honest line — and just happened to be in a speech that contained the boldest articulation of Democratic values that Obama has made during his term so far. The president could have been speaking directly to Krugman. He was, in part, acknowledging Krugman’s point.

But who is really being naive here? Krugman’s position is that Obama starts too far to the right and leaves himself little negotiation room — that he reduces the politics of the possible. But you have to wonder whether Obama would have gotten any significant legislation accomplished if he had come out of the gate pushing for a much bigger stimulus, single-payer healthcare, and the nationalization of Citigroup.

Which scenario is more likely — the current Republican party buckling to Obama’s progressive vigor, or centrist Democrat senators fleeing for the hills, denying the White House 60 votes on any of its agenda items? I know where I’d lay my money down.

This is not to say that Obama couldn’t have demonstrated more leadership. It’s a fair criticism to argue that he too often allows his opponents to seize the initiative, and he hasn’t been forceful enough in articulating his own vision. That’s disappointing, but it’s not betrayal — it’s not evidence that Obama is some kind of conservative mole, destroying what remains of liberal America from within. And it should not be confused with the notion that had he been more explicitly radical he would have achieved more — that’s simply not guaranteed at all.

The two Democratic presidents who built the vast majority of the liberal welfare state we know today, Franklin Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson, operated under dramatically different political dynamics than does Obama. Their majorities were far bigger, the partisan divide wasn’t set in concrete, and — especially important — the Senate was not a place that required a super-majority for every procedural step.

It’s also worth noting that Lyndon Johnson’s civil rights accomplishments were in large part responsible for the partisan reorganization of the United States that plagues us today — the demise of the liberal northern Republican and the migration of southern Democratic conservatives to the GOP. Obama’s tragedy may be that he is by nature a conciliator and a compromiser in an era that brooks no accommodation. But true disillusionment would require confidence that a different leader could have achieved much more. I think the opposite is more likely true — a different leader could have dug us into an even deeper hole.