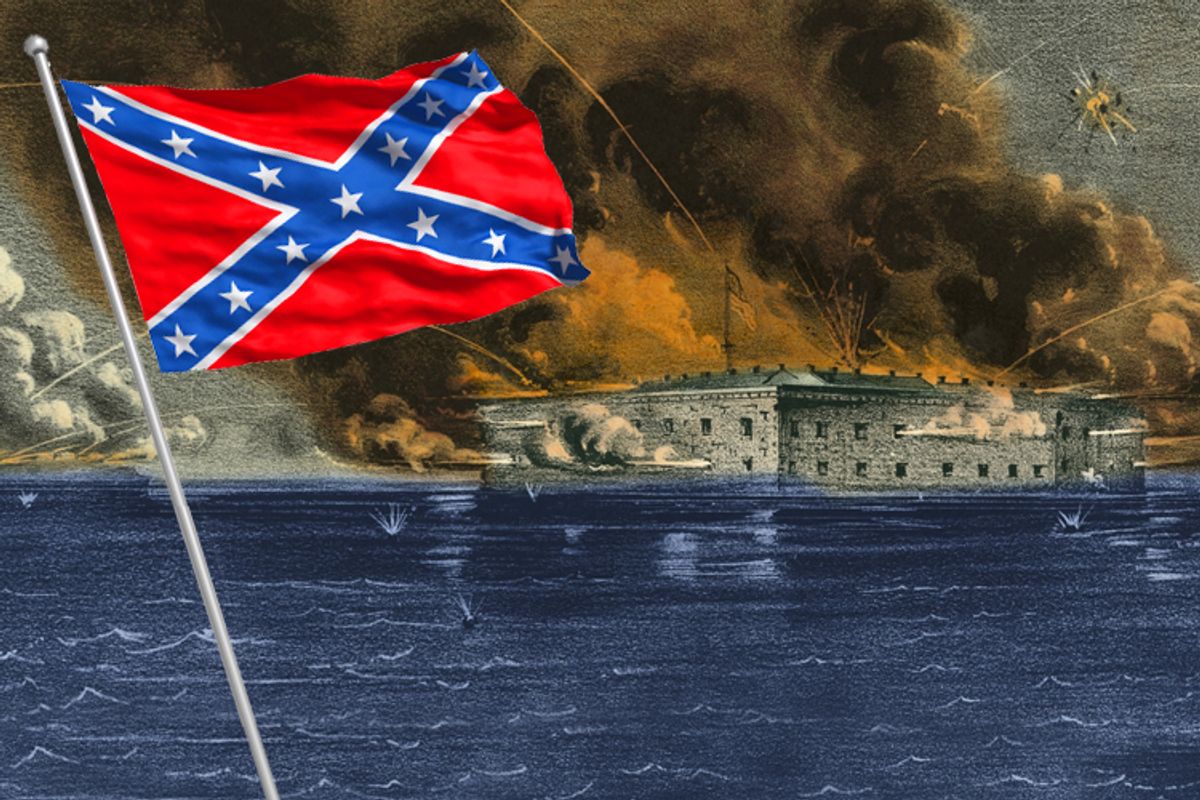

Last month, the Civil War sesquicentennial began with a bang with a "living history" event in Charleston, S.C., that commemorated the firing on Fort Sumter, the momentous act of violence that started the war.

If you’re not familiar with what "living history" means, this is a term that Civil War reenactors use to describe their hobby of dressing up in Union and Confederate uniforms and acting out battles and other significant events that occurred between 1861 and 1865. On April 12, 1861, Confederate forces fired (for real) on Fort Sumter, a military installation manned by federal troops, and continued the bombardment for more than 30 hours, when, outgunned and almost out of supplies, the Union commander, Major Robert Anderson, surrendered the fort and its garrison. It was the fall of Fort Sumter that began the Civil War, and modern reenactors pretended to do it all over again, only this time they did not use live ammunition, did not keep modern Charlestonians from getting their sleep by sustaining the thunder of cannons through the night, and presumably did no damage to the preserved stone walls of the Fort Sumter National Monument, which is located on an island in the middle of Charleston harbor.

In fact, the "living historians" at Charleston fudged the history more than a little by firing their first shot at the fort at 6:45 in the morning rather than at the very famous historical time of 4:30 a.m. Presumably, this enabled the reenactors to sleep a little later than their historical counterparts did 150 years ago. Then, when the mortar shot was finally fired to begin the reenactment, it barely sailed up 40 yards or so into the sky, although the noise it made was, according to the Charleston Post and Courier, "thunderous." But the newspaper also reported that the pyrotechnics left something to be desired: Rather than the "star shell" of a century and a half ago, the explosion seemed more like a "bottle rocket." The fireworks technician in charge of the mortar shot explained that the burst was "intentionally weak, as a safety precaution to the crowds of people on hand to witness the waterfront ceremony." So much for historical accuracy.

The promoters of this observance insisted that their event was not a "reenactment," but a moment of "living history." Although I’ve been a practicing Civil War historian for quite some time, I’ve never quite understood why reenactors dislike being called reenactors. They almost universally claim to be "living historians" or to be engaged in "living history." But I find these terms mystifying. For one thing, I think that I am a living historian; if not, someone should inform my loved ones of my passing. For another thing, "living history" makes me think of apparitions, like ghosts possessing the living and walking about historical sites in the manner of zombies, wide-eyed, with arms outstretched and flesh dangling off their faces. But if reenactors wish to be called living historians, so be it.

At any rate, the commemoration of the 150th anniversary of the Civil War is off and running (with the Union "living historians" dutifully surrendering Fort Sumter to Confederate "living historians" in a pageant held on April 14, fraught with high seriousness and furrowed brows suitable to the occasion. To a very large degree, I confess to some unease about all this playacting as we look down the road to four years of battle reenactments, fancy-dress balls (modeled on the ones portrayed in the films "The Birth of a Nation" and "Gone With the Wind"), and professions of neo-Confederate sentiments about the war having been fought over states’ rights and not slavery, as if that’s a good thing.

The sesquicentennial should be an enormous opportunity to educate the American public about the war, its causes and its consequences. The Civil War still captures the American imagination, and there is probably no more popular event in American history than the Civil War. Civil War books outnumber works about other periods of our national history (despite the fact that the American Revolution was actually the single most important event in our country’s history), Civil War national parks outnumber other historical parks from a single time period, and Civil War reenactors and buffs by far outnumber other enthusiasts who immerse themselves in the details of, say, the French and Indian War or even World War II. Still, for all this interest, many Americans still possess little understanding of the Civil War and its outcome. The sesquicentennial might help to remedy this knowledge gap by raising public awareness of the war in all its many dimensions, revealing local aspects of the war to many who might not know that their communities were involved in fighting the war or supporting the war effort, and spreading a broad public understanding of what the war meant to the people who experienced it and to subsequent generations of Americans who live, even 150 years later, in its very long shadow.

But the thought of being deluged with everything about the Civil War over the next four years leaves me with a distinct feeling of dread, if not outright exhaustion. For one thing, I already "live" in the Civil War era on practically a daily basis. It is my job to read and write about the war, to teach my students about it, to speak to scholarly and community groups about it, and to learn as much about it, day to day, month to month, year to year, as I possibly can. The fact is, I’m already immersed in the Civil War -- so much so that I often feel like I need a vacation from the 19th century, just to stay in touch with my family, my friends and the world in which I live. Other Civil War academics have admitted to me their similar feelings: For those of us who "do" Civil War history, it is possible sometimes to o.d. on the Civil War. When that happens, I purposely take a vacation to some place unhistorical in nature or importance, drag along a suitcase filled with pulp fiction, detective novels and unread magazines from our coffee table, and find a quiet, shady place to forget about the Civil War. Inevitably, these "rehab" experiences fail miserably, and I usually end up with my thoughts drifting to some aspect of the war as Hercule Poirot continues to gather clues or as Thomas Frank says something truly brilliant in his Harper’s "Easy Chair" column. Predictably, I begin scribbling notes about my next writing project on slips of paper, napkins and those little, otherwise useless pads you find next to the telephone in hotel rooms. Being a Civil War historian means living in the 19th century, whether you like it or not, and it’s damned difficult to jump back and forth between centuries.

Which is why, in at least one respect, I find the unfolding Civil War sesquicentennial daunting. As more and more people become involved in the war’s commemoration, I fear not only immersion but inundation. How much more Civil War can I deal with in my in life? How much more can I sink below its depths before it drowns me? How much more can anyone stand?

Civil War reenactors and buffs seem to have a far greater tolerance level than I do. They live and breathe the war readily, without hesitation, and with a passion that veers close to a religious experience or even sexual arousal. I have a passion for my work, especially my writing and my teaching, but enough’s enough. I lack the hobbyist’s obsession with the war, its players (great and small), and its minutia (which is endless). My job requires me to be an expert about the war, a position I do believe I’ve attained, but I can’t bring myself to devote the entirety of my life to it -- and I certainly (unlike some of my academic cohort) have no interest in donning a uniform, firing a Springfield musket, or participating in a battle reenactment under a blazing sun or a dripping sky.

In fact, the entire idea of commemorating the Civil War strikes me as perverse, including bloodless battle reenactments. Why would anyone want to replicate one of the worst episodes in American history? Why would anyone want to pretend to be fighting a battle that resulted in lost and smashed lives on the field and utter grief among the soldiers’ loved ones back home? Is there any uplifting message to be derived from such playacting? What’s more, these "reenactments" are contrived and orchestrated. In order to avoid everyone falling down and playing dead during these battle plays (or no one falling down at all), reenactors decide by lottery in advance who will clutch their heart and tumble to the ground as though they’ve been hit; some of the fallen inevitably try to lie still if they are supposed to be dead, others try to simulate wounded men by crawling away from the scene of "carnage" (if you pay attention, you’ll see that they’re actually crawling to the nearest shade tree), while still others sometimes try stealthily to get their hat over their faces to avoid sunburn.

No one, of course, uses live ammunition, except for one French reenactor who did so during the 135th anniversary reenactment of Gettysburg, where he slightly wounded an American reenactor in the stomach; all charges (assault with a deadly weapon, etc.) were later dropped against the Frenchman, who was speedily deprived of his ammunition and put on a fast plane to Paris. When cannons are fired at reenactments, they do not produce explosions or rip through the advancing ranks of the enemy, since they are in essence firing only blanks -- that is, powder charges without projectiles. Nevertheless, these battle reenactments usually produce a good number of real casualties, which turn out to be mostly burns from overheated muskets and artillery pieces, heat prostration and the occasional heart attack among overweight baby boomers who are trying, despite their huge girths and hardened arteries, to portray fit, young soldiers.

More to the point, though, is the strange desire to impersonate soldiers of the Civil War by pretending to fight a battle. In the first place, these pretend battles look and sound nothing like the real thing, although reenactors have convinced the public (and themselves) that they do. In the second place, these theatricals lose every bit of authenticity the moment the demonstration draws to a close and the faux dead and wounded on the field rise up in a mass resurrection resembling the Rapture, which is usually accompanied by the applause of the onlookers (who, by the way, have paid a hefty admission price to see grown men shoot at one another with the adult equivalent of cap guns). The crowd usually finds these phony battles truly entertaining, perhaps in the same way that "professional" wrestling has its devoted fans. Nevertheless, entertainment -- no matter how authentic the reproduction buttons and firearms might be -- is not history. Interestingly, a good number of reenactors actually have been in real combat, having served (and gotten shot at) in Vietnam, the Persian Gulf, Somalia, Iraq and Afghanistan. Perhaps these veterans find it difficult to leave their military identities behind. But it can’t be easy for them to reconcile the actual horrors of battle with the sanitized "combat" of a reenactment.

The Civil War as entertainment was something that particularly troubled Bruce Catton, the dean of Civil War historians during of the 1950s and 1960s. At the start of the Civil War Centennial, Catton warned:

"We are in serious danger of taking the most significant anniversary in American history and using it as a means of giving ourselves a bright and colorful holiday. How the Civil War soldier fought his battles is no doubt worth examining, but infinitely more important is a consideration of why he fought and what he accomplished. Lay on the sentiment, the romance, and the dramatic appeal heavily enough, and we shall presently forget that the war was fought by real living men who were deeply moved by thoughts and emotions of overwhelming urgency."

If Fort Sumter and every one of the war’s significant events are to be reenacted in the sesquicentennial, will the bill of fare include the massacre of African American troops at Fort Pillow (1864)? Or the seizure of free African-Americans who were dragged against their will into slavery when Robert E. Lee’s Confederate army retreated back to Virginia following the battle of Gettysburg? Or the explosion of the S.S. Sultana’s boilers (April 1865), when an estimated 1,800 Union soldiers -- some of whom were recently released prisoners of war who had already suffered countless miseries at the infamous Andersonville camp in Georgia -- were killed on the Mississippi River near Memphis? Where should the paroxysmal "heritage" festivals begin and end? And how accurate will any of these celebrations of the past really be?

I’ve never attended a reenactment where the Confederate encampments are replete with compliant African-Americans portraying the slaves who actually accompanied their masters -- officers and enlisted men -- on the march. No doubt it’s hard to find modern African-Americans willing enough to play slaves alongside modern white Americans playing Confederate soldiers; in the actual Civil War, though, slaves often did all the hard work and toting, sometimes carrying their master’s musket, blanket roll, cooking utensils and the like. In the Union army, contraband (fugitive) slaves were sometimes put to use in equally menial ways. It’s telling, of course, that African-Americans don’t often attend Civil War battle reenactments. In fact, National Park Service statistics reveal that African-Americans rarely even visit Civil War battlefields. For good reason, modern blacks are a little sensitive about slavery and anything that seems to suggest -- as reenactments most assuredly do -- that the Civil War was all about battles, that each side fought with equal courage and grand moral purpose, and that the war had nothing to do with slavery or emancipation.

It also boggles the mind how over the next four years the nation is supposed to go about commemorating the war’s immense brutality. How, quite frankly, is one expected to commemorate the contents of the following letter, written by a Virginia soldier to his mother in 1864?

"I wrote you a few days ago after having received the sad news of my poor, dear brother’s death. I hope you received the letters. You do not know, dear Mother, how sad I am, and how deeply I feel the loss of him we all loved so dearly ... The longer I live the more convinced am I that there is no real happiness in this world without the hope of heaven. I have tried for the last six months to live a better life, and I hope that God will aid me in the effort, and that when it may please him to take me, that I will have nothing to fear. You must remember, Mother, that you have five children left yet to comfort you and compare your condition with that of other Mothers who have had all [their sons] taken. Tell Lucy that she must remember she has two little children to live for. I know her affliction is too deep for utterance, and deeply do I feel for her. She and her little ones are dear, very dear, to me. Would that I could do a father’s part by them."

Perhaps the impossibility of doing justice to this soldier’s feelings is precisely why Congress has repeatedly refused to authorize a national commission for the commemoration of the sesquicentennial. More likely, the partisanship that has created deadlock in Congress over almost everything else is the real political reason behind the lack of a federal commission, but without an agency to oversee the anniversary, the whole observance already seems to have fizzled. Of course, Congress is not about to tackle tough issues, and any official commemoration of the Civil War would only emphasize how hypocritical, how morally (and financially) bankrupt, our republic has become in the New Gilded Age of the 21st century. The Civil War, in other words, is too difficult for Congress to manage. It’s too messy. It involves taking stock of who we are and where we have come from. It means facing up to hard truths and unkept promises. So Congress, in typical fashion, has ducked the sesquicentennial.

If so, it’s not entirely without cause -- beyond, that is, the nervous fear of confronting hard historical truths. The Civil War Centennial 50 years ago was a notable disaster. The national commissions created by Congress suffered from mismanagement in its early days, until several prominent historians stepped in and saved it from self-immolation, but meanwhile the civil rights movement made the commemoration of Civil War battles look and sound profoundly hollow. One hundred years had passed since the war had been fought, presumably granting full civil rights to African-Americans and ensuring those rights in the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments; and yet, blacks were still fighting to secure those rights and yearning to be treated with the dignity they deserved as Americans and as human beings. As African-Americans pushed their civil rights movement forward in the '60s, they were vehemently opposed by states rights segregationists who resurrected the Confederate battle flag as a symbol of white supremacy. As Robert J. Cook, who has written a history of the centennial that should give all Americans pause as they stumble their way into the sesquicentennial, insightfully concludes: "If the Civil War centennial tells us anything, it is that seemingly entrenched historical memories are not always a match for the onrush of time." Regrettably, as minorities continue to struggle for equality in our land of the free and the home of the brave, the lost cause of the Confederacy continues to dominate public conceptions of what the Civil War means to us today. Moonlight and magnolias define the essence of the Civil War for most Americans. And public celebrations dreamily embrace the romance of a war that should, by all rights, repel us and horrify us and send shivers of fright down our spines. The commemoration of the sesquicentennial deserves to be more funereal than mirthful, more disconsolate than cheery.

One prominent Civil War historian, Allen C. Guelzo of Gettysburg College, sees the sesquicentennial as pitting so many different interests against one another -- academic historians, popular historians, public historians, reenactors, community organizers and the general public -- that he believes we might as well "call the whole thing off." Needless to say, that’s not possible, since the sesquicentennial will happen whether we want it to or not, and the lack of a federal commission to oversee and coordinate the commemoration won’t stop anyone from doing so, as the recent festivities in Charleston have loudly made plain. If one takes the rather lackluster Lincoln bicentennial into account, I’m tempted to agree with Guelzo -- a Lincoln scholar who, by the way, offered no such cautionary remarks about that overblown and extremely dull commemoration of the 200th birthday of the 16th president that dragged on for two excruciating years. Personally, though, I don’t think we need to call off the Civil War sesquicentennial; there are ways of commemorating it without necessarily indulging in battle reenactments or costume balls, hoop skirts and all.

One might begin by reading Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. I’m serious. It contains only 272 words, but it spelled out for the American people -- in Lincoln’s own time and in ours -- the entire meaning of the Civil War. Actually it offers something for everybody in this second decade of the 21st century. If you’re a Tea Party right-winger, you’ll want to do some arm pumping during the opening lines of the address that refer to the Founding Fathers and the Declaration of Independence. Any conservative has to take heart with Lincoln’s references to life and liberty and happiness. Liberals will react to the address with more melancholic feelings for the good old days, since the speech refers to a government "of the people, by the people, for the people," rather than our present reality of a government of the corporations, by the lobbyists and for the rich.

Still, Lincoln had a great deal to say in his little speech, which was delivered to dedicate the Soldiers’ National Cemetery at Gettysburg on Nov. 19, 1863, and he said it so well, in timeless prose. Eloquently and in plain words, Lincoln held forth a promise that the war would not be fought in vain. He saw a new America emerging out of the old, a country more dedicated to its most cherished ideals, a nation reborn out of the fire and ashes of war. His words elevated the significance of the Civil War beyond a fight simply to restore the Union. Confronting the deadly reality of the battle -- the grisly remains that still, in some cases, awaited reburial on the day of the cemetery’s dedication -- Lincoln honored the Union men "who here gave their lives" for the sake of their country; by doing so, the president helped Americans, then and now, focus on the ideal of the warrior’s sacrifice rather than on the reality of the soldier’s suffering. The ground at Gettysburg, as Lincoln said, had been duly consecrated, as if gods, rather than ordinary soldiers, had spilled their blood there. His heroic image of the dead did not, at the time, diminish the awful reality of the battle and the war. As Lincoln’s speech gained popularity after his death, his words were increasingly understood as articulating the deeper meaning of the war, which, in his opinion, involved not only the preservation of the Union, but the initiation of a new era of equality and freedom.

One might successfully argue that the "new birth of freedom" Lincoln hoped for never came about, although most Civil War historians -- including James M. McPherson, the present dean of Civil War scholars -- insist that it did. He and the other experts who agree with him are right only in the sense that freedom for whites expanded and soared in the postwar era and well into the 20th and 21st centuries. Otherwise, it took a century, in the face of strong white resistance, for blacks and other minorities -- including immigrants of every stripe -- to win even a modicum of the rights and the fruits of freedom that the 620,000 lives expended in the Civil War were supposed to have given them. Nevertheless, the place to begin if one wants to understand the true, deeper meanings of the war -- and how we as Americans have failed to keep its promises or bring about Lincoln’s hope for a new birth of freedom -- is to read the Gettysburg Address. You might also want to glance at the Declaration of Independence to see how the two documents fit hand-in-glove.

All in all, it seems to me that the best way to commemorate the Civil War is to do so by leaving the war to the dead rather than the living -- to acknowledge in a solemn manner how absolutely harrowing and heartrending the war actually was and to observe its anniversary with gestures that are private, quiet and gentle. While pudgy Civil War reenactors pretend to relive history, perhaps the soldiers who fought the real battles -- and who gave their lives or shed their blood in them -- should be honored with true respect and a hushed gravitas. How can a somber (and sober) commemoration be achieved?

Read a book about the Civil War, particularly any of a wide assortment of fine books about how soldiers endured the conflict’s many hardships and how the experience of combat altered their view of themselves and their world. I can recommend several that reveal in stunning detail how soldiers of the Union and Confederacy saw themselves and understood their respective causes; a good number of these works also reveal the soldiers’ day-to-day lives, in camp and on the battlefield -- their dedication to ideology and cause, their courage and their fears, their humor and sadness, their fortitude and despair, their comradery and loneliness. Start with Bell I. Wiley’s two older (but not outdated) books: "The Life of Johnny Reb" (1943) and "The Life of Billy Yank" (1952). For a literary treat, as well as a narrative account of how Union soldiers in the Army of the Potomac endured the miseries of repeated defeats and inept generals, move on to Bruce Catton’s trilogy, "Mr. Lincoln’s Army" (1951), "Glory Road" (1952), and "A Stillness at Appomattox" (1953). Catton, who won the Pulitzer Prize for "Stillness" in 1954, maintains a tightly focused perspective on the ordinary soldiers of the Army of the Potomac. The reader gets to follow those soldiers down long dirt lanes, dusty or muddy, as they experience their distressing defeats and their greatest victories.

Several more recent books also offer valuable, and sometimes startling, insights into soldier life during the Civil War: Reid Mitchell's "Civil War Soldiers" (1988) and "The Vacant Chair: The Northern Soldier Leaves Home" (1993); Gerald F. Linderman's "Embattled Courage: The Experience of Combat in the Civil War" (1989); Earl J. Hess' "The Union Soldier in Battle: Enduring the Ordeal of Combat" (1997); James M. McPherson's "For Cause and Comrades: Why Men Fought in the Civil War" (1997); and Chandra Manning's "What This Cruel War Was Over: Soldiers, Slavery, and the Civil War" (2007). None of these works is a ponderous scholarly tome, although each one is based on solid scholarship, innovative research and engaging prose. I’ve also made my own contribution to the literature on Civil War soldiers in my book, "Twilight at Little Round Top" (2005), which examines the fight for a crucial hill at Gettysburg primarily through the eyes of six ordinary soldiers, three Union and three Confederate.

A flood of additional Civil War books will come pouring off the presses during the sesquicentennial, but caveat emptor -- most of them will claim to be new and original on their dust jackets, but the greatest number of them will be derivative and redundant. For a list of what I consider to be the best 12 books ever written on the Civil War (since, that is, 1950 or so), check out my earlier Salon essay. If you don’t know where to get started reading about the Civil War, I recommend Louis P. Masur’s fresh and amazingly brief (for all the ground it covers), "The Civil War: A Concise History" (2011), which contains a superb bibliography that you can use as a guide to further reading on a variety of Civil War subjects, including general works that treat the war in more detail. When all else fails, the Internet offers oceans of information about the Civil War. Some websites, of course, are more worthy or reliable than others, but it won’t take long to learn how to find the good ones and navigate away from the schlock.

Fiction may be more to your liking, and if so, there are several novels about the Civil War that historians either revere or hate. Most scholars love Michael Shaara’s "The Killer Angels" (1974), which tells the story of Gettysburg with terse prose and vivid characters; it later became the basis for the movie "Gettysburg" (1993), an uneven film that has a few moments of brilliance in it. The novels of Shaara’s son Jeff are not as beloved as his father’s book, which won the Pulitzer Prize; the younger Shaara wrote a prequel and a sequel to his father’s book, and in both instances the son’s extraordinary lack of talent as a writer is embarrassingly revealed (nevertheless, his books are uncritically adored by Civil War buffs). Another novel that’s generally despised by scholars, although not by me, is Gore Vidal’s "Lincoln" (1984), an epic (and, at times, almost whimsical) portrait of the president during the war years that blends myth and history artfully together in such a way that leaves the reader wondering if the real Lincoln can ever truly be known -- a very real question that every Lincoln biographer must wrestle with. Those same Lincoln biographers, however, generally have condemned the novel for all its fictionalization of Honest Abe’s presidency -- a criticism that Vidal answered by pointing out that his book was indeed a novel, which I think gives him the last word. Charles Frazier’s "Cold Mountain" (1997) shot to the top of the bestseller lists and won rave reviews when it was first published, but the reader must trek through miles and miles of the author’s minute descriptions of blossoming flora and blue mountains and pastel skies, as his protagonist must do, to reach the story’s very predictable conclusion; this novel, too, was made into a tolerable movie that was filmed in Romania of all places and starred Nicole Kidman (an Australian) and Jude Law (a Brit). Go figure. And then, of course, there is "Gone With The Wind," the novel (1936) and the movie (1939). The movie is better than the novel, which also won a Pulitzer, although both are well worth the effort. Personally, I consider Mark Twain’s "Adventures of Huckleberry Finn" (1884) the greatest novel written about the Civil War (although it takes place before the war broke out) and the greatest American novel of all time. Period.

If, however, you are "not really into reading," as one of my students so candidly informed me after admitting that she had not read any of the eight assigned books for my Civil War course (she got an F), you can mark the sesquicentennial in other tranquil and reverential ways. It should not be necessary to point out that the Civil War was tragic, not romantic, but the romanticism is what dominates public conceptions of the war. Allen Nevins, a brilliant historian whose work is now mostly ignored by younger scholars, once attempted to emphasize the war’s enormous tragedy by making this profoundly powerful point: "We can say that the multitude of Civil War dead represent hundreds of thousands of homes, and hundreds of thousands of families, that might have been, and never were. They represent millions of people who might have been part of our population today and are not. We have lost the books they might have written, the scientific discoveries they might have made, the inventions they might have perfected. Such a loss defies measurement." Nevins wrote those words in 1961, and it seems unlikely that his admonition, or anything I could add to it, will impress Civil War enthusiasts to abandon the romantic myths of the war in favor of a stark realism that lays out, without any varnish, how Americans suffered and sacrificed as they killed one another in droves.

Even some academic historians shrink from accepting the hellishness of the Civil War. One scholar, Mark E. Neely Jr., complains that vital aspects of the war have become hidden by what he believes has been an overemphasis on the conflict’s destructiveness, what he condemns among his fellow experts as "a cult of violence." He argues, in fact, that the Civil War was, comparatively speaking, no more violent or destructive than other wars, which may or may not be so, but his contention that the war was somehow less violent than historians have claimed flies in the face of the fact that 620,000 Americans died in the four years between 1861 and 1865. Historians haven’t exaggerated the war’s human toll; if anything, they still have not dealt effectively with the sensationalized romance -- promulgated in part by the Civil War generation itself -- that smothers our comprehension of the contest between North and South as an excessive expression of an American tradition of violence (on this point, see my earlier essay, "Our permanent culture of political violence").

It’s the Civil War dead, not "living historians," who deserve our attention during the sesquicentennial. If you live in the eastern two-thirds of the country, from Nebraska to Maine and from Texas to Florida, chances are there’s a Civil War monument in a nearby town or city honoring the community’s volunteers who fought and died for their cause. A few years ago, just by chance, I came across a handsome soldiers’ monument in the little Massachusetts community of Marion, not too far from Plymouth. It stands boldly on a small patch of land at an intersection. What struck me, though, and the only reason I noticed it all, was that the lawn around the tall memorial had been carefully manicured and lovely clumps of marigolds had been planted around the stone base. Obviously someone -- perhaps a community group, a senior citizens’ center, or a Boy Scout troop -- cared deeply for the monument. I was impressed -- and deeply touched. Someone in the community recognized the monument’s importance and respected the contribution the Marion soldiers had made during the War of the Rebellion, enough, in fact, to honor them with small gestures: a mowed lawn, some flowering plants and a polished, shining statue. Standing in the monument’s shadow, it occurred to me that someone, whoever it was, understood the true meaning of the Civil War and remembered eloquently and poignantly what the community’s brave young men -- now long gone from this earth -- had given so selflessly a century and a half ago. The groomed lawn was one thing, but the pretty marigolds, a fitting substitute for forget-me-nots, spoke volumes.

If there is a monument to Civil War soldiers in your community, you might think about leaving a bouquet of flowers or a wreath at its base. Or if the local memorial has been overgrown and is in disrepair, organize a community group to spruce it up. Commemorate Memorial Day by remembering not only the service to our country of all military personnel, including those killed in combat, but do so in a way that fits the origin of the holiday -- in both the North and the South -- as Decoration Day, a single day specifically dedicated to the memory of the Civil War’s fallen soldiers. If there is a national cemetery near you, there’s a good chance it contains the remains of Union soldiers, even if you live in the western states, such as California, Washington and Oregon. In the Southern states, there are numerous cemeteries either dedicated exclusively to the Confederate dead or that contain special sections marked off for Southern combat casualties or veterans who died after the war. Even in the Northern states, there are Confederate cemeteries located near former Union prisoner-of-war camps, such as Elmira, N.Y., or Point Lookout, Md.. You might want to visit these cemeteries and remember the dead by strolling through, reading the names, and leaving a flower or a small flag on a grave or headstone.

Civil War museums abound in the eastern United States, more so in the South than the North, but often state and local historical societies display artifacts or tell the story of how your community participated in the war. If the federal government can manage to survive this spring without shutting down, you might visit a Civil War battlefield administered by the National Park Service, which consistently does a fine job of educating visitors not only about the battle fought there, but also about the causes and consequences of that particular battle and of the entire war. In many Southern states, there are also worthy Civil War sites operated as state parks.

If you have an ancestor who served during the war, you might want to track down his grave and pay your respects. Don’t forget that civilian men and women served as doctors and nurses on both sides; they deserve to be honored and remembered as much as the soldiers who fought in the ranks. If you want to find out if one of your ancestors shouldered a musket for the Blue or Gray, the Internet is the place to start your genealogical quest. Several private and commercial sites will help you find your way and discover whether or not your kin helped to determine the outcome of the war. Perhaps you even have old letters or diaries written by a Civil War forbear. If so, make photocopies of them and then explore the possibility of donating the originals to a historical society, library, museum or even the Library of Congress, so that historians can benefit by using them in their research. You may not want to let such documents out of your family. If that’s the case, think about taking one of the letters and getting it professionally framed so you can hang it in your house or office and point it out to relatives and friends, proudly telling them: "Here’s a letter written by my great-great-grandfather during the Civil War."

Yet none of these silent tributes really get to the heart of the Civil War. Some historians talk about the Civil War’s "unfinished business," as if the conflict involved a checklist that no one got around to completing. Actually the war changed everything in the United States: how Americans thought about themselves and their country; how work and industry could be organized, just like the huge armies that tramped from battle to battle; how the nation would henceforth define citizenship and civil rights; how equality would be heralded and, sadly, curtailed (both at the same time); how the federal government steadily grew in size and scope but adopted laissez-faire policies, especially when if came to regulating business or neglecting the downtrodden; how people would relate to one another -- more circumspect, less innocently than in the old days before the war; and even how people would speak to one another using new, crisp, declarative slang words and a rugged American language, captured so perfectly in the writings of Mark Twain, that resembled soldier talk and the realism of war. What the war did not change -- not permanently, anyway -- were white attitudes toward African-Americans and other minorities. Nor have those attitudes changed all that much in our own time, despite some of the very real advances that have marked race relations since Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and other tangible victories of the civil rights movement.

In 1961, at the start of the Civil War Centennial, Walker Percy, the talented Mississippi novelist, observed that "the country has still not made up its mind what to do about the Negro." Fifty years later, while a black man occupies the Oval Office, we still haven’t made up our mind as to what we should do about African-Americans and every other minority that inhabits this nation. White racial fears are hidden behind "birther" accusations, draconian immigration proposals and political attacks on federal entitlement programs; some white Americans even cry out that they want to take their country back.

The Civil War sesquicentennial can give them only one answer: You may try to get it back by pretending to fire on Fort Sumter, as the Civil War reenactors did in Charleston two weeks ago. Or you may try to get it back by joining the Tea Party and working to turn back the hands of time to the glory days you imagine as having once existed. But you can’t get your country back. You lost it 150 years ago. Ever since then, whether you like it or not, the steady march of the United States has been toward the higher ground, the greater purpose, of democracy and equality. And while that march has sometimes been stalled or even derailed, while it has been barricaded, hosed down and even sold out, nothing, nothing, has ever succeeded in keeping it permanently from moving forward. Perhaps, in the end, that’s the real legacy and the true significance of the Civil War.

Shares