“The New Generation” (“Molodniak”), a short story by Alexander Solzhenitsyn, recently appeared for the first time in English translation on the American Scholar website. Written in 1993, the story was first printed two years later in the Russian journal Novyi Mir.

The 1990s were a strange time for Solzhenitsyn. In 1991, he published the last volume of “The Red Wheel,” his 5,000-page novel about the history of the Russian Revolution — the fruit of 18 years of toil in the woods of Vermont. It was not overwhelmingly well-received. In 1994, Solzhenitsyn returned to Russia. If you remember one thing about his return, it’s that they briefly gave him his own talk show, and that the host was likened to “a combination of Charlie Rose and Moses.” Solzhenitsyn eventually abandoned the pretense of inviting guests and simply talked the whole time himself, mostly about the corruption and spiritual decline of Russia. The show was cancelled after a year.

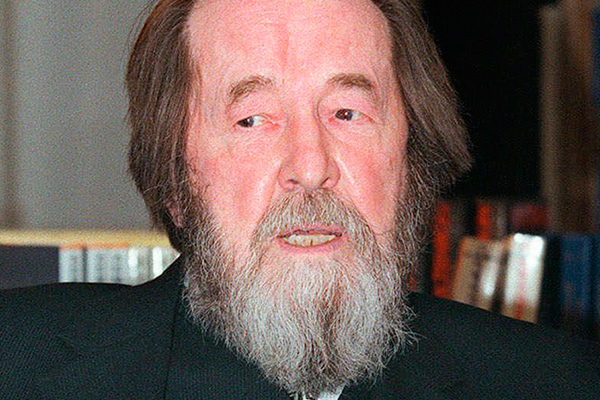

Solzhenitsyn is one of those writers who seem always to have been old. (Having spent his youth in the war and the camps, he was already 43 when he published his first book, “A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich.”) With his Old Believer beard and his intolerance of rock music, he wasn’t, for most of his career, a man of his time. His contemporaries were forever likening him to cranky old guys, from Jeremiah to Tolstoy. The image of Solzhenitsyn on 1990s Russian TV, competing with Mexican soap operas, is arresting for this reason. It has the vertiginous quality of certain historical outcomes, at once inevitable and inconceivable.

“The New Generation” captures this same elusive pathos of being out of joint with time. It’s one of Solzhenitsyn’s “binary tales,” a technique he adopted late in his career, juxtaposing two separate but related stories to convey a moral point. It’s a good form for him. “The New Generation” isn’t the most subtle work of literature, but it’s surprisingly gentle, with no harangues or negative characters. It’s a story about kindness, its fruits and limitations.

The two main characters are an engineering professor and his least capable student: a tin worker forced into the university by a mass education program. The worker is totally lost in class; clearly, the preparation — an “intensive two-year course” — wasn’t enough. This is an obvious metaphor for the plight of the Soviet Union in 1926, when the story opens. As one bystander observes at a political rally: “It’s easy to say, ‘Achieve a whole decade of development in two years,’ but working at that pace might well kill you.”

A quibble here about the English translation, by Kenneth Lantz: that Russian phrase (“… no ot takogo tempa mozgi rvutsia“) is more literally translated as “…but working at that pace will rip up your brain.” Earlier, the tin worker observes that the engineering class — a class in “strength of materials” — is “breaking [his] brain”; Lantz’s translation, “it’s buggered up [his] brain,” sounds to me needlessly figurative.

Basically, the worker’s new life is making his brain explode. That’s what happens to people when they’re plunked into the future — and when such a fate befalls an entire nation at once, the potential for destruction is enormous. The engineer sees this danger, but tries not to believe it: “Three generations of the intelligentsia could not have been mistaken about how to give the people access to culture and liberate their energies,” he reasons. “Of course, not everyone has what it takes to cope with this surge ahead, this leap forward.”

Some people, he realizes, will be broken — but not him, right? Not the engineers — the very people responsible for building the new world? These questions are answered in the second part of the story, which reunites the teacher and student under very different circumstances in 1931.

To me, the most moving scene in “The New Generation” is a conversation between the engineer and his eighth-grade daughter, whom he is trying to persuade to join the Komsomol (the Communist Union of Youth).

“You know,” he suggested gently, and indeed, he fully believed it himself, “this new generation of young people really does have something, some truth that we can’t fully understand. They certainly must have something… You simply can’t avoid swimming along in this stream, my dear, or you might well let the whole Epoch slip past, as they say.”

The conversation takes place in 1926 — the same year that Victor Shklovsky published “Third Factory,” his study of literary “unfreedom”: “The time cannot be mistaken; the time cannot have wronged me,” Shklovsky writes. “It’s wrong to say: ‘The whole squad is out of step except for one ensign.’ I want to speak with my time, to understand its voice.”

How do you write for your time, to your time, in a voice it can understand? How do you swim with the stream? What if it breaks your head against a rock? Hadn’t you better break it with a rock, first? You won’t find the answers in “The New Generation,” but the question is elegantly stated.